2/

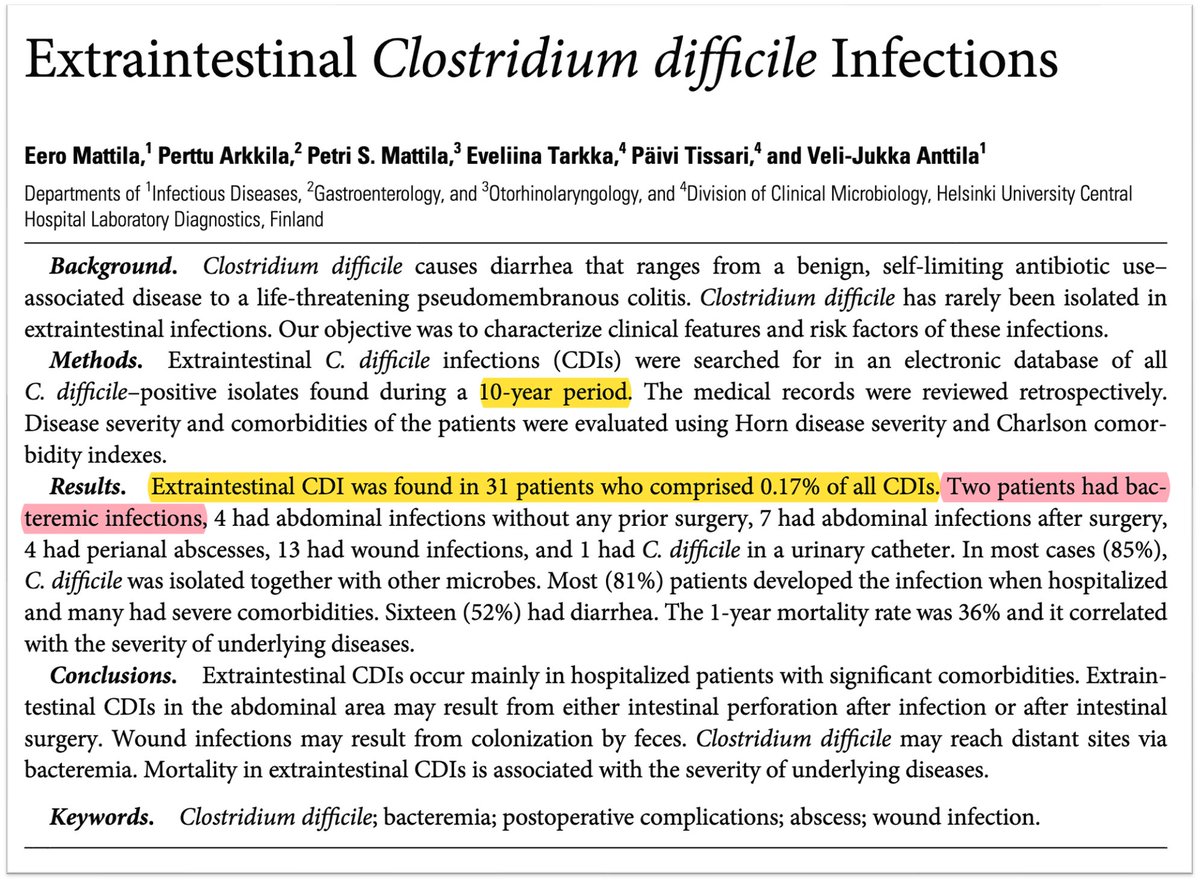

Extraintestinal manifestations of CDI are rare, in general.

One study examined a 10-year study and found that just 31 of 18,570 (0.17%) cases of CDI were extraintestinal.

💡And only 2 (0.01%) were bloodstream infections!

pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov

Extraintestinal manifestations of CDI are rare, in general.

One study examined a 10-year study and found that just 31 of 18,570 (0.17%) cases of CDI were extraintestinal.

💡And only 2 (0.01%) were bloodstream infections!

pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov

3/

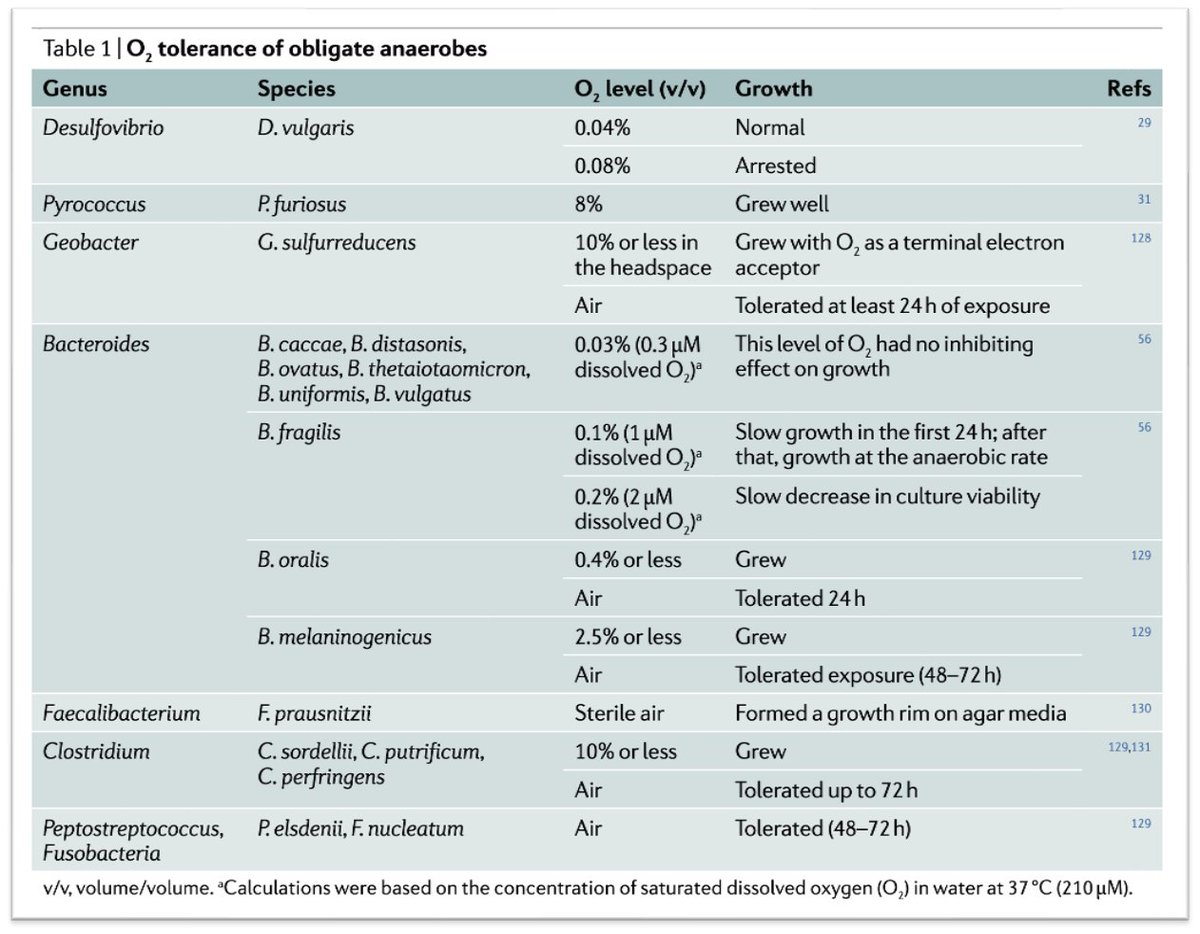

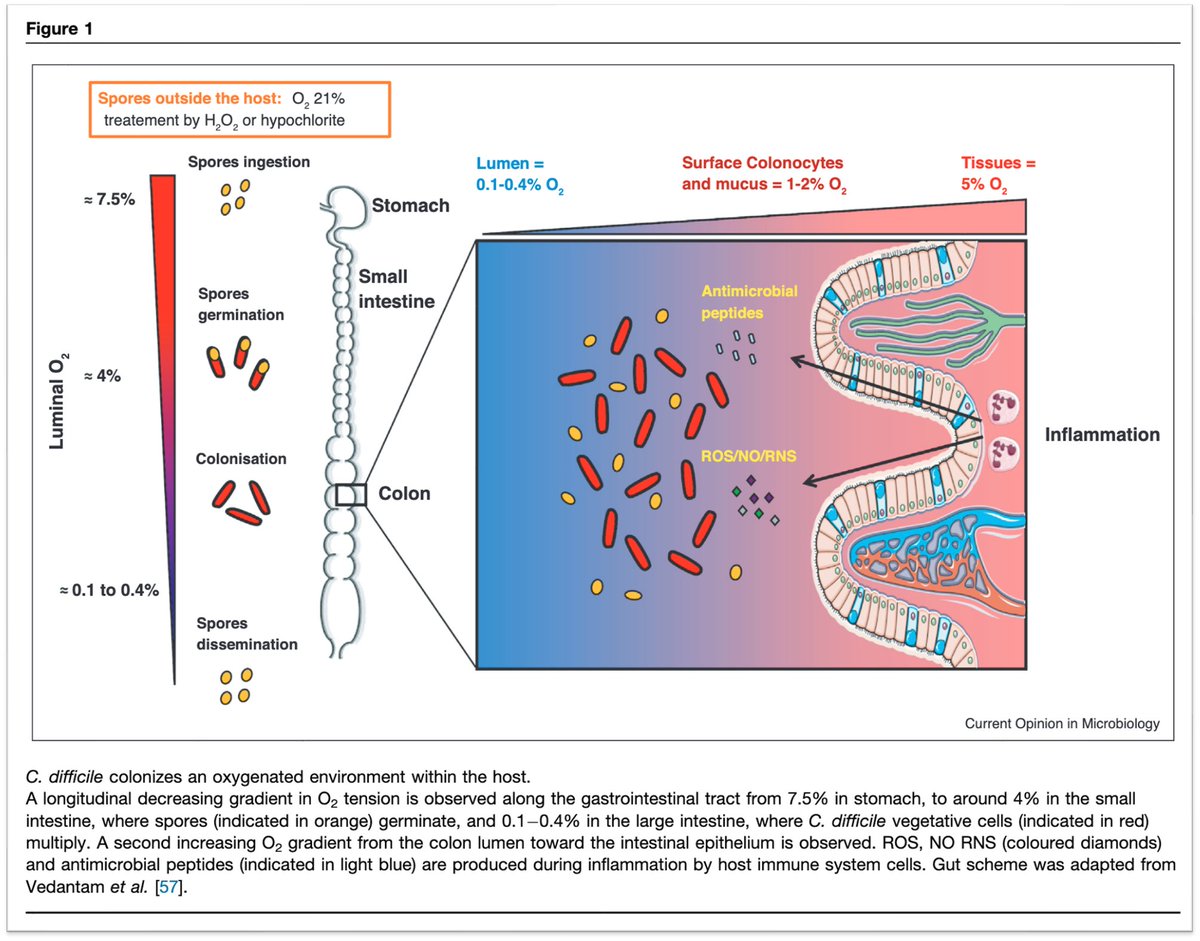

As a reminder, C. difficile is an obligate anaerobe. As with other obligate anaerobes, it prefers environments with low to no oxygen.

This explains why anaerobic bacteria like C. difficile colonize the colon.

pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov

As a reminder, C. difficile is an obligate anaerobe. As with other obligate anaerobes, it prefers environments with low to no oxygen.

This explains why anaerobic bacteria like C. difficile colonize the colon.

pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov

4/

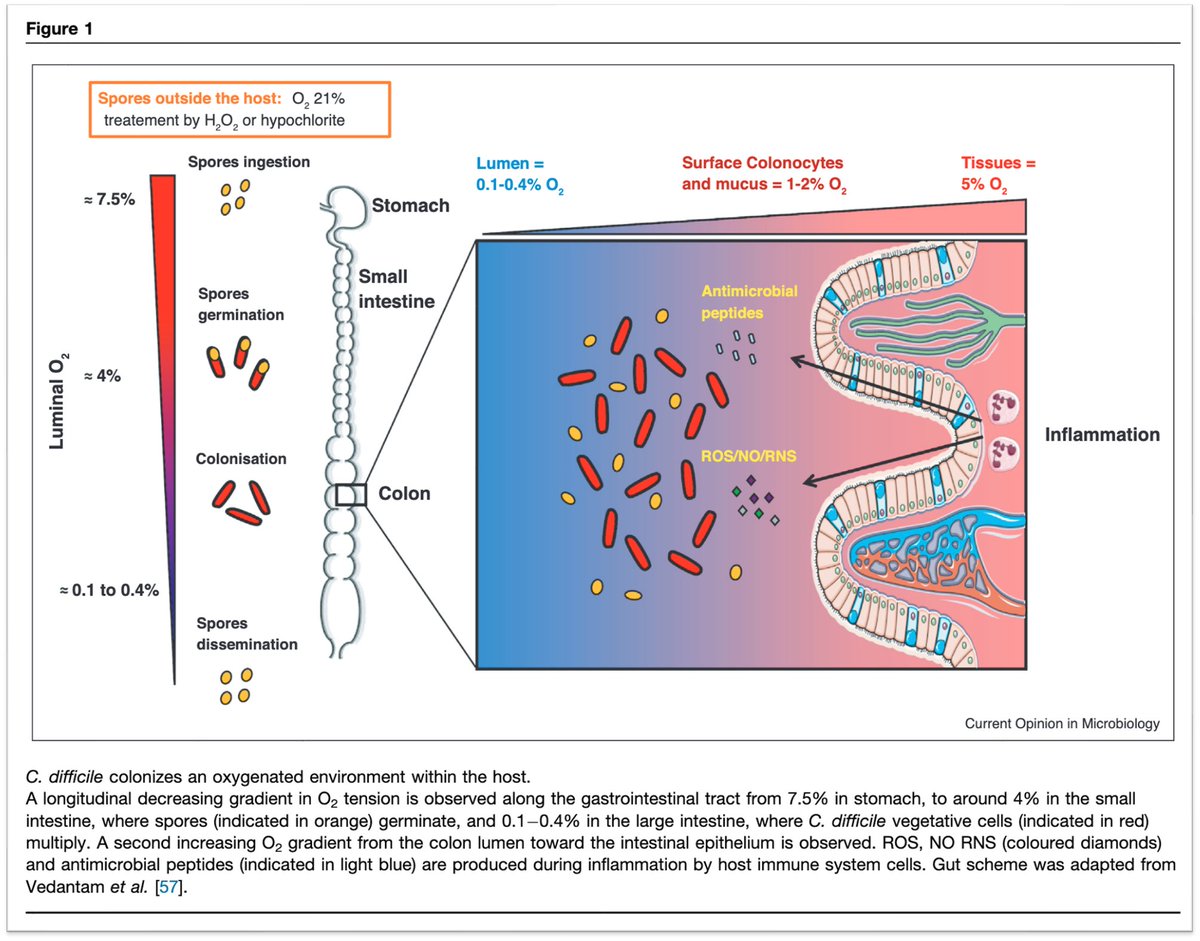

Understanding the geographic predilection of C. difficile requires review of the two oxygen gradients within the gastrointestinal tract.

The first is a luminal gradient from stomach to colon.

➤Stomach 7.5% O₂

➤Small intestine 4%

➤Colon 0.1-0.4%

pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov

Understanding the geographic predilection of C. difficile requires review of the two oxygen gradients within the gastrointestinal tract.

The first is a luminal gradient from stomach to colon.

➤Stomach 7.5% O₂

➤Small intestine 4%

➤Colon 0.1-0.4%

pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov

5/

The second oxygen gradient is from intestinal epithelium to lumen.

➤Intestinal epithelium 5% O₂

➤Surface colonocytes and mucus 1-2%

➤Colonic lumen 0.1-0.4%

💡Notice that both gradients end with a colonic lumen that lacks oxygen.

pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov

The second oxygen gradient is from intestinal epithelium to lumen.

➤Intestinal epithelium 5% O₂

➤Surface colonocytes and mucus 1-2%

➤Colonic lumen 0.1-0.4%

💡Notice that both gradients end with a colonic lumen that lacks oxygen.

pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov

6/

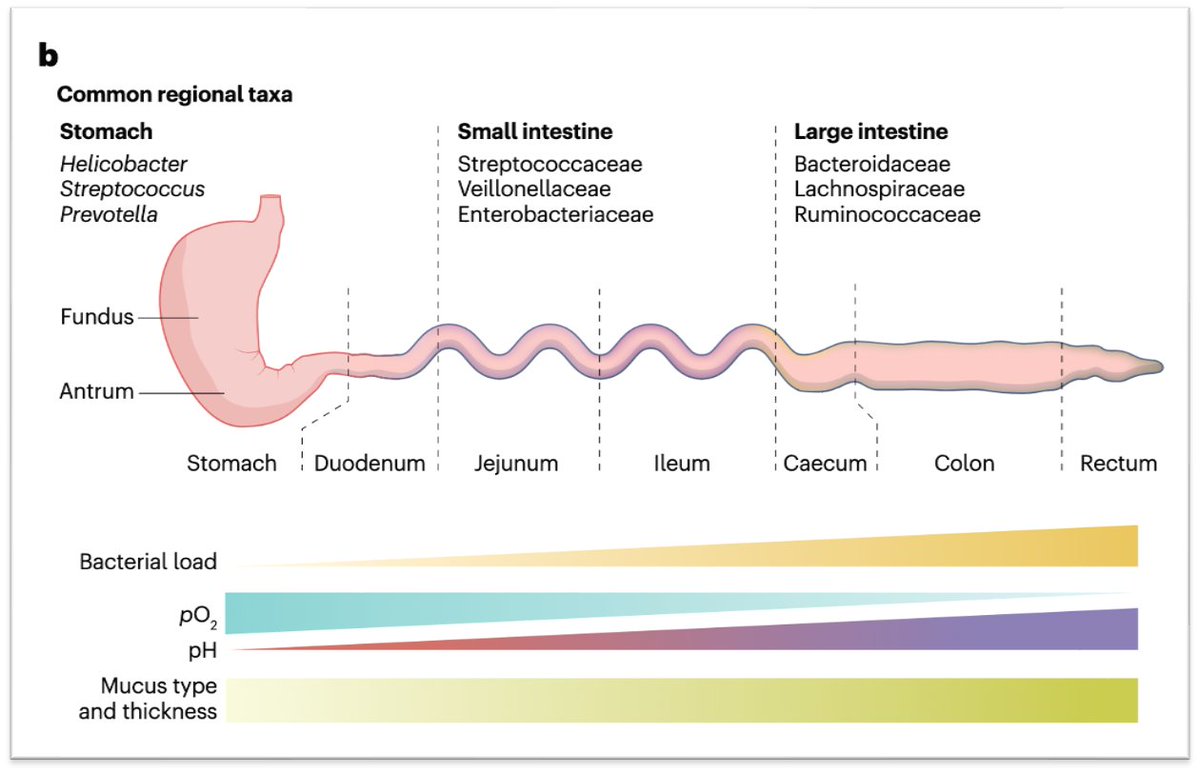

Obligate anaerobes follow a similar gradient and are found in the greatest number in the colonic lumen.

💡While the small intestine is dominated by facultative anaerobes (e.g., E. coli), 99% of bacterial species in the colon are obligate anaerobes.

pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov

Obligate anaerobes follow a similar gradient and are found in the greatest number in the colonic lumen.

💡While the small intestine is dominated by facultative anaerobes (e.g., E. coli), 99% of bacterial species in the colon are obligate anaerobes.

pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov

7/

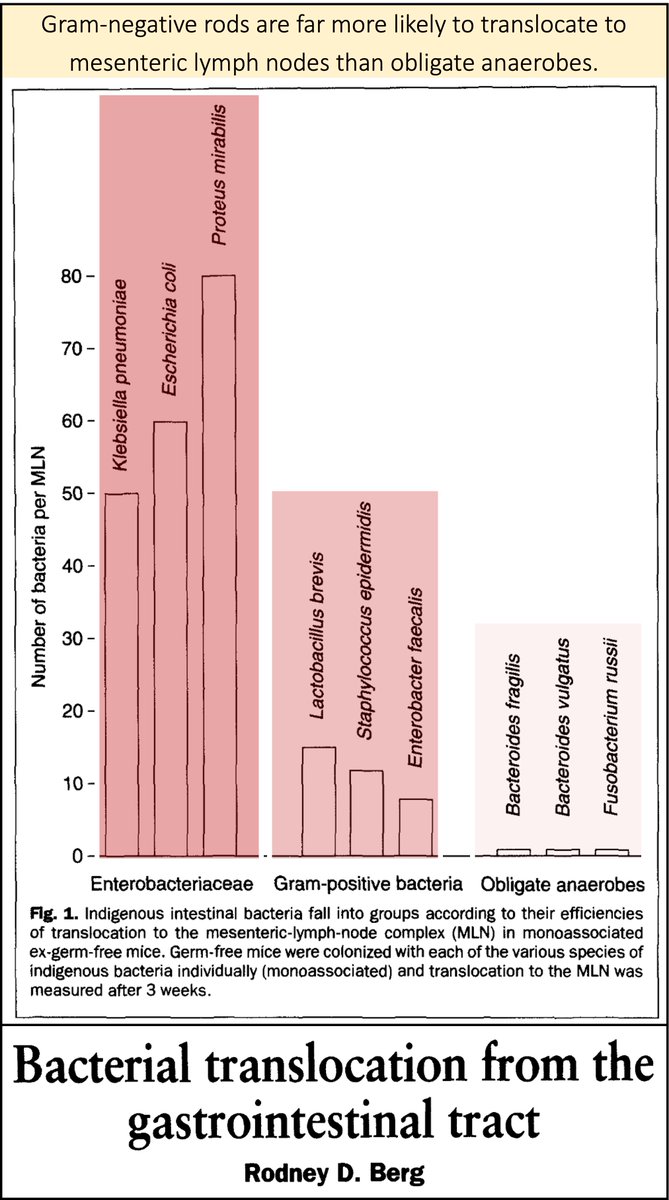

I suspect the above geography results in two barriers to easy entry of C. difficile into the blood.

(1) It has a "longer" road to travel from lumen to blood than bacteria settled near the epithelium

(2) Along the way, it faces an increasingly inhospitable oxygen tension

I suspect the above geography results in two barriers to easy entry of C. difficile into the blood.

(1) It has a "longer" road to travel from lumen to blood than bacteria settled near the epithelium

(2) Along the way, it faces an increasingly inhospitable oxygen tension

8/

Support for this hypothesis comes from the observation that anaerobic bacteria, like C. difficile, are far less likely to translocate the bowel wall than are facultative anaerobes, like E. coli.

pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov

Support for this hypothesis comes from the observation that anaerobic bacteria, like C. difficile, are far less likely to translocate the bowel wall than are facultative anaerobes, like E. coli.

pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov

9/

This helps explain why we don't empirically cover anaerobes when treating spontaneous bacterial peritonitis.

For more on that topic, see this thread.

x.com

This helps explain why we don't empirically cover anaerobes when treating spontaneous bacterial peritonitis.

For more on that topic, see this thread.

x.com

10/

In some ways, my original question might be more appropriately titled, "Why do we EVER see Clostridioides difficile bacteremia?"

If it is so hard to get into the blood AND the blood is oxygenated, shouldn't it be nearly impossible for C. difficile to infect the bloodstream?

In some ways, my original question might be more appropriately titled, "Why do we EVER see Clostridioides difficile bacteremia?"

If it is so hard to get into the blood AND the blood is oxygenated, shouldn't it be nearly impossible for C. difficile to infect the bloodstream?

11/

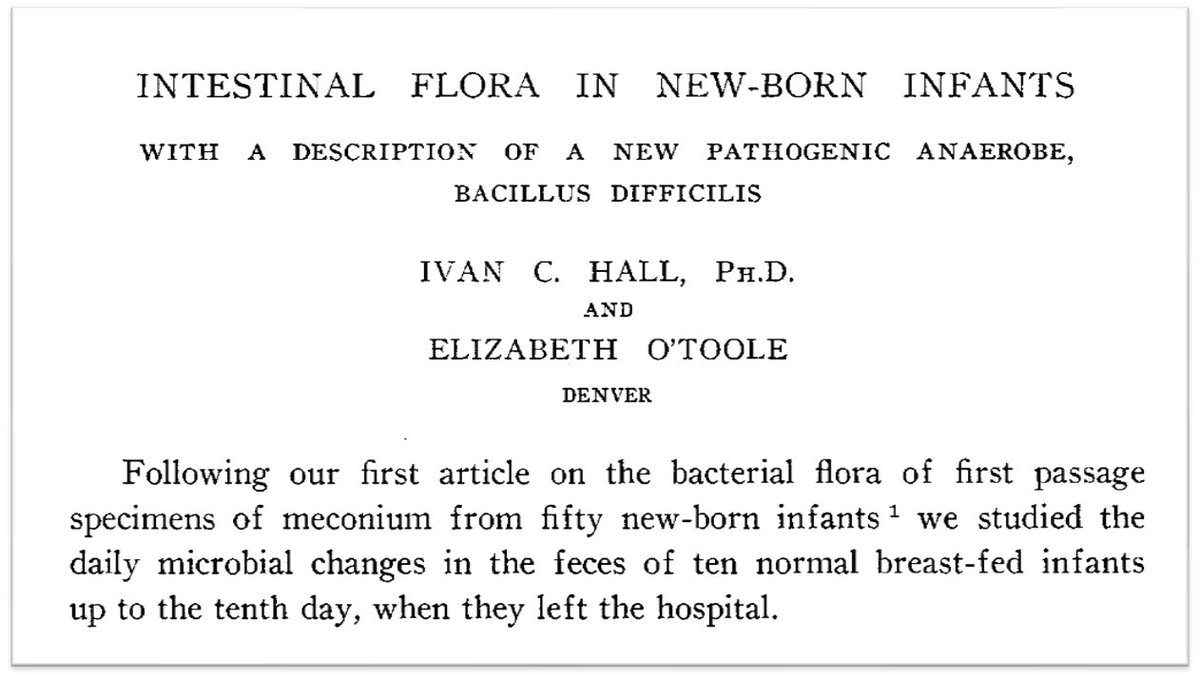

In fact, C. difficile was named specifically as it was hard to isolate.

In their 1935 description, Hall and O'Toole write, "it is therefore named Bacillus difficilis because of the unusual difficulty which was encountered in its isolation and study."

jamanetwork.com

In fact, C. difficile was named specifically as it was hard to isolate.

In their 1935 description, Hall and O'Toole write, "it is therefore named Bacillus difficilis because of the unusual difficulty which was encountered in its isolation and study."

jamanetwork.com

12/

But other anaerobes DO infect the blood.

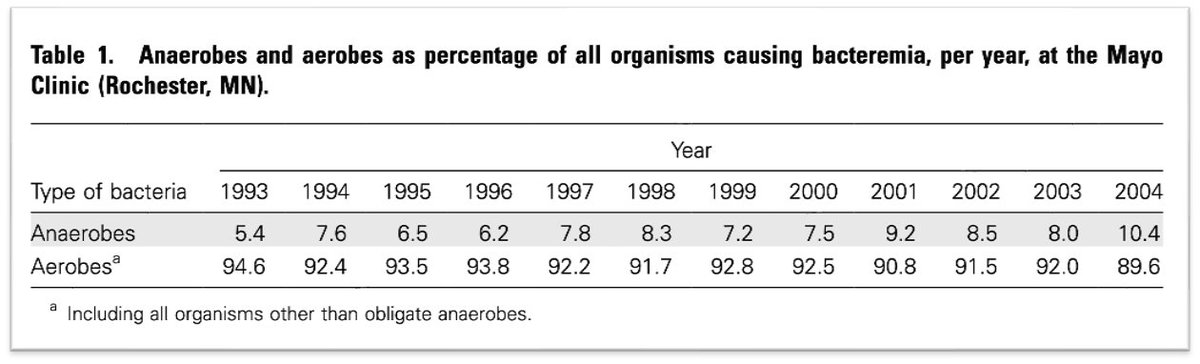

💡Cohort studies suggest anaerobic bacteria cause 5-10% of bloodstream infections.

pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov

But other anaerobes DO infect the blood.

💡Cohort studies suggest anaerobic bacteria cause 5-10% of bloodstream infections.

pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov

13/

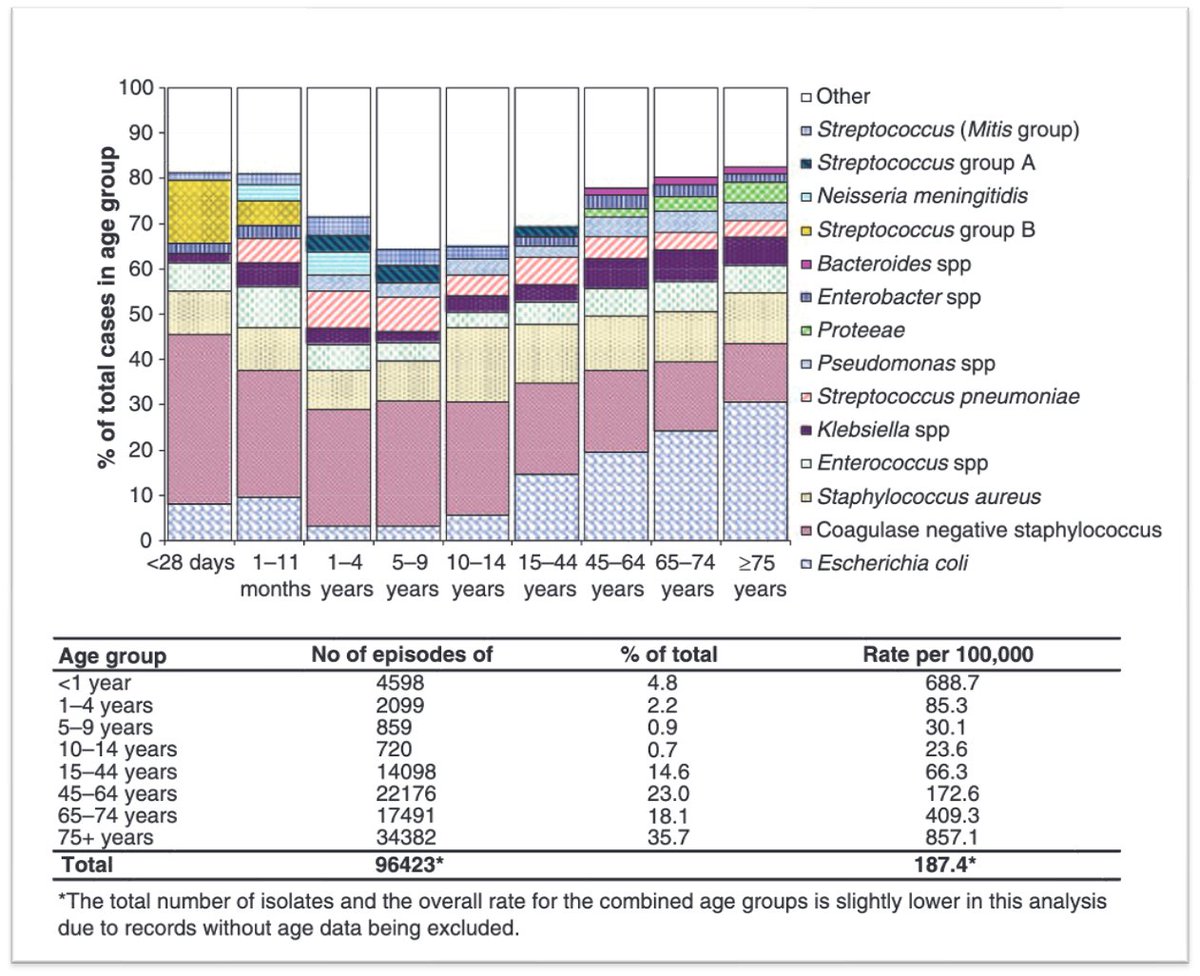

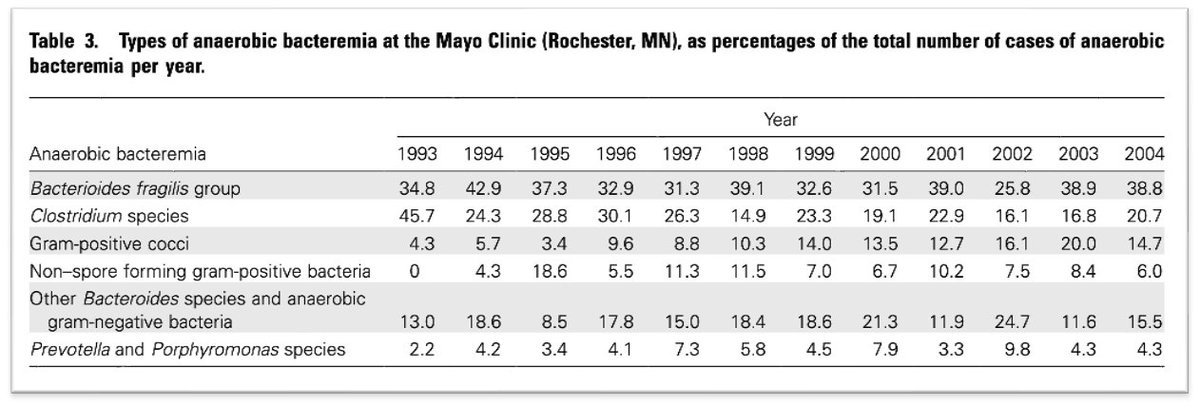

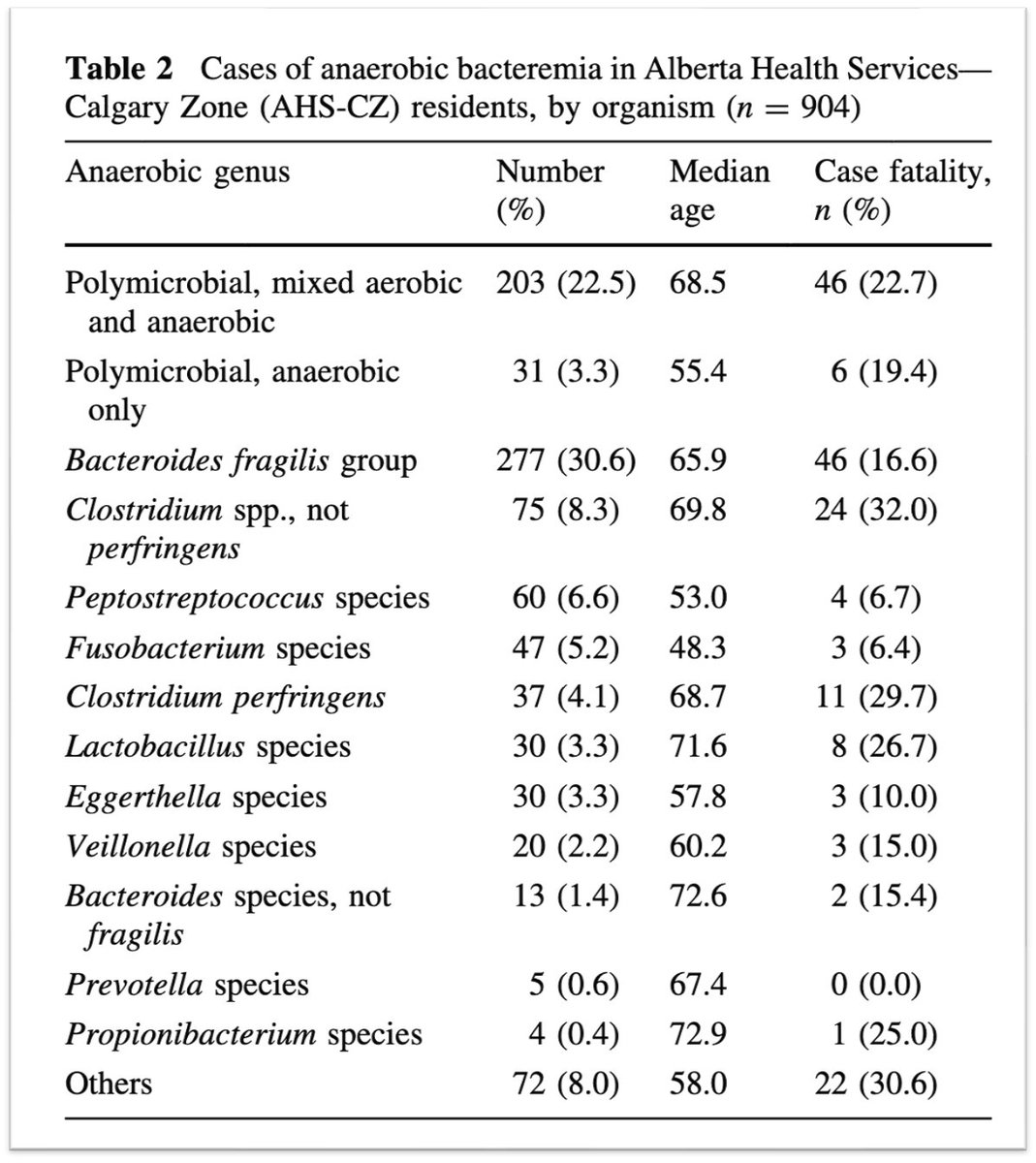

E. coli is the most common cause of bacteremia overall.

Among obligate anaerobes, Bacteroides species top the list.

pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov

pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov

E. coli is the most common cause of bacteremia overall.

Among obligate anaerobes, Bacteroides species top the list.

pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov

pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov

pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20491834/

Trends among pathogens reported as causing bacteraemia in England, 2004-2008 - PubMed

The Health Protection Agency in England operates a voluntary surveillance system that collects data...

pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17342637/

Reemergence of anaerobic bacteremia - PubMed

Anaerobic bacteremia has reemerged as a significant clinical problem. Although there are probably mu...

14/

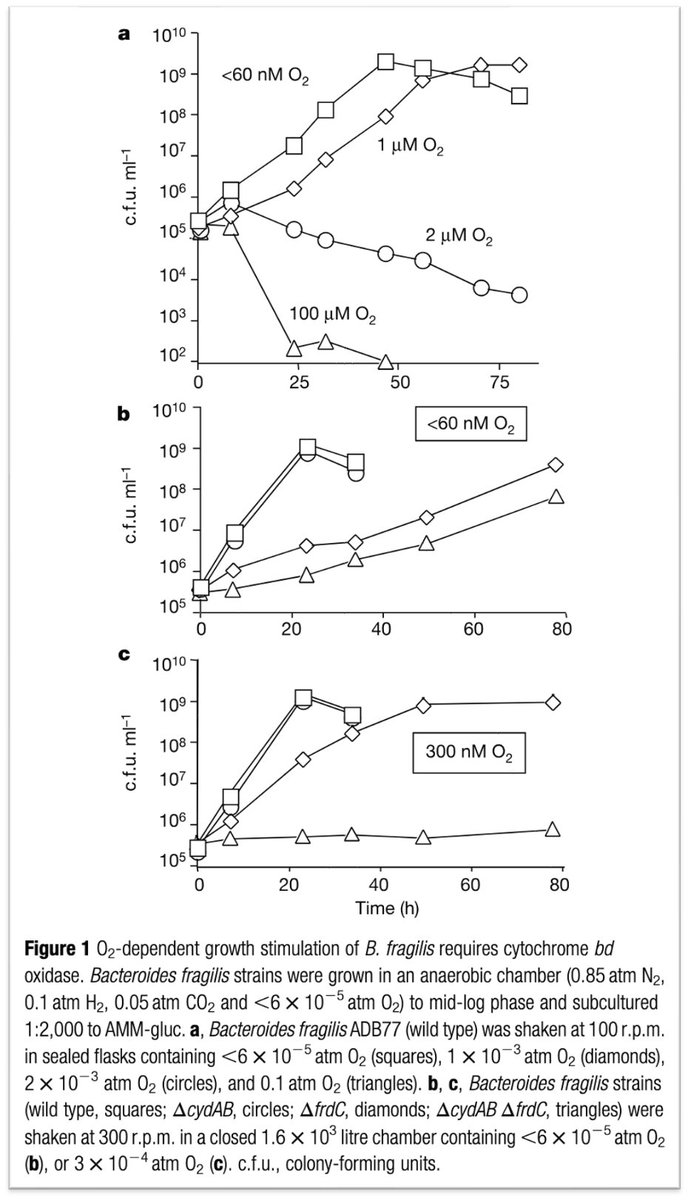

Bacteroides fragilis is interesting. Although it is an obligate anaerobe, it can use oxygen as a terminal electron acceptor at nanomolar concentrations.

This may help explain why it is the most common obligate anaerobe to be isolated in the blood.

pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov

Bacteroides fragilis is interesting. Although it is an obligate anaerobe, it can use oxygen as a terminal electron acceptor at nanomolar concentrations.

This may help explain why it is the most common obligate anaerobe to be isolated in the blood.

pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov

15/

Even C. difficile can grow at low oxygen tensions.

Studies have shown that the bacterium can grow in 1-3% oxygen and tolerate brief air exposure.

ncbi.nlm.nih.gov

Even C. difficile can grow at low oxygen tensions.

Studies have shown that the bacterium can grow in 1-3% oxygen and tolerate brief air exposure.

ncbi.nlm.nih.gov

16/

Despite its ability to grow in the presence of oxygen, C. difficile is far less commonly isolated from the blood than other Clostridial species, like Clostridium perfringens.

pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov

Despite its ability to grow in the presence of oxygen, C. difficile is far less commonly isolated from the blood than other Clostridial species, like Clostridium perfringens.

pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov

17/

Why C. difficile is less able to proliferate in the blood compared with C. perfringens is not entirely unclear.

I wasn't able to find any definitive explanations.

What have I missed?

Why C. difficile is less able to proliferate in the blood compared with C. perfringens is not entirely unclear.

I wasn't able to find any definitive explanations.

What have I missed?

18/18

𖠘 Clostridioides difficile is a rare cause of bloodstream infections

𖠘 This is likely explained, in part, by the fact that it is an obligate anaerobe

𖠘 Other obligate anaerobes can proliferate more easily; why C. difficile has such a "hard time" in the blood is unclear

𖠘 Clostridioides difficile is a rare cause of bloodstream infections

𖠘 This is likely explained, in part, by the fact that it is an obligate anaerobe

𖠘 Other obligate anaerobes can proliferate more easily; why C. difficile has such a "hard time" in the blood is unclear

جاري تحميل الاقتراحات...