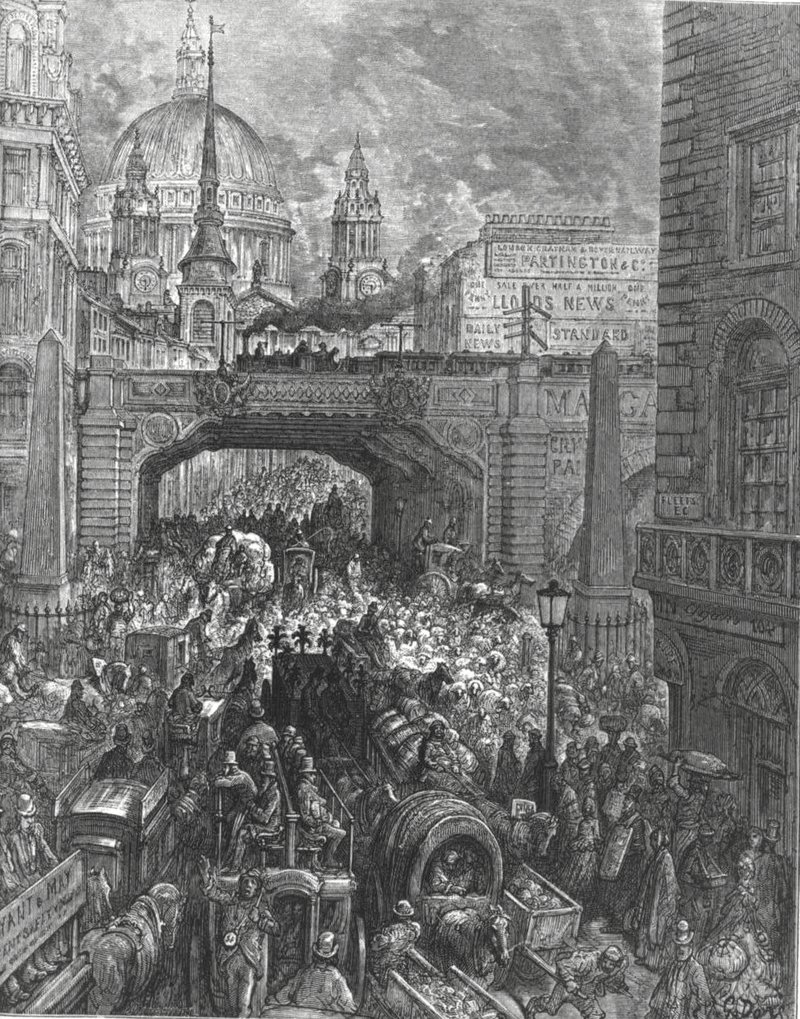

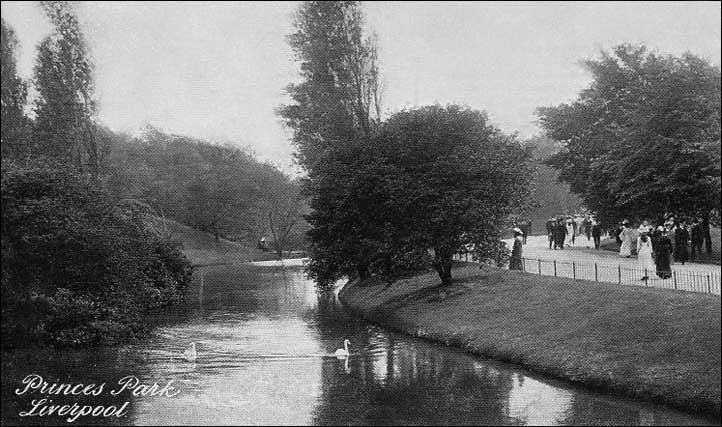

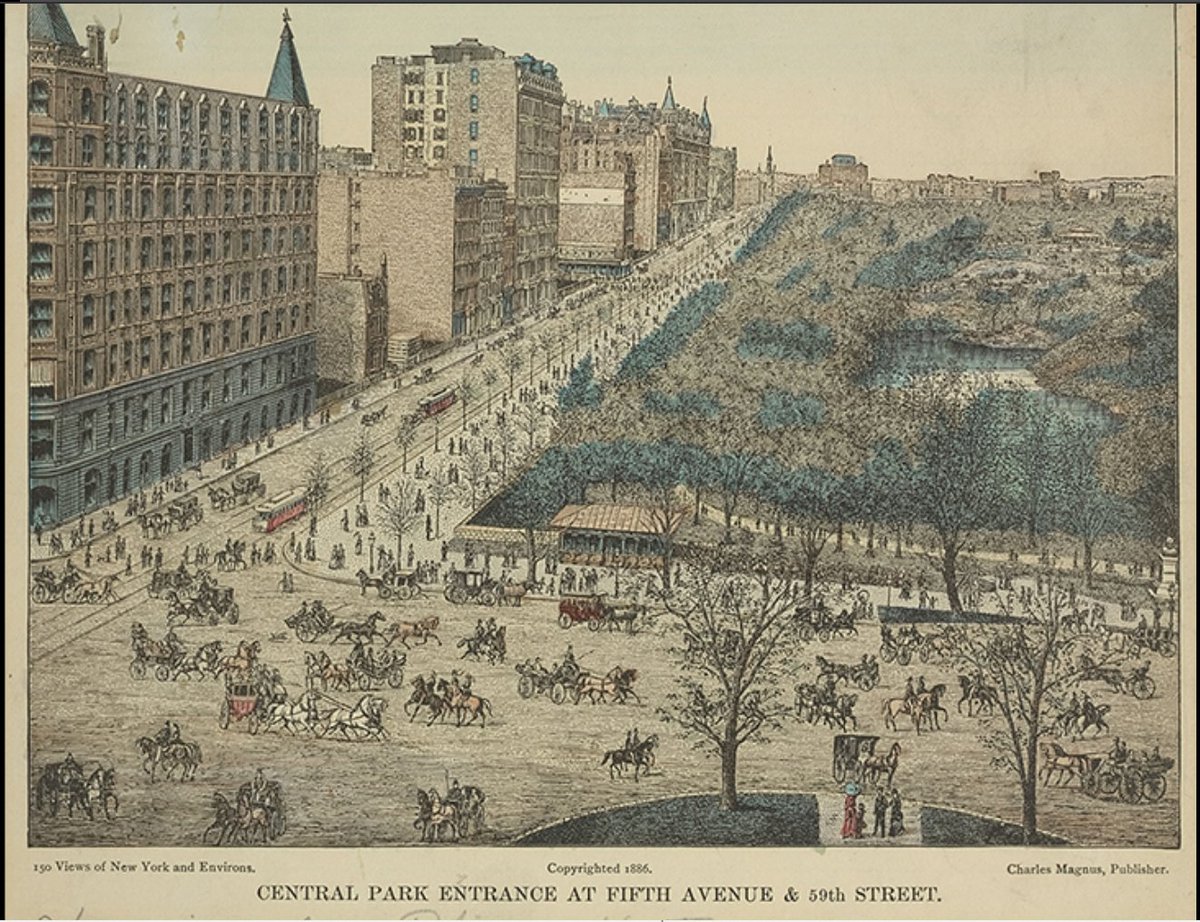

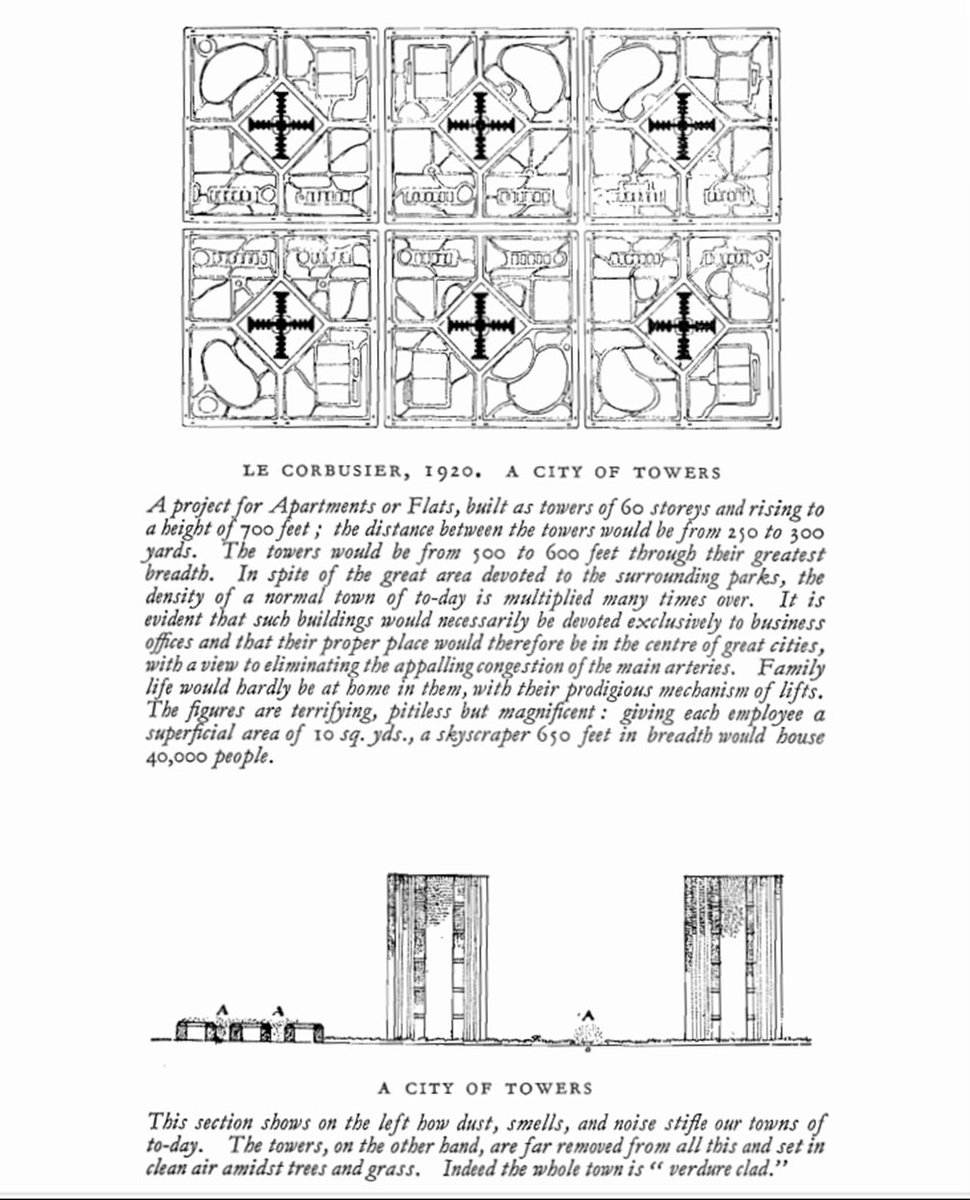

Studies have proven what we instinctively know: that people are happier in natural surroundings, that trees, flowers, rivers, & meadows are more soothing than tarmac and glass.

And this is an age when people, spending all their time online, are more stressed than ever.

And this is an age when people, spending all their time online, are more stressed than ever.

جاري تحميل الاقتراحات...