2/N

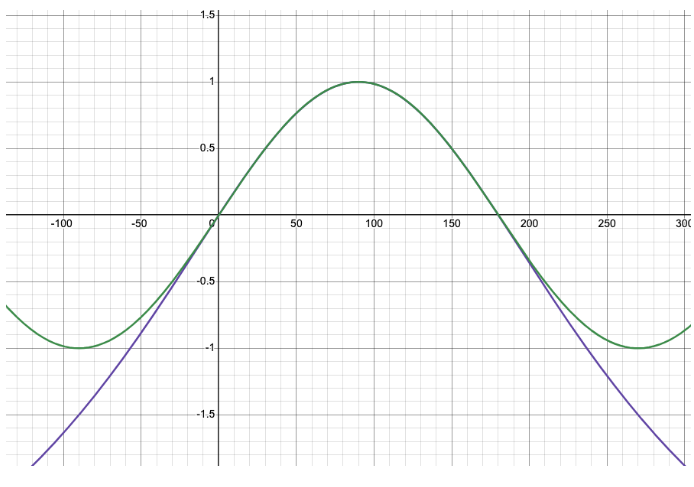

The sine function, with its smooth, undulating wave, is among the most profound and versatile tools in mathematics, woven into the fabric of the universe and touching fields as diverse as astronomy, machine learning, structural engineering, number theory, and music.

The sine function, with its smooth, undulating wave, is among the most profound and versatile tools in mathematics, woven into the fabric of the universe and touching fields as diverse as astronomy, machine learning, structural engineering, number theory, and music.

5/N

In geometry, a half chord is a segment that connects a point on a circle to the midpoint of a chord of the circle. Essentially, it is half the length of a full chord, extending from one endpoint of the chord to its midpoint.

In geometry, a half chord is a segment that connects a point on a circle to the midpoint of a chord of the circle. Essentially, it is half the length of a full chord, extending from one endpoint of the chord to its midpoint.

8/N

In ancient Indian trigonometry, "rsine" refers to the "radius sine" or "radii sine". It represents the sine of an angle multiplied by the radius of the circle

In ancient Indian trigonometry, "rsine" refers to the "radius sine" or "radii sine". It represents the sine of an angle multiplied by the radius of the circle

9/N

This concept of rsine was used in ancient India when trigonometric functions were often tabulated as values multiplied by the radius, since the sine function itself is a ratio.

This concept of rsine was used in ancient India when trigonometric functions were often tabulated as values multiplied by the radius, since the sine function itself is a ratio.

10/N

Instead of using the concept of the unit circle, these values were typically expressed with respect to a circle of a certain radius.

Instead of using the concept of the unit circle, these values were typically expressed with respect to a circle of a certain radius.

11/N

In modern trigonometry, we typically assume a unit circle (where the radius is 1), so the sine function directly gives us the rsine, and the term "rsine" is no longer in common use.

In modern trigonometry, we typically assume a unit circle (where the radius is 1), so the sine function directly gives us the rsine, and the term "rsine" is no longer in common use.

12/N

Often, an astronomer in ancient India would have to make calculations with the half-chord of double the angle for a circle of radius R

Often, an astronomer in ancient India would have to make calculations with the half-chord of double the angle for a circle of radius R

13/N

One of the first Indian contributions to trigonometry was to tabulate values as not a table of chords, but a table of half-chords. These “half-chords” are known today as sines

One of the first Indian contributions to trigonometry was to tabulate values as not a table of chords, but a table of half-chords. These “half-chords” are known today as sines

14/N

The Sanskrit word Jyā means a bow-string and thus the chord of an arc. The arc of a circle is called Chapa in Sanskrit. Generally, Jyā means the straight line of one point to another in a circumference of a circle which is known as ‘chord’ in English.

The Sanskrit word Jyā means a bow-string and thus the chord of an arc. The arc of a circle is called Chapa in Sanskrit. Generally, Jyā means the straight line of one point to another in a circumference of a circle which is known as ‘chord’ in English.

15/N

The Sanskrit term “koti” encompasses meanings such as “the curved end of a bow” or “the end or extremity in general.” In the realm of Trigonometry, it evolved to represent “the complement of an arc of 90 ̊”.

The Sanskrit term “koti” encompasses meanings such as “the curved end of a bow” or “the end or extremity in general.” In the realm of Trigonometry, it evolved to represent “the complement of an arc of 90 ̊”.

16/N

Utkrama refers to a concept of reversal, outward movement, or surpassing. Therefore, the term utkramajya essentially translates to “reverse sine.”

Utkrama refers to a concept of reversal, outward movement, or surpassing. Therefore, the term utkramajya essentially translates to “reverse sine.”

17/N

This function earns its name in contrast to krama-jya because its tabulated values are obtained by subtracting elements from the radius in reverse order from the tabulated values of the latter.

This function earns its name in contrast to krama-jya because its tabulated values are obtained by subtracting elements from the radius in reverse order from the tabulated values of the latter.

18/N

A circle is commonly divided into four parts called quadrants by two perpendicular lines, typically the east-to-west line and the north-to-south line. These quadrants are further categorized into odd (अयुग्म or विसम) and even (युग्म or सम).

A circle is commonly divided into four parts called quadrants by two perpendicular lines, typically the east-to-west line and the north-to-south line. These quadrants are further categorized into odd (अयुग्म or विसम) and even (युग्म or सम).

20/N

Ancient Indian astronomers faced the daunting challenge of accurately predicting the movements of celestial bodies across the vast expanse of the sky.

Ancient Indian astronomers faced the daunting challenge of accurately predicting the movements of celestial bodies across the vast expanse of the sky.

21/N

These calculations were crucial not only for understanding the cosmos but also for practical purposes like calendar-making, timing religious rituals, and navigation.

These calculations were crucial not only for understanding the cosmos but also for practical purposes like calendar-making, timing religious rituals, and navigation.

22/N

The complexity of these astronomical problems, particularly those involving the elliptical orbits of planets, the varying length of days, and the prediction of solar and lunar eclipses, demanded a sophisticated mathematical framework.

The complexity of these astronomical problems, particularly those involving the elliptical orbits of planets, the varying length of days, and the prediction of solar and lunar eclipses, demanded a sophisticated mathematical framework.

23/N

The sine function, in particular, became central to calculating the positions of planets, the timing of eclipses, and the determination of day lengths, providing the precision needed to align their astronomical predictions with observed reality.

The sine function, in particular, became central to calculating the positions of planets, the timing of eclipses, and the determination of day lengths, providing the precision needed to align their astronomical predictions with observed reality.

24/N

Thus, to ancient Indians trigonometry was not just a theoretical pursuit but a practical invention driven by the need to unravel the mysteries of the astronomical problems and bring order to both cosmic and earthly cycles.

Thus, to ancient Indians trigonometry was not just a theoretical pursuit but a practical invention driven by the need to unravel the mysteries of the astronomical problems and bring order to both cosmic and earthly cycles.

25/N

The opening verse of Bhāskara's discussion on trigonometry in the Siddhāntaśiromaṇi gives an idea how important computation of sine function was to ancient Indians

The opening verse of Bhāskara's discussion on trigonometry in the Siddhāntaśiromaṇi gives an idea how important computation of sine function was to ancient Indians

28/N

To highlight the significance of trigonometry in ancient Indian astronomy, here's a brief selection of the astronomical problems tackled in the Surya Siddhanta, Aryabhatiya, and Mahābhāskarīya.

To highlight the significance of trigonometry in ancient Indian astronomy, here's a brief selection of the astronomical problems tackled in the Surya Siddhanta, Aryabhatiya, and Mahābhāskarīya.

29/N

The Surya Siddhanta uses trigonometric functions to calculate the mean and true positions of planets. The equation of center, which accounts for the eccentricity of the orbits, is determined using trigonometric methods to correct the mean positions

The Surya Siddhanta uses trigonometric functions to calculate the mean and true positions of planets. The equation of center, which accounts for the eccentricity of the orbits, is determined using trigonometric methods to correct the mean positions

30/N

In Surya Siddhanta, trigonometry is also used to predict solar and lunar eclipses by calculating the angular distances between the Sun, Moon, and Earth.

In Surya Siddhanta, trigonometry is also used to predict solar and lunar eclipses by calculating the angular distances between the Sun, Moon, and Earth.

31/N

The Surya Siddhanta employs trigonometric methods to convert between different celestial coordinate systems, such as from ecliptic to equatorial coordinates. It also accounts for the precession of the equinoxes using trigonometric calculations

The Surya Siddhanta employs trigonometric methods to convert between different celestial coordinate systems, such as from ecliptic to equatorial coordinates. It also accounts for the precession of the equinoxes using trigonometric calculations

32/N

Aryabhata employs trigonometric methods to predict the occurrence of solar and lunar eclipses by calculating the angular distances between the Sun, Moon, and Earth.

Aryabhata employs trigonometric methods to predict the occurrence of solar and lunar eclipses by calculating the angular distances between the Sun, Moon, and Earth.

33/N

Trigonometry is also used in Aryabhatiya to determine the size and shape of the Earth's shadow (umbra and penumbra) during lunar eclipses and the Moon's shadow during solar eclipses.

Trigonometry is also used in Aryabhatiya to determine the size and shape of the Earth's shadow (umbra and penumbra) during lunar eclipses and the Moon's shadow during solar eclipses.

34/N

Aryabhata applies trigonometric functions to calculate how the length of the day varies throughout the year. This variation is due to the tilt of the Earth’s axis and its elliptical orbit around the Sun, and trigonometry helps in modeling these changes.

Aryabhata applies trigonometric functions to calculate how the length of the day varies throughout the year. This variation is due to the tilt of the Earth’s axis and its elliptical orbit around the Sun, and trigonometry helps in modeling these changes.

35/N

Aryabhata also calculates the Sun’s declination (its angular distance north or south of the celestial equator) using trigonometric functions, which is essential for understanding seasonal changes.

Aryabhata also calculates the Sun’s declination (its angular distance north or south of the celestial equator) using trigonometric functions, which is essential for understanding seasonal changes.

36/N

Aryabhata uses trigonometry to solve problems involving spherical triangles, which are formed by great circles on the celestial sphere. This is crucial for determining positions of celestial bodies in the sky, and their altitude and azimuth from a given location on Earth.

Aryabhata uses trigonometry to solve problems involving spherical triangles, which are formed by great circles on the celestial sphere. This is crucial for determining positions of celestial bodies in the sky, and their altitude and azimuth from a given location on Earth.

37/N

Bhaskara uses trigonometric functions in Mahābhāskarīya to calculate the mean and true positions of planets, correcting for orbital eccentricities using the equation of center. This allows for more accurate predictions of planetary positions over time.

Bhaskara uses trigonometric functions in Mahābhāskarīya to calculate the mean and true positions of planets, correcting for orbital eccentricities using the equation of center. This allows for more accurate predictions of planetary positions over time.

38/N

Trigonometric functions are used by Bhaskara to calculate how the length of the day varies over the course of the year. Bhaskara's calculations take into account the Earth's axial tilt and its elliptical orbit around the Sun.

Trigonometric functions are used by Bhaskara to calculate how the length of the day varies over the course of the year. Bhaskara's calculations take into account the Earth's axial tilt and its elliptical orbit around the Sun.

39/N

In Mahābhāskarīya, trigonometry is employed to estimate the distances of celestial bodies from Earth, based on their apparent angular sizes and positions. This involves calculating the parallax and applying trigonometric functions to determine the actual distances.

In Mahābhāskarīya, trigonometry is employed to estimate the distances of celestial bodies from Earth, based on their apparent angular sizes and positions. This involves calculating the parallax and applying trigonometric functions to determine the actual distances.

41/N

Khalif Abbasid Al Mansoor ( 712 CE - 775 CE) was the second Abbasid caliph. He is known for founding the 'Round City' of Madinat al-Salam, which was to become the core of imperial Baghdad.

Khalif Abbasid Al Mansoor ( 712 CE - 775 CE) was the second Abbasid caliph. He is known for founding the 'Round City' of Madinat al-Salam, which was to become the core of imperial Baghdad.

42/N

Khalif Abbasid Al Mansoor invited a scholar named Kanka from Ujjain, India in 770 CE to teach the Arabs the Hindu system of arithmetic and astronomy.

Khalif Abbasid Al Mansoor invited a scholar named Kanka from Ujjain, India in 770 CE to teach the Arabs the Hindu system of arithmetic and astronomy.

43/N

The primary text that Kanka (Hindu scholar) was using to teach the Arabs was the book Brāhma-sphuṭa-siddhānta by Brahmagupta (composed no later than 628 CE).

The primary text that Kanka (Hindu scholar) was using to teach the Arabs was the book Brāhma-sphuṭa-siddhānta by Brahmagupta (composed no later than 628 CE).

44/N

By the order of the Khalif, Brāhma-sphuṭa-siddhānta was translated by Al-Fazari into Arabic and was named “Sind Hind” or “Hind Sind”. Later, as abridged version of that work was published by Mummad Bin Musa Al-Khwarzimi ( 825 CE)

By the order of the Khalif, Brāhma-sphuṭa-siddhānta was translated by Al-Fazari into Arabic and was named “Sind Hind” or “Hind Sind”. Later, as abridged version of that work was published by Mummad Bin Musa Al-Khwarzimi ( 825 CE)

45/N

Sachau in the preface of Al-beruni’s “India”, pointed out that the Arabs learnt their astronomy from Brahmagupta’s Brāhma-sphuṭa-siddhānta before they came to know about Ptolemy.

Sachau in the preface of Al-beruni’s “India”, pointed out that the Arabs learnt their astronomy from Brahmagupta’s Brāhma-sphuṭa-siddhānta before they came to know about Ptolemy.

46/N

When the Sanskrit word "Jyā" was introduced to the Arab world, it was transliterated as "jiba," its phonetic equivalent. However, due to the common practice of omitting vowels in Arabic, "jiba" came to be written as "jyb" (جيب).

When the Sanskrit word "Jyā" was introduced to the Arab world, it was transliterated as "jiba," its phonetic equivalent. However, due to the common practice of omitting vowels in Arabic, "jiba" came to be written as "jyb" (جيب).

47/N

In the 12th century, one of the key Arabic trigonometric works translated into Latin was "Kitāb al-Zīj" (The Book of Astronomical Tables), authored by Persian scholar Al-Battani. His work significantly influenced the development of trigonometry in the Latin-speaking world.

In the 12th century, one of the key Arabic trigonometric works translated into Latin was "Kitāb al-Zīj" (The Book of Astronomical Tables), authored by Persian scholar Al-Battani. His work significantly influenced the development of trigonometry in the Latin-speaking world.

48/N

The Latin book translated from al-Battani's work is known as "De Motu Stellarum" (On the Motion of the Stars). The translation is often attributed to Plato of Tivoli (Plato Tiburtinus)

The Latin book translated from al-Battani's work is known as "De Motu Stellarum" (On the Motion of the Stars). The translation is often attributed to Plato of Tivoli (Plato Tiburtinus)

49/N

The Latin translators mistakenly interpreted the word "jyb" as "jaib" because they shared the same spelling (جيب). In Arabic, "jaib" which means a fold in a garment or a pocket)

The Latin translators mistakenly interpreted the word "jyb" as "jaib" because they shared the same spelling (جيب). In Arabic, "jaib" which means a fold in a garment or a pocket)

50/N

As a result, the Latin translators translated "jaib" into its Latin equivalent, "sinus," which means a gulf, curve, or hollow. Over time, "sinus" evolved into the modern English word "sine"

As a result, the Latin translators translated "jaib" into its Latin equivalent, "sinus," which means a gulf, curve, or hollow. Over time, "sinus" evolved into the modern English word "sine"

52/N

Surya Siddhanta combines profound mathematical insights with astronomical observations. It introduced advanced concepts such as spherical geometry, trigonometric identities, accurate models for predicting eclipses, and sophisticated algorithms for planetary motions.

Surya Siddhanta combines profound mathematical insights with astronomical observations. It introduced advanced concepts such as spherical geometry, trigonometric identities, accurate models for predicting eclipses, and sophisticated algorithms for planetary motions.

53/N

The dating of Surya Siddhanta is complex. Some scholars date the surviving version of the text to between the 4th and 5th centuries CE.

The dating of Surya Siddhanta is complex. Some scholars date the surviving version of the text to between the 4th and 5th centuries CE.

54/N

The traditional Indian thought process is that Surya Siddhanta is a much older text which has been updated several times over a period of time to update astronomical observations.

The traditional Indian thought process is that Surya Siddhanta is a much older text which has been updated several times over a period of time to update astronomical observations.

55/N

One of the pieces of evidence that the Surya Siddhanta was a living text comes from the 10th-century scholar Bhattotpala, who cited and quoted ten verses from a version of the text that are absent in any surviving manuscripts.

One of the pieces of evidence that the Surya Siddhanta was a living text comes from the 10th-century scholar Bhattotpala, who cited and quoted ten verses from a version of the text that are absent in any surviving manuscripts.

56/N

Anil Narayanan's research article, "Dating the Surya Siddhanta Using Computational Simulation of Proper Motions and Ecliptic Variations," investigates the age of the Surya Siddhanta through software simulations.

Anil Narayanan's research article, "Dating the Surya Siddhanta Using Computational Simulation of Proper Motions and Ecliptic Variations," investigates the age of the Surya Siddhanta through software simulations.

57/N

The study employs computational simulations of stellar proper motions, ecliptic obliquity, and ecliptic node variations to date the text. The results suggest that the Sūrya Siddhānta has been revised multiple times over its history.

The study employs computational simulations of stellar proper motions, ecliptic obliquity, and ecliptic node variations to date the text. The results suggest that the Sūrya Siddhānta has been revised multiple times over its history.

58/N

Narayanan's findings indicate that the original Surya Siddhanta is like a very old text - earlier than 7800 BC. The most recent update to the text was done in 580 AD.

Narayanan's findings indicate that the original Surya Siddhanta is like a very old text - earlier than 7800 BC. The most recent update to the text was done in 580 AD.

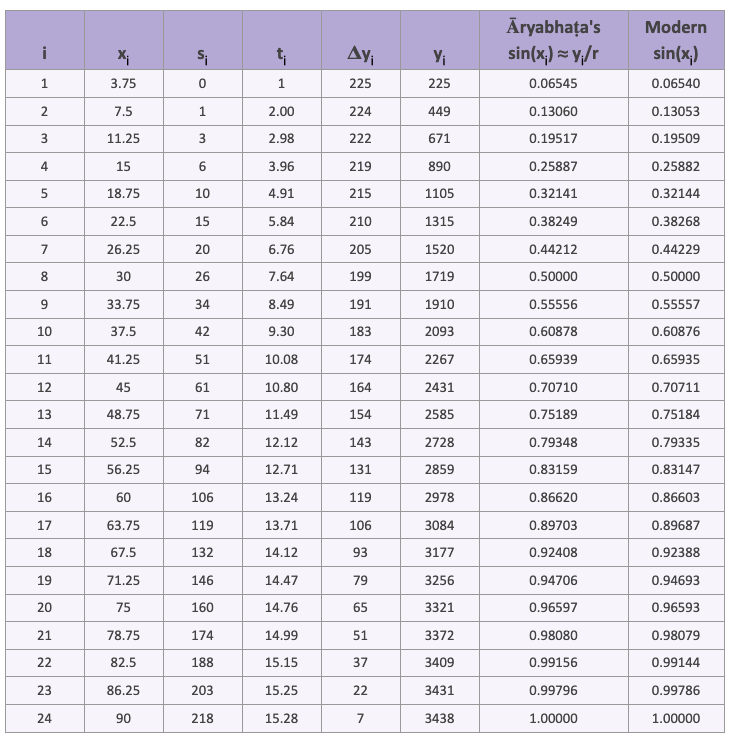

59/N

Chapter 2 of the Surya Siddhanta outlines methods for calculating sine values. It divides a quadrant of a circle with a radius of 3438 into 24 equal segments, corresponding to the sine values detailed in the table.

Chapter 2 of the Surya Siddhanta outlines methods for calculating sine values. It divides a quadrant of a circle with a radius of 3438 into 24 equal segments, corresponding to the sine values detailed in the table.

60/N

In contemporary terms, each of these segments represents an angle of 3.75°.

In contemporary terms, each of these segments represents an angle of 3.75°.

68/N

The Āryabhaṭīyaṃ is a profound Sanskrit astronomical treatise composed of 121 verses, each dense with meaning.

The Āryabhaṭīyaṃ is a profound Sanskrit astronomical treatise composed of 121 verses, each dense with meaning.

69/N

The text is divided into four sections: the Gitikapada (13 verses), the Ganitapada (33 verses dedicated to mathematics), the Kalkriyapada (25 verses), and the Golapada (50 verses focused on astronomy, the most renowned of the four).

The text is divided into four sections: the Gitikapada (13 verses), the Ganitapada (33 verses dedicated to mathematics), the Kalkriyapada (25 verses), and the Golapada (50 verses focused on astronomy, the most renowned of the four).

70/N

For the first time in the annals of mathematics, Āryabhaṭa defines the sine function with a poetic elegance that transcends the boundaries of science.

For the first time in the annals of mathematics, Āryabhaṭa defines the sine function with a poetic elegance that transcends the boundaries of science.

73/N

As both mathematician and poet, Āryabhaṭa composed the Āryabhaṭīyaṃ in verses, meticulously metered and grammatically precise stanzas, blending the precision of mathematics with the rhythm of poetry.

As both mathematician and poet, Āryabhaṭa composed the Āryabhaṭīyaṃ in verses, meticulously metered and grammatically precise stanzas, blending the precision of mathematics with the rhythm of poetry.

74/N

The Āryabhaṭīyaṃ was crafted in the rhythmic Arya meter (छन्द), where the first, second, third, and fourth pādas contain 12, 18, 12, and 15 mātrās respectively.

The Āryabhaṭīyaṃ was crafted in the rhythmic Arya meter (छन्द), where the first, second, third, and fourth pādas contain 12, 18, 12, and 15 mātrās respectively.

75/N

This precise structure can be seen in the following example from Kālidāsa's renowned play, Abhijñānaśākuntalam (c. 400 CE):

आ परितोषाद्विदुषां न साधु मन्ये प्रयोगविज्ञानम्

बलवदपि शिक्षितानामात्मन्यप्रत्ययं चेतः

This precise structure can be seen in the following example from Kālidāsa's renowned play, Abhijñānaśākuntalam (c. 400 CE):

आ परितोषाद्विदुषां न साधु मन्ये प्रयोगविज्ञानम्

बलवदपि शिक्षितानामात्मन्यप्रत्ययं चेतः

76/N

Nearly every prominent Indian mathematician has engaged with the Āryabhaṭīyaṃ, frequently through formal commentaries known as Bhashyas.

Nearly every prominent Indian mathematician has engaged with the Āryabhaṭīyaṃ, frequently through formal commentaries known as Bhashyas.

77/N

The list of ancient Indian mathematicians who composed commentaries on Āryabhaṭīyaṃ includes Bhaskara I (629 CE), Suryadeva (1191 CE), Parameshvara (1400 CE) & Nilakantha Somayaji (1500 CE)

The list of ancient Indian mathematicians who composed commentaries on Āryabhaṭīyaṃ includes Bhaskara I (629 CE), Suryadeva (1191 CE), Parameshvara (1400 CE) & Nilakantha Somayaji (1500 CE)

78/N

As a key figure in the Kerala school, Nilakantha continued the groundbreaking tradition initiated by Madhava (1350–1420 CE), who laid the foundations for the calculus of trigonometric functions.

As a key figure in the Kerala school, Nilakantha continued the groundbreaking tradition initiated by Madhava (1350–1420 CE), who laid the foundations for the calculus of trigonometric functions.

79/N

Let’s focus back on Āryabhaṭīyaṃ. Among Ganitapada's verses, two stand out for addressing the solution to the linear Diophantine equation, which has rightly been acknowledged.

Let’s focus back on Āryabhaṭīyaṃ. Among Ganitapada's verses, two stand out for addressing the solution to the linear Diophantine equation, which has rightly been acknowledged.

80/N

However, our emphasis will be on the trigonometry within the Ganitapada

However, our emphasis will be on the trigonometry within the Ganitapada

81/N

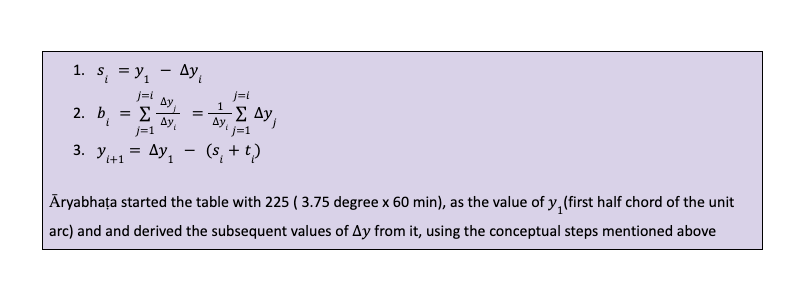

Āryabhaṭa provides two methods for computation of sine values. We are going to take a look at both of them

Āryabhaṭa provides two methods for computation of sine values. We are going to take a look at both of them

83/N

Translation of the above verse:

One must divide a quarter of the circumference of a circle into triangles and rectangles. Thus will be obtained the required Jyās of arcs of equal lengths, when the radius of the circle is given.

Translation of the above verse:

One must divide a quarter of the circumference of a circle into triangles and rectangles. Thus will be obtained the required Jyās of arcs of equal lengths, when the radius of the circle is given.

87/N

Āryabhaṭa used 3438 as the radius, which he derived by considering the circumference of the circle as 360 (degrees) x 60 (minutes) = 21600 (minutes)

Āryabhaṭa used 3438 as the radius, which he derived by considering the circumference of the circle as 360 (degrees) x 60 (minutes) = 21600 (minutes)

88/N

In the 10th verse of Ganitapada of Āryabhaṭīyaṃ, Āryabhaṭa employed the value of π as 62832/20000, which equates to 3.1416.

In the 10th verse of Ganitapada of Āryabhaṭīyaṃ, Āryabhaṭa employed the value of π as 62832/20000, which equates to 3.1416.

95/N

In the first chapter of this work, Vrahamihira gives summaries of five Siddhantas, namely Vasistha Siddhanta, Paitamaha Siddhanta, Paulisa Siddhanta, Rokama Siddhanta & Surya Siddhanta

In the first chapter of this work, Vrahamihira gives summaries of five Siddhantas, namely Vasistha Siddhanta, Paitamaha Siddhanta, Paulisa Siddhanta, Rokama Siddhanta & Surya Siddhanta

96/N

Varahamihira provided two rules for constructing a Table of Jyā, the first of which was already mentioned by Arayabhata earlier.

Varahamihira provided two rules for constructing a Table of Jyā, the first of which was already mentioned by Arayabhata earlier.

100/N

Notice how two famous trigonometric identities are mentioned in this recipe by Varahamihira.

Notice how two famous trigonometric identities are mentioned in this recipe by Varahamihira.

104/N

Another brilliant ancient Indian mathematician Bhāskara-I (no later than 600 CE) provided an entirely different method for computing sine of any arc.

Another brilliant ancient Indian mathematician Bhāskara-I (no later than 600 CE) provided an entirely different method for computing sine of any arc.

109/N

Also, notice how Bhaskara’s approximation satisfies two most important properties of the sine function

* Symmetric about θ= 90

* Concave over the range 0 <= θ <= 180

Also, notice how Bhaskara’s approximation satisfies two most important properties of the sine function

* Symmetric about θ= 90

* Concave over the range 0 <= θ <= 180

110/N

It is simply a stroke of genius that Bhaskara’s recipe provides more than 99% accuracy for the range of 0 <= θ <= 180

It is simply a stroke of genius that Bhaskara’s recipe provides more than 99% accuracy for the range of 0 <= θ <= 180

111/N

Many subsequent Indian mathematicians who dealt with the subject of finding sine without using tabular sines have given the rule more or less equivalent to that of Bhāskara I

Many subsequent Indian mathematicians who dealt with the subject of finding sine without using tabular sines have given the rule more or less equivalent to that of Bhāskara I

122/N

Madhava created a groundbreaking sine table that stands as a testament to his genius. This table meticulously lists the Jyās or Rsines for 24 angles, spanning from 3.75° to 90° in precise 3.75° increments.

Madhava created a groundbreaking sine table that stands as a testament to his genius. This table meticulously lists the Jyās or Rsines for 24 angles, spanning from 3.75° to 90° in precise 3.75° increments.

123/N

The Rsine values, calculated by multiplying the sine by a selected radius and expressed as integers, demonstrate a level of accuracy that echoes Aryabhata's earlier work, where R is defined as 21600 ÷ 2π ≈ 3438

The Rsine values, calculated by multiplying the sine by a selected radius and expressed as integers, demonstrate a level of accuracy that echoes Aryabhata's earlier work, where R is defined as 21600 ÷ 2π ≈ 3438

124/N

The table is artfully encoded in the Sanskrit alphabet by Madhava through the Katapayadi system, transforming its entries into the lyrical verses of a poem.

The table is artfully encoded in the Sanskrit alphabet by Madhava through the Katapayadi system, transforming its entries into the lyrical verses of a poem.

125/N

The Katapayadi system is an ancient Indian mnemonic technique used for encoding numbers into syllables or letters, primarily for remembering large numbers. It's a traditional method in Indian mathematics and can be found in ancient texts like the Kāśyapa's Tattvakaumudī.

The Katapayadi system is an ancient Indian mnemonic technique used for encoding numbers into syllables or letters, primarily for remembering large numbers. It's a traditional method in Indian mathematics and can be found in ancient texts like the Kāśyapa's Tattvakaumudī.

126/N

Vowels are often used as placeholders or to complete the words. For example, specific consonants correspond to digits from 0 to 9, and by combining these consonants, one can encode numbers into words or phrases.

Vowels are often used as placeholders or to complete the words. For example, specific consonants correspond to digits from 0 to 9, and by combining these consonants, one can encode numbers into words or phrases.

127/N

Though Madhava's original work containing this table remains lost to time, its legacy endures.

Though Madhava's original work containing this table remains lost to time, its legacy endures.

128/N

The table finds its echoes in the Aryabhatiyabhashya by Nilakantha Somayaji (1444–1544) and in the Yuktidipika/Laghuvivrti commentary on Tantrasamgraha by Sankara Variar (circa 1500–1560)

The table finds its echoes in the Aryabhatiyabhashya by Nilakantha Somayaji (1444–1544) and in the Yuktidipika/Laghuvivrti commentary on Tantrasamgraha by Sankara Variar (circa 1500–1560)

130/N

The last verse translates to “These are the great R-sines as said by Madhava, comprising arcminutes, seconds and thirds. Subtracting from each the previous will give the R-sine-differences.”

The last verse translates to “These are the great R-sines as said by Madhava, comprising arcminutes, seconds and thirds. Subtracting from each the previous will give the R-sine-differences.”

134/N

Madhava also gave us the brilliant Madhava sine series, one of the three infinite series expansions for the sine, cosine, and arctangent functions.

Madhava also gave us the brilliant Madhava sine series, one of the three infinite series expansions for the sine, cosine, and arctangent functions.

135/N

It took Europeans more than 250 years to independently rediscover these series.

It took Europeans more than 250 years to independently rediscover these series.

136/N

The series for sine and cosine were reintroduced by Isaac Newton in 1669, while the series for arctangent, known as Gregory's series, was rediscovered by James Gregory in 1671 and Gottfried Leibniz in 1673.

The series for sine and cosine were reintroduced by Isaac Newton in 1669, while the series for arctangent, known as Gregory's series, was rediscovered by James Gregory in 1671 and Gottfried Leibniz in 1673.

141/N

In the beginning of the 10th chapter, Ptolemy claims to arrive at the calculation by simple theorems, as few in number as possible.

In the beginning of the 10th chapter, Ptolemy claims to arrive at the calculation by simple theorems, as few in number as possible.

142/N

However it is important to point out that Ptolemy did not mention whether his method of calculation is his own or is borrowed from somewhere else.

However it is important to point out that Ptolemy did not mention whether his method of calculation is his own or is borrowed from somewhere else.

144/N

Here I would like to draw your attention to how biased some Western scholars have been in their approach to analyze brilliant and original works by Indian mathematicians and astronomers.

Here I would like to draw your attention to how biased some Western scholars have been in their approach to analyze brilliant and original works by Indian mathematicians and astronomers.

145/N

An example is Bernhard Friedrich Thibaut, a German mathematician who suggested that the Table of Jyā offered in Panchasiddhantika is derived from the Table of Chords given by Ptolemy - simply because the two tables look similar.

An example is Bernhard Friedrich Thibaut, a German mathematician who suggested that the Table of Jyā offered in Panchasiddhantika is derived from the Table of Chords given by Ptolemy - simply because the two tables look similar.

146/N

Thibaut argued that the Indian Table of Jyā was possibly derived from Ptolemy’s Table of Chords by dividing Ptolemy’s arcs by 2 and retaining his values for the chords.

Thibaut argued that the Indian Table of Jyā was possibly derived from Ptolemy’s Table of Chords by dividing Ptolemy’s arcs by 2 and retaining his values for the chords.

148/N

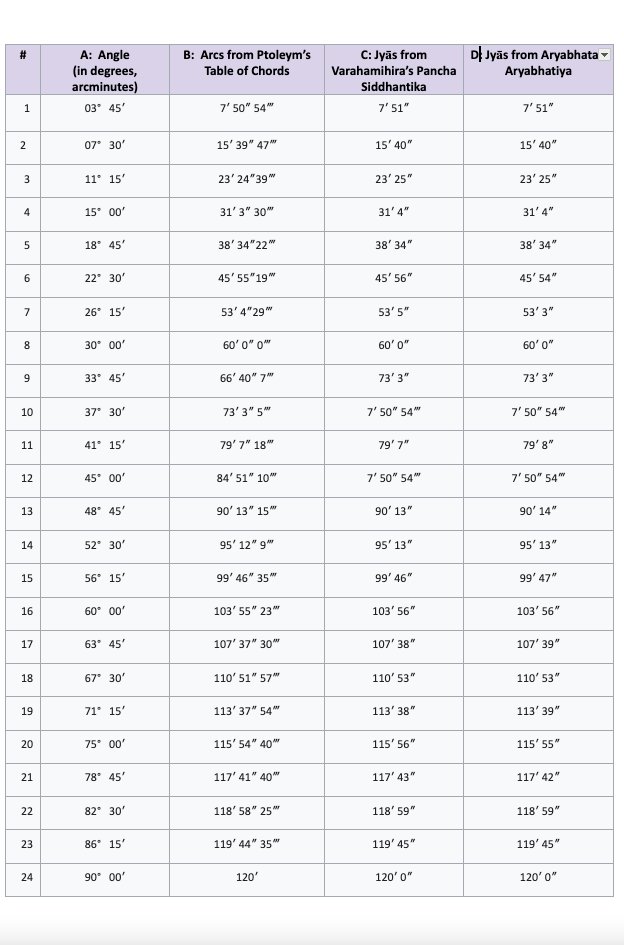

Column A gives the arcs; Column B provides the Jyās of these arcs as derived from Ptolemey’s table of chords.

Column A gives the arcs; Column B provides the Jyās of these arcs as derived from Ptolemey’s table of chords.

149/N

Column C provides the Jyās of these arcs as found in Pancha Siddhantika. Column D gives the Jyās derived from Aryabhata’s Table by substituting 120 for 3438

Column C provides the Jyās of these arcs as found in Pancha Siddhantika. Column D gives the Jyās derived from Aryabhata’s Table by substituting 120 for 3438

150/N

The basis of Thibaut’s argument is that because the values of the table of chords in Ptolemy’s works closely match with what has been provided in Panchasiddhantika, the ancient Indians must have borrowed this idea from Greek.

The basis of Thibaut’s argument is that because the values of the table of chords in Ptolemy’s works closely match with what has been provided in Panchasiddhantika, the ancient Indians must have borrowed this idea from Greek.

151/N

First, the very basis of the line of argument is simply ludicrous.

First, the very basis of the line of argument is simply ludicrous.

152/N

Imagine a person from India making a rice dish called “Chitrapaka” following a recipe which was already known for thousands of years. It consists of fragrant rice made out of onions, ginger, mushrooms, coriander, lemon, scented with saffron, musk etc.

Imagine a person from India making a rice dish called “Chitrapaka” following a recipe which was already known for thousands of years. It consists of fragrant rice made out of onions, ginger, mushrooms, coriander, lemon, scented with saffron, musk etc.

153/N

Also suppose a person from Greece makes another rice dish called “Spanakorizo” which is made with lemon, spinach and dill.

Also suppose a person from Greece makes another rice dish called “Spanakorizo” which is made with lemon, spinach and dill.

154/N

Now consider a third person who tastes both “Chitrapaka” & "Spanakorizo” and immediately claims that Indians must have learnt how to make rice dishes from Greeks because he could taste rice in both Chitrapaka & Spanakorizo.

Now consider a third person who tastes both “Chitrapaka” & "Spanakorizo” and immediately claims that Indians must have learnt how to make rice dishes from Greeks because he could taste rice in both Chitrapaka & Spanakorizo.

155/N

It would be harder to find a more idiotic argument. But some Western scholars have routinely employed such techniques to try to “prove” that ancient Indian contribution to the fields of math and science is not original

It would be harder to find a more idiotic argument. But some Western scholars have routinely employed such techniques to try to “prove” that ancient Indian contribution to the fields of math and science is not original

156/N

Secondly, Thibaut did not mention a single word about the fact that the methods used in Varahamihira’s Panchasiddhantika (Chapter 4, verses 2-5) to compute the sine values use a drastically different approach from the one used by Ptolemy.

Secondly, Thibaut did not mention a single word about the fact that the methods used in Varahamihira’s Panchasiddhantika (Chapter 4, verses 2-5) to compute the sine values use a drastically different approach from the one used by Ptolemy.

157/N

Thirdly, Thibaut conveniently ignores the value of PI used by Indian Mathematicians like Araybhata (3.1416) from which the radius in Aryabhatiyam derived and used in the Table of Jyā. Similar approach was taken by Varahamihira.

Thirdly, Thibaut conveniently ignores the value of PI used by Indian Mathematicians like Araybhata (3.1416) from which the radius in Aryabhatiyam derived and used in the Table of Jyā. Similar approach was taken by Varahamihira.

158/N

This level of accuracy in the value of PI does not occur in any of the Greek mathematical and astronomical works used for computation of table of chords

This level of accuracy in the value of PI does not occur in any of the Greek mathematical and astronomical works used for computation of table of chords

159/N

Finally, Thibaut disregarded important contexts when making comparisons between Indian & Greek approaches. An example is given below.

Finally, Thibaut disregarded important contexts when making comparisons between Indian & Greek approaches. An example is given below.

160/N

Varahamihira in Chapter 4 of Panchasiddhantika, in addition to giving values of sine, also provided methods to find latitude of a place, the ascensional differences for any given latitude-all of which are based on well-recognized ancient Indian methods

Varahamihira in Chapter 4 of Panchasiddhantika, in addition to giving values of sine, also provided methods to find latitude of a place, the ascensional differences for any given latitude-all of which are based on well-recognized ancient Indian methods

161/N

Nowhere in that chapter is there even an iota of sign of Greek influence. However Thibaut conveniently ignored all of that and proceeded to claim Greek origin of Indian sine values, simply because the final results look similar.

Nowhere in that chapter is there even an iota of sign of Greek influence. However Thibaut conveniently ignored all of that and proceeded to claim Greek origin of Indian sine values, simply because the final results look similar.

163/N

The pioneering work of ancient Indian mathematicians laid the foundation for trigonometry as we know it today. Their innovative methods for calculating the sine function reflect a deep understanding of mathematics, one that resonates through thousands of years.

The pioneering work of ancient Indian mathematicians laid the foundation for trigonometry as we know it today. Their innovative methods for calculating the sine function reflect a deep understanding of mathematics, one that resonates through thousands of years.

164/N

The Surya Siddhanta introduced the first known trigonometric functions, including the sine function, laying the groundwork for future developments in trigonometry.

The Surya Siddhanta introduced the first known trigonometric functions, including the sine function, laying the groundwork for future developments in trigonometry.

165/N

Aryabhata, in his Aryabhatiya, revolutionized mathematics with his highly precise sine table and recursive method for calculating sine values, marking a significant advancement in the field of trigonometry.

Aryabhata, in his Aryabhatiya, revolutionized mathematics with his highly precise sine table and recursive method for calculating sine values, marking a significant advancement in the field of trigonometry.

166/N

Varahamihira, in his Pancha-Siddhantika, refined trigonometric techniques and integrated them into his comprehensive astronomical treatises

Varahamihira, in his Pancha-Siddhantika, refined trigonometric techniques and integrated them into his comprehensive astronomical treatises

167/N

Bhaskara I, through his Mahabhaskariya, offered detailed explanations and approximations for sine computations, bridging the gap between theory and practical computation in trigonometry.

Bhaskara I, through his Mahabhaskariya, offered detailed explanations and approximations for sine computations, bridging the gap between theory and practical computation in trigonometry.

168/N

Brahmagupta's work in Brahmasphutasiddhanta included innovative methods for solving spherical trigonometry problems, which in turn introduced Arabs & Europeans to modern trigonometry

Brahmagupta's work in Brahmasphutasiddhanta included innovative methods for solving spherical trigonometry problems, which in turn introduced Arabs & Europeans to modern trigonometry

169/N

Madhava of Sangamagrama introduced infinite series for sine and cosine functions, paving the way for modern calculus and demonstrating remarkable mathematical foresight.

Madhava of Sangamagrama introduced infinite series for sine and cosine functions, paving the way for modern calculus and demonstrating remarkable mathematical foresight.

170/N

These contributions, marked by an unbroken chain of innovation and creativity, reflect an extraordinary continuity in the Indian mathematical tradition, where each scholar built upon the legacy of their predecessors, propelling the field of trigonometry to new heights.

These contributions, marked by an unbroken chain of innovation and creativity, reflect an extraordinary continuity in the Indian mathematical tradition, where each scholar built upon the legacy of their predecessors, propelling the field of trigonometry to new heights.

171/N

The mathematical techniques developed in ancient India for computation of sine function continue to be relevant, forming the backbone of many modern applications in science, engineering, and technology. This enduring impact highlights the timelessness of their contributions

The mathematical techniques developed in ancient India for computation of sine function continue to be relevant, forming the backbone of many modern applications in science, engineering, and technology. This enduring impact highlights the timelessness of their contributions

Loading suggestions...