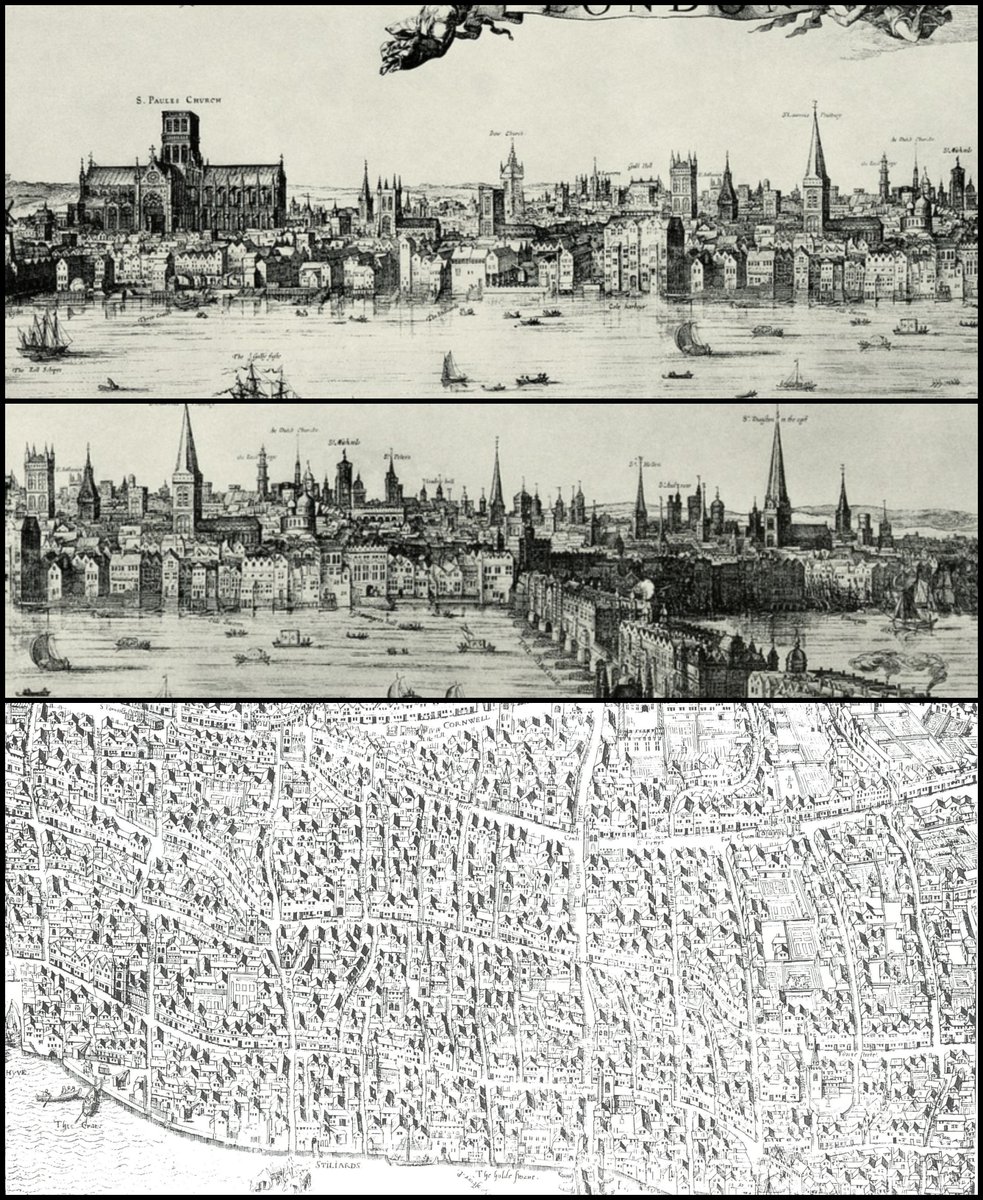

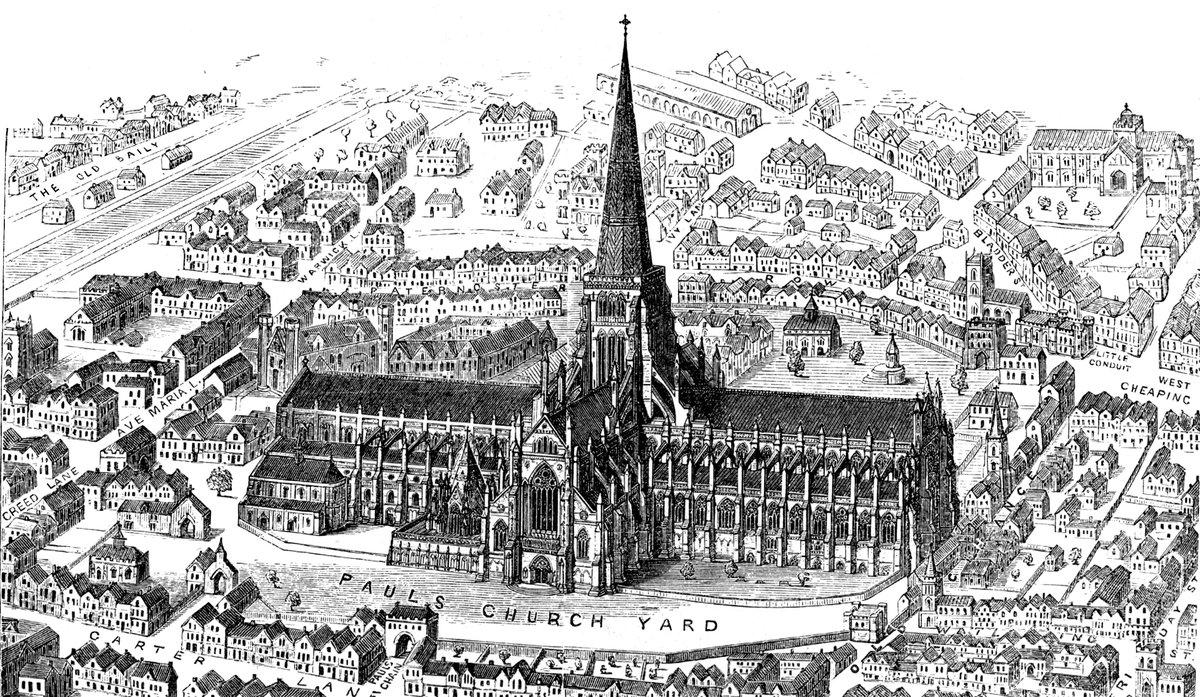

This was long before systematic studies of urban topography, public health, traffic circulation, and suchlike.

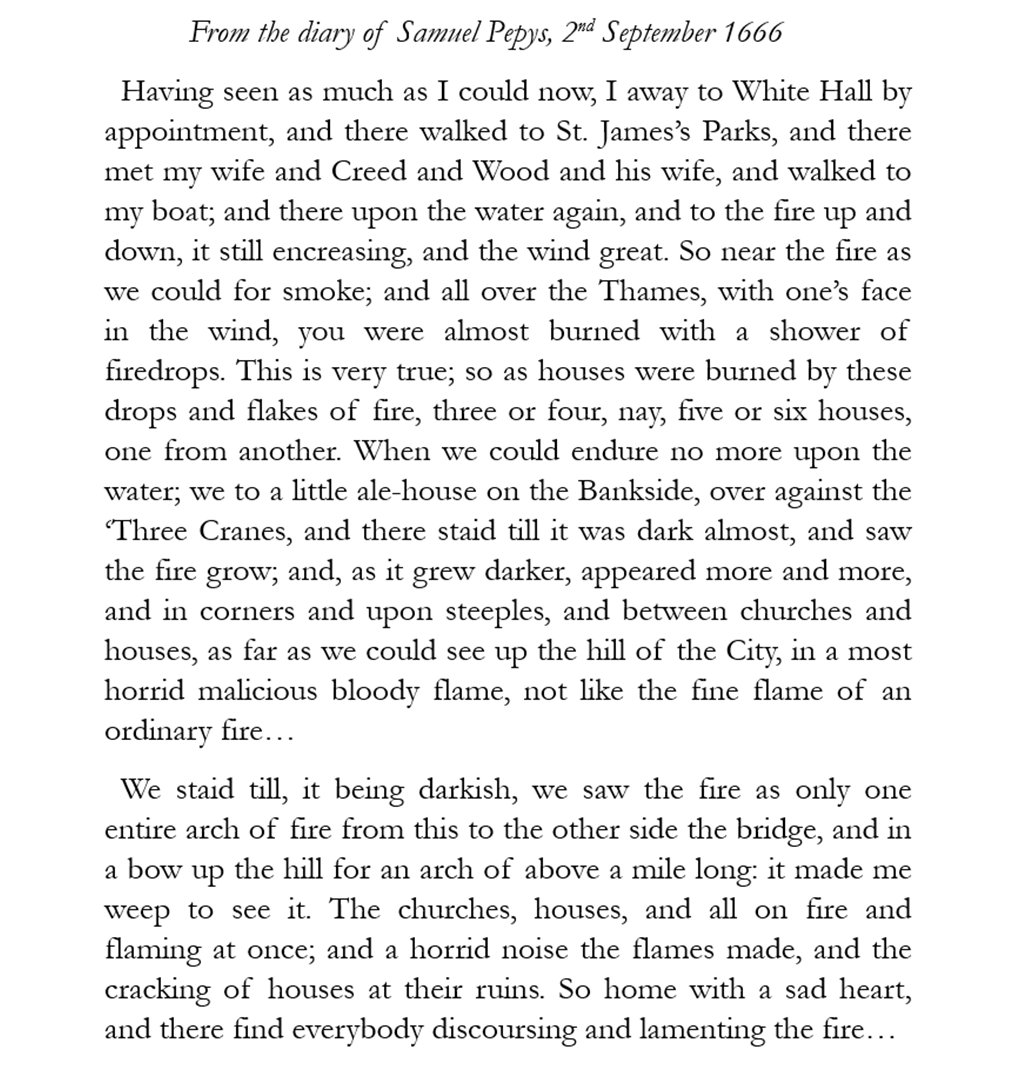

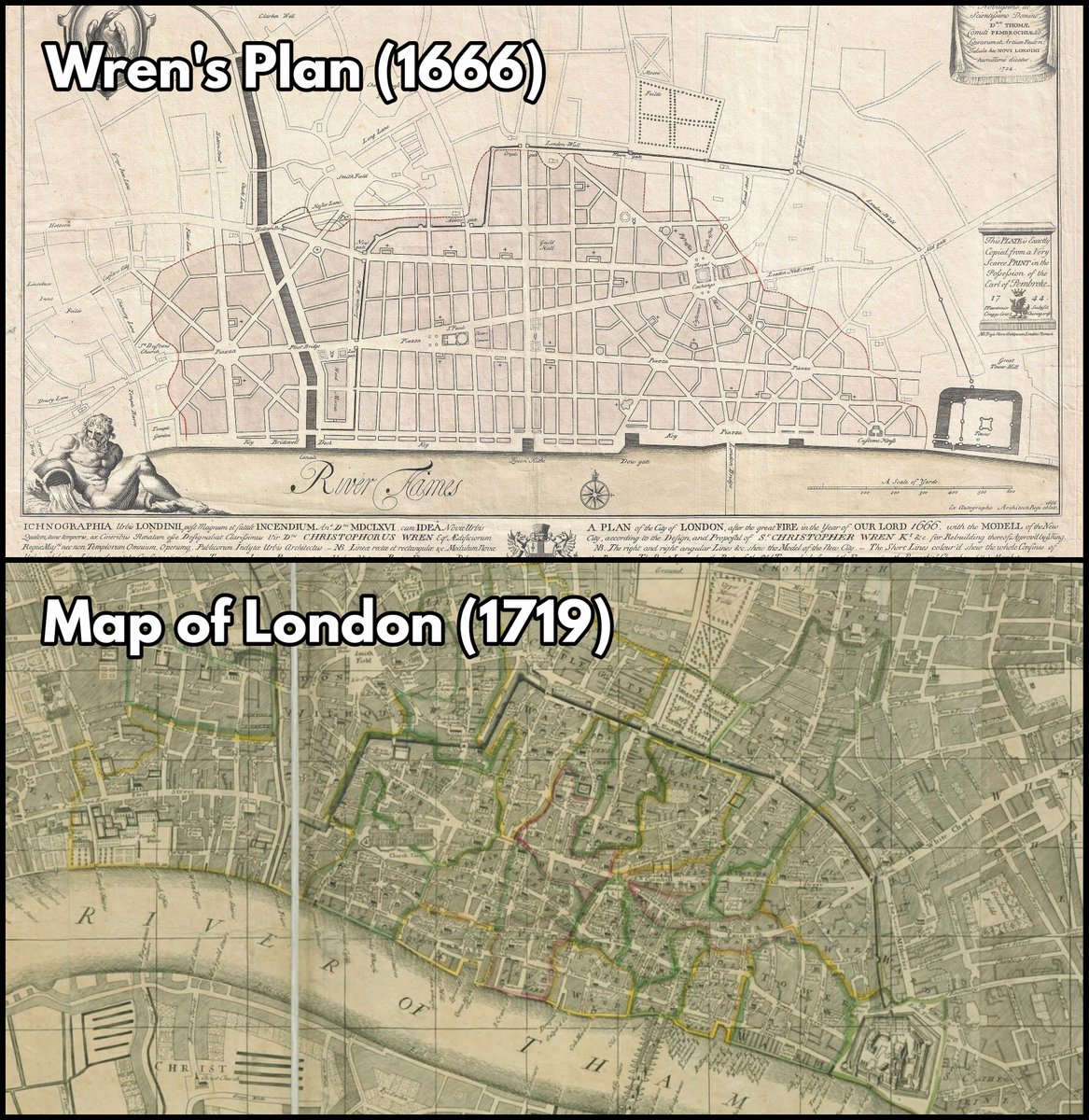

"Urban planning" as we think of it now was still a nascent science — Wren's plan was ahead of its time and would have made London a far grander city than it is today.

"Urban planning" as we think of it now was still a nascent science — Wren's plan was ahead of its time and would have made London a far grander city than it is today.

So that's why London looks the way it does — Medieval planning mixed with neoclassical design.

The Great Fire came too late for London to be rebuilt with Medieval architecture, but too soon for the large-scale urban renovations of cities like Paris or Barcelona.

The Great Fire came too late for London to be rebuilt with Medieval architecture, but too soon for the large-scale urban renovations of cities like Paris or Barcelona.

Loading suggestions...