2/N

For our journey into ancient India’s discovery of large numbers, we will look into multiple schools of thoughts including Vedic, Jaina & Buddhist.

For our journey into ancient India’s discovery of large numbers, we will look into multiple schools of thoughts including Vedic, Jaina & Buddhist.

3/N

Before we delve into the topics, it’s important to talk a bit more about the scope of the topic.

Before we delve into the topics, it’s important to talk a bit more about the scope of the topic.

4/N

Disclaimer 1: The extent of work available on the topic of large numbers from ancient Indian literature is vast. I will only address a fairly limited aspect of the foundation of large numbers in this thread.

Disclaimer 1: The extent of work available on the topic of large numbers from ancient Indian literature is vast. I will only address a fairly limited aspect of the foundation of large numbers in this thread.

5/N

Disclaimer 2: The ancient Indians delved deeply into the notion of infinity as well. While this is very related to the concept of large numbers, infinity in the Indic context is a separate topic by itself. So I will not talk about infinity in this thread.

Disclaimer 2: The ancient Indians delved deeply into the notion of infinity as well. While this is very related to the concept of large numbers, infinity in the Indic context is a separate topic by itself. So I will not talk about infinity in this thread.

6/N

Disclaimer 3: To keep the material accessible, I have avoided use of modern googological notations such as “Knuth’s up-arrow notation”, “Conway chained arrow notation” etc in representing the large numbers

Disclaimer 3: To keep the material accessible, I have avoided use of modern googological notations such as “Knuth’s up-arrow notation”, “Conway chained arrow notation” etc in representing the large numbers

7/N

With the above important disclaimers out of the way, we are now ready for the main topic.

With the above important disclaimers out of the way, we are now ready for the main topic.

9/N

Yajna (यज्ञ) or fire based ritual is a very important aspect of Vedic way of life where the primary goal is self-realization

Yajna (यज्ञ) or fire based ritual is a very important aspect of Vedic way of life where the primary goal is self-realization

10/N

Yajna (यज्ञ) in its essence represents any action or work done, inner or outer, with an attitude of surrender and offering to the superconsciousness (ब्रह्मन्) - embodiment of Truth (ऋतम्)

Yajna (यज्ञ) in its essence represents any action or work done, inner or outer, with an attitude of surrender and offering to the superconsciousness (ब्रह्मन्) - embodiment of Truth (ऋतम्)

11/N

Yajman (यजमान) in this context is the individual whose aspiration is to go through the transformative process of self-realization

Yajman (यजमान) in this context is the individual whose aspiration is to go through the transformative process of self-realization

12/N

One of the primary offerings made to fire in Yajna is Ghrita (घृत) or clarified butter. Ghrta in this context symbolizes an illumined mind, purified with the light of intuition, golden in hue.

One of the primary offerings made to fire in Yajna is Ghrita (घृत) or clarified butter. Ghrta in this context symbolizes an illumined mind, purified with the light of intuition, golden in hue.

13/N

Agni (अग्नि) is fire, the ultimate transformative agent. It symbolizes the divine Will that takes up the action in all consecration of works. Agni is a flame of force instinct with the light of divine knowledge. Agni is the seer-will in the universe unerring in all its works

Agni (अग्नि) is fire, the ultimate transformative agent. It symbolizes the divine Will that takes up the action in all consecration of works. Agni is a flame of force instinct with the light of divine knowledge. Agni is the seer-will in the universe unerring in all its works

14/N

The ground where this fire ritual is done is called Vedi (वेदी). It represents an individual with such a mind whose foundation has been prepared with pre-requisite knowledge of self realization (विद्या)

The ground where this fire ritual is done is called Vedi (वेदी). It represents an individual with such a mind whose foundation has been prepared with pre-requisite knowledge of self realization (विद्या)

15/N

The Shulba Sutras provide detailed instructions for how to perform Yajna or fire based rituals including construction of the चिति (Chiti) or altar - which requires detailed understanding of structural engineering in three dimensions.

The Shulba Sutras provide detailed instructions for how to perform Yajna or fire based rituals including construction of the चिति (Chiti) or altar - which requires detailed understanding of structural engineering in three dimensions.

16/N

Chiti (चिति) represents the core of consciousness (चित्त / Chitta) where the transformation from all layers of the being takes place with the help of Agni.

Chiti (चिति) represents the core of consciousness (चित्त / Chitta) where the transformation from all layers of the being takes place with the help of Agni.

17/N

The construction of the altar requires careful selection of different sizes of bricks called इष्टका (Ishtaka) in Sanskrit. These bricks need to carefully used to satisfy a set of geometrical constraints to form the 3D altar

The construction of the altar requires careful selection of different sizes of bricks called इष्टका (Ishtaka) in Sanskrit. These bricks need to carefully used to satisfy a set of geometrical constraints to form the 3D altar

18/N

These इष्टका or bricks represent the great resolution & will power of the individual (यजमान) who is willing to sacrifice those aspects of her being where the light of consciousness has not reached yet

These इष्टका or bricks represent the great resolution & will power of the individual (यजमान) who is willing to sacrifice those aspects of her being where the light of consciousness has not reached yet

19/N

The end-products of the Yajna are Gau (cows) & Ashva (horses) which represent two companion ideas of Light (गौ) and Energy (अश्व) - the twin aspect of all the activities of existence. They are symbolic of the richness of mental illumination & abundance of pure vital energy.

The end-products of the Yajna are Gau (cows) & Ashva (horses) which represent two companion ideas of Light (गौ) and Energy (अश्व) - the twin aspect of all the activities of existence. They are symbolic of the richness of mental illumination & abundance of pure vital energy.

20/N

Now, we are ready to see why large numbers were used in Vedic rituals.

Now, we are ready to see why large numbers were used in Vedic rituals.

22/N

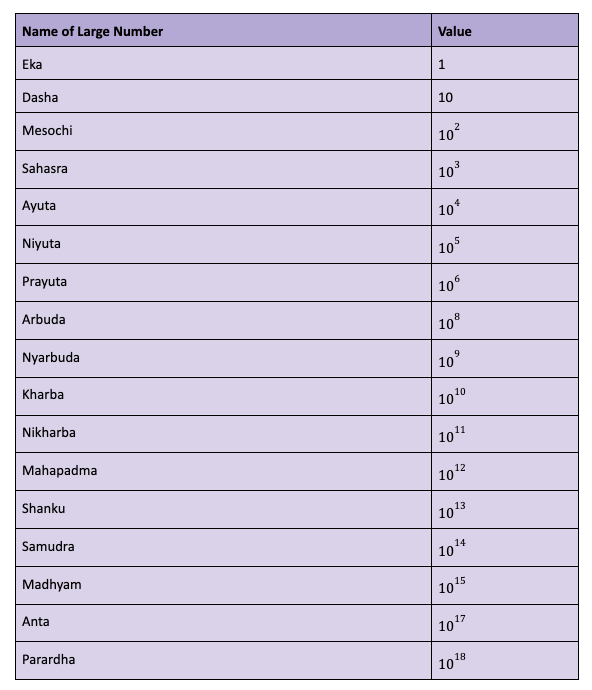

Notice, how large numbers have been used to “quantify” mental & vital abundance. Below I am providing a rough translation of Shukla Yajurveda 17.2

Notice, how large numbers have been used to “quantify” mental & vital abundance. Below I am providing a rough translation of Shukla Yajurveda 17.2

25/N

The Vedas are so ancient that they are hard to date. Traditionally they are considered “Apaurusheya'' or texts that are revealed to self-realized Rishis

The Vedas are so ancient that they are hard to date. Traditionally they are considered “Apaurusheya'' or texts that are revealed to self-realized Rishis

26/N

According to some researchers archeo-astronomy evidence exists to show that the earliest Vedic hymns were written before 22,000 BCE !

According to some researchers archeo-astronomy evidence exists to show that the earliest Vedic hymns were written before 22,000 BCE !

27/N

It is simply mind-boggling to think that numbers as large as Parardha (10^18) were known to ancient Indians possibly by 22,000 BCE

It is simply mind-boggling to think that numbers as large as Parardha (10^18) were known to ancient Indians possibly by 22,000 BCE

29/N

In Ramayana Yuddha Kanda, we find शुक (Shuka), one of the administrative chiefs of the mighty & scholarly King Ravana, was commissioned to collect information about the army of Bhagavan Ramachandra, an Avatara and the magnificent prince of Ayodhya from Ikshvaku dynasty.

In Ramayana Yuddha Kanda, we find शुक (Shuka), one of the administrative chiefs of the mighty & scholarly King Ravana, was commissioned to collect information about the army of Bhagavan Ramachandra, an Avatara and the magnificent prince of Ayodhya from Ikshvaku dynasty.

30/N

In this context, शुक gives a description of large numbers. He says “It is said by wise men that hundred thousand crores multiplied by hundred thousand crores as referred to as Shanku”

In this context, शुक gives a description of large numbers. He says “It is said by wise men that hundred thousand crores multiplied by hundred thousand crores as referred to as Shanku”

32/N

Shuka (शुक) in Ramayana then continues to define even larger numbers. He uses Shatam Sahasram & Shanku as the basis to describe increasingly larger numbers. Here we see the early application of building large numbers using a fast growing function

Shuka (शुक) in Ramayana then continues to define even larger numbers. He uses Shatam Sahasram & Shanku as the basis to describe increasingly larger numbers. Here we see the early application of building large numbers using a fast growing function

38/N

Dr. P V Vartak proposed 4 December 7324 BCE as the day of Rama-Janma. Nilesh Oak gives a date of 12200 BCE primarily based on archeo-astronomy.

Dr. P V Vartak proposed 4 December 7324 BCE as the day of Rama-Janma. Nilesh Oak gives a date of 12200 BCE primarily based on archeo-astronomy.

39/N

Essentially very large numbers such as Maha Augha (10^60) were already in common parlance by at least 7400 BCE in India.

Essentially very large numbers such as Maha Augha (10^60) were already in common parlance by at least 7400 BCE in India.

41/N

A detailed description of Vargita-samvargita is found in the Ṣaṭkhandagama, which is the foremost and oldest Digambara Jain sacred text. Ṣaṭkhandagama is dated to be compiled no later than 200 CE

A detailed description of Vargita-samvargita is found in the Ṣaṭkhandagama, which is the foremost and oldest Digambara Jain sacred text. Ṣaṭkhandagama is dated to be compiled no later than 200 CE

42/N

Acharya Virasena was a brilliant mathematician. He was also proficient in astronomy, grammar, logic, mathematics and prosody.

Acharya Virasena was a brilliant mathematician. He was also proficient in astronomy, grammar, logic, mathematics and prosody.

43/N

Virasena wrote a 72,000 shloka commentary on Shatkhandagama (known as Dhavala and the last section called Mahadhavala). Dhavala is dated to be composed no later than 9th century CE

Virasena wrote a 72,000 shloka commentary on Shatkhandagama (known as Dhavala and the last section called Mahadhavala). Dhavala is dated to be composed no later than 9th century CE

46/N

Before we delve into specific large numbers in Jaina mathematics, let’s do a quick survey of the ontology of the number system itself from a Jaina perspective.

Before we delve into specific large numbers in Jaina mathematics, let’s do a quick survey of the ontology of the number system itself from a Jaina perspective.

47/N

We are going to refer to the brilliant Jain text Anuyogadwara Sutra dated no later than 100 BCE.

We are going to refer to the brilliant Jain text Anuyogadwara Sutra dated no later than 100 BCE.

58/N

We are going to focus on the number Jaghanya Parita Asaṃkhyata which is the smallest nearly innumerable number and the largest numerable number.

We are going to focus on the number Jaghanya Parita Asaṃkhyata which is the smallest nearly innumerable number and the largest numerable number.

59/N

There is a precise definition for the number Jaghanya Parita Asaṃkhyata. To understand that we need to have a primer on Jaina cosmology.

There is a precise definition for the number Jaghanya Parita Asaṃkhyata. To understand that we need to have a primer on Jaina cosmology.

60/N

According to Jain cosmology, Jambudweepa (Jambu island) is at the center of Madhyaloka, or the middle part of the universe

According to Jain cosmology, Jambudweepa (Jambu island) is at the center of Madhyaloka, or the middle part of the universe

61/N

Jambūdvīpaprajñapti contains a description of Jambūdvīpa and life biographies of Rishabha and King Bharata.

Jambūdvīpaprajñapti contains a description of Jambūdvīpa and life biographies of Rishabha and King Bharata.

62/N

Trilokasāra, Trilokaprajñapti, Trilokadipikā and Kṣetrasamāsa are the other texts that provide the details of Jambūdvīpa and Jaina cosmology.

Trilokasāra, Trilokaprajñapti, Trilokadipikā and Kṣetrasamāsa are the other texts that provide the details of Jambūdvīpa and Jaina cosmology.

63/N

The middle world consists of a central island, which is surrounded by alternating annular oceans and islands.

The middle world consists of a central island, which is surrounded by alternating annular oceans and islands.

64/N

The central circular island called Jambudwīpa is surrounded by an annular ocean called Lavaṇa Ocean.

The central circular island called Jambudwīpa is surrounded by an annular ocean called Lavaṇa Ocean.

65/N

An annular island called Dhātakīkhaṇḍa surrounds the Lavaṇa Ocean.

An annular island called Dhātakīkhaṇḍa surrounds the Lavaṇa Ocean.

66/N

Dhātakīkhaṇḍa is surrounded by an annular ocean called Kālodadhi, which is again surrounded by an island called Puṣkaravara.

Dhātakīkhaṇḍa is surrounded by an annular ocean called Kālodadhi, which is again surrounded by an island called Puṣkaravara.

67/N

This pattern continues till the edge of the universe. The number of these concentric islands and oceans is extremely large.

This pattern continues till the edge of the universe. The number of these concentric islands and oceans is extremely large.

82/N

As will be seen below, the number jaghanya-parita-asamkhyata is very large. We will find a tight lower bound for its value.

As will be seen below, the number jaghanya-parita-asamkhyata is very large. We will find a tight lower bound for its value.

83/N

However, before we can find a lower value, we need to find a recursive relation between n_(i+1) and n_(i) using the principle of vargita-samvargita discussed earlier.

However, before we can find a lower value, we need to find a recursive relation between n_(i+1) and n_(i) using the principle of vargita-samvargita discussed earlier.

88/N

The Lalitavistara Sūtra is a Sanskrit Mahayana Buddhist sutra that tells the story of Gautama Buddha from the time of his descent from Tushita until his first sermon at Sarnath near Varanasi.

The Lalitavistara Sūtra is a Sanskrit Mahayana Buddhist sutra that tells the story of Gautama Buddha from the time of his descent from Tushita until his first sermon at Sarnath near Varanasi.

89/N

In the 12th chapter of Lalitavistara Sutra (शिल्पसंदर्शनपरिवर्तः), we find that grand preparation for selecting a bridegroom for the Prince Sarvarthasiddha (Buddha) was ongoing in Kapilavastu.

In the 12th chapter of Lalitavistara Sutra (शिल्पसंदर्शनपरिवर्तः), we find that grand preparation for selecting a bridegroom for the Prince Sarvarthasiddha (Buddha) was ongoing in Kapilavastu.

92/N

Prince Sarvarthasiddha (Buddha) did not want a regular princess to marry.

Prince Sarvarthasiddha (Buddha) did not want a regular princess to marry.

93/N

The prince wrote a collection of verses describing the desired qualities of the bride which included: knowledge of the Dharma, nobility of thoughts, elegance of appearance, prosperity of mind, expertise in public administration & public speech.

The prince wrote a collection of verses describing the desired qualities of the bride which included: knowledge of the Dharma, nobility of thoughts, elegance of appearance, prosperity of mind, expertise in public administration & public speech.

94/N

Gopa, daughter of Dandapani, from Kapilavastu was exquisitely beautiful & wise. She had all the qualities Sarvarthasiddha was looking for.

Gopa, daughter of Dandapani, from Kapilavastu was exquisitely beautiful & wise. She had all the qualities Sarvarthasiddha was looking for.

95/N

Shudhhodana, father of Sarvarthasiddha sent the marriage proposal for Gopa and his son to Dandapani, father of the future bride.

Shudhhodana, father of Sarvarthasiddha sent the marriage proposal for Gopa and his son to Dandapani, father of the future bride.

96/N

However Dandapani sent a message back saying “We have a family custom not to have our daughter married to someone who is not an expert in art such as swordsmanship, wrestling and topics of science such as mathematics & astronomy”

However Dandapani sent a message back saying “We have a family custom not to have our daughter married to someone who is not an expert in art such as swordsmanship, wrestling and topics of science such as mathematics & astronomy”

97/N

Given this condition from the bride’s family, a grand event was held, where five hundred Shakya princes were invited in a competition where prince Sarvarthasiddha could compete & demonstrate his expertise on topics of art and science.

Given this condition from the bride’s family, a grand event was held, where five hundred Shakya princes were invited in a competition where prince Sarvarthasiddha could compete & demonstrate his expertise on topics of art and science.

98/N

In that grand competition, Sarvarthasiddha had to compete with a brilliant mathematician from Kapilavastu named Arjuna.

In that grand competition, Sarvarthasiddha had to compete with a brilliant mathematician from Kapilavastu named Arjuna.

99/N

Arjuna asked Sarvarthasiddha, “Do you, Prince, know the order of reckoning after a Koti Shata (10 raised to the power of 9)” ?

Arjuna asked Sarvarthasiddha, “Do you, Prince, know the order of reckoning after a Koti Shata (10 raised to the power of 9)” ?

110/N

Sarvarthasiddha showed off his skills in mathematics by citing the names of the powers of ten, up to “Tallakshana”, which equals to 10 raised to the power of 53.

Sarvarthasiddha showed off his skills in mathematics by citing the names of the powers of ten, up to “Tallakshana”, which equals to 10 raised to the power of 53.

103/N

But Sarvarthasiddha did not stop there. He then explained how this series can be extended geometrically.

But Sarvarthasiddha did not stop there. He then explained how this series can be extended geometrically.

104/N

He starts from Dhvajagravati (10 raised to the power of 99). The last number at which he arrived at after going through seven successive steps was Paramanurajahpravesha (परमानुरजःप्रवेश), which is 10 raised to the power of 421

He starts from Dhvajagravati (10 raised to the power of 99). The last number at which he arrived at after going through seven successive steps was Paramanurajahpravesha (परमानुरजःप्रवेश), which is 10 raised to the power of 421

106/N

The very large ntity परमानुरजःप्रवेश (10 ^ 421) has been compared with the conceptual vastness of Tathagata Bodhisattva.

The very large ntity परमानुरजःप्रवेश (10 ^ 421) has been compared with the conceptual vastness of Tathagata Bodhisattva.

108/N

Buddhāvataṃsaka Sūtra is one of the most influential Mahāyāna Buddhist sutras. It is also often referred to as the Avataṃsaka Sūtra. In Sanskrit, the term Avataṃsaka means “a great number,” “a multitude,” or “a collection.”

Buddhāvataṃsaka Sūtra is one of the most influential Mahāyāna Buddhist sutras. It is also often referred to as the Avataṃsaka Sūtra. In Sanskrit, the term Avataṃsaka means “a great number,” “a multitude,” or “a collection.”

109/N

The original Buddhāvataṃsaka Sūtra was in Sanskrit, which was later translated to Tibetan & Chinese

The original Buddhāvataṃsaka Sūtra was in Sanskrit, which was later translated to Tibetan & Chinese

110/N

According to Akira Hirakawa and Otake Susumu Sanskrit original of Buddhāvataṃsaka Sūtra, was compiled in India about 500 years after death of Gautama Buddha

According to Akira Hirakawa and Otake Susumu Sanskrit original of Buddhāvataṃsaka Sūtra, was compiled in India about 500 years after death of Gautama Buddha

111/N

In this text we will find how Buddha provides a fast growing function. The last number in the series is a called “Anabhilapyanabhilapya -Parivarta” which is 10 raised to the power of 37,218,383,881,977,700,000,000,000,000,000,000,000

In this text we will find how Buddha provides a fast growing function. The last number in the series is a called “Anabhilapyanabhilapya -Parivarta” which is 10 raised to the power of 37,218,383,881,977,700,000,000,000,000,000,000,000

112/N

In the 30th Book of the Buddhāvataṃsaka Sūtra (असंख्येय), we find a Bodhisattva asking the Buddha: “O Bhagavat, when expounding on the Dharma, the buddhas, the tathāgatas, use very large numbers”

In the 30th Book of the Buddhāvataṃsaka Sūtra (असंख्येय), we find a Bodhisattva asking the Buddha: “O Bhagavat, when expounding on the Dharma, the buddhas, the tathāgatas, use very large numbers”

113/N

Bodhisattva continues: “The tathāgatas use such numbers as ‘asaṃkhyeya,’ ‘measureless,’ ‘bound- less,’ ‘incomparable,’ ‘innumerable,’ ‘indescribable,’ ‘inconceivable,’ ‘incalculable,’ ‘ineffable.’ O Bhagavat, what is meant by ‘asaṃkhyeya’ and so forth?

Bodhisattva continues: “The tathāgatas use such numbers as ‘asaṃkhyeya,’ ‘measureless,’ ‘bound- less,’ ‘incomparable,’ ‘innumerable,’ ‘indescribable,’ ‘inconceivable,’ ‘incalculable,’ ‘ineffable.’ O Bhagavat, what is meant by ‘asaṃkhyeya’ and so forth?

114/N

The Buddha then goes into this amazing discourse of listing numbers in chronological order.

The Buddha then goes into this amazing discourse of listing numbers in chronological order.

115/N

Buddha starts from Koti (10 raised to the power 7) and ends up this mind-bogglingly large umber “Anabhilapyanabhilapya-Parivarta” which is same as 10 raised to the power of 1,163,074,496,311,800,000,000,000,000,000,000,000

Buddha starts from Koti (10 raised to the power 7) and ends up this mind-bogglingly large umber “Anabhilapyanabhilapya-Parivarta” which is same as 10 raised to the power of 1,163,074,496,311,800,000,000,000,000,000,000,000

116/N

Because the list of these large numbers in Buddhāvataṃsaka Sūtra is long, I will break it up into multiple tables.

Because the list of these large numbers in Buddhāvataṃsaka Sūtra is long, I will break it up into multiple tables.

124/N

The final table from Buddhāvataṃsaka Sūtra starts from Aparyanta-Parivarta (10 raised to the power of 277,298,568,799,925,000,000,000,000,000) and ends with Anabhilapyanabhilapya

-Parivarta

The final table from Buddhāvataṃsaka Sūtra starts from Aparyanta-Parivarta (10 raised to the power of 277,298,568,799,925,000,000,000,000,000) and ends with Anabhilapyanabhilapya

-Parivarta

126/N

In the European context, Archimedes, a Greek polymath, sometime in the 300 BCE started experimenting with large number in his book “Sand Reckoner”

In the European context, Archimedes, a Greek polymath, sometime in the 300 BCE started experimenting with large number in his book “Sand Reckoner”

127/N

Ancient Indians not only pioneered the study of large numbers at least 10000 years before Greeks (or any Europeans), but were using it in both mathematical work as well as in literature and poetry.

Ancient Indians not only pioneered the study of large numbers at least 10000 years before Greeks (or any Europeans), but were using it in both mathematical work as well as in literature and poetry.

128/N

The study of large numbers invented in India is today known as googology. It is an important tool for understanding some of the fundamental principles of mathematics and for exploring the limits of what is currently known about the properties of large numbers

The study of large numbers invented in India is today known as googology. It is an important tool for understanding some of the fundamental principles of mathematics and for exploring the limits of what is currently known about the properties of large numbers

Loading suggestions...