I'm excited to announce this new paper with Dylan Sullivan and Michail Moatsos. We explore the effect of capitalist reforms on extreme poverty in China. It's a surprising and fascinating story, with important implications for policy. 🧵 tandfonline.com

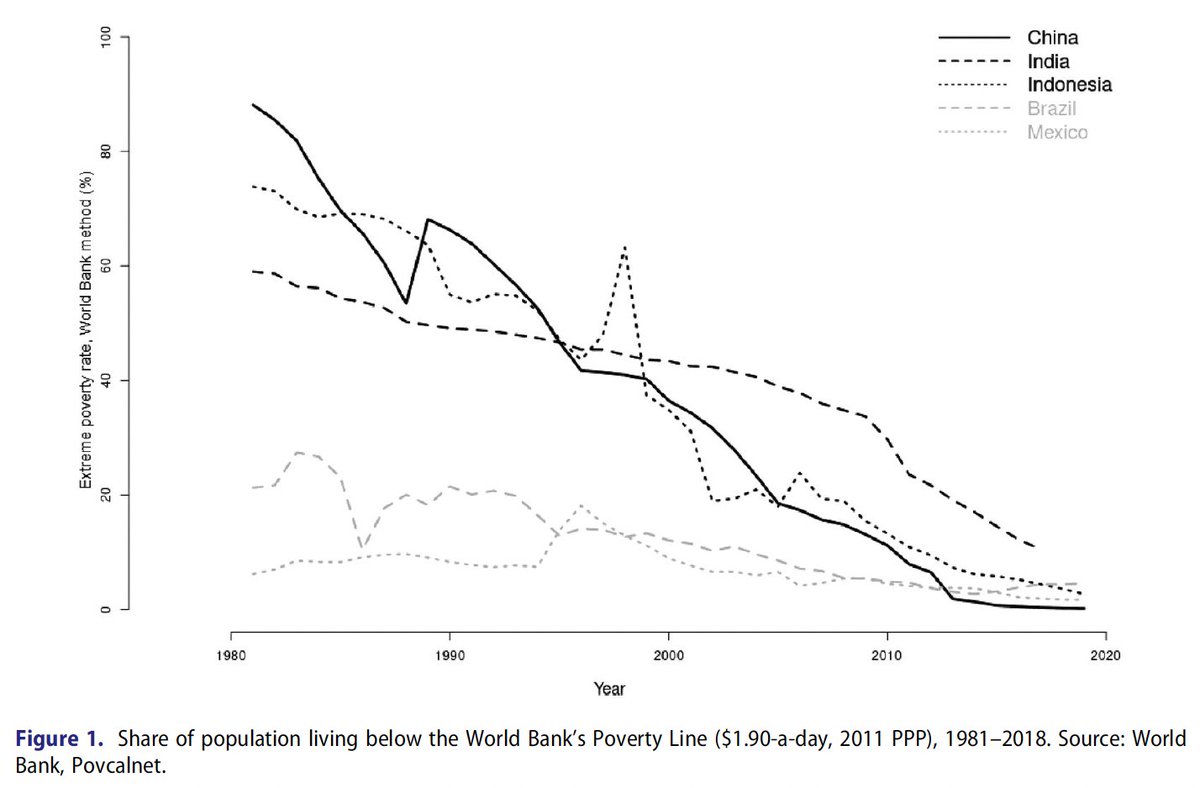

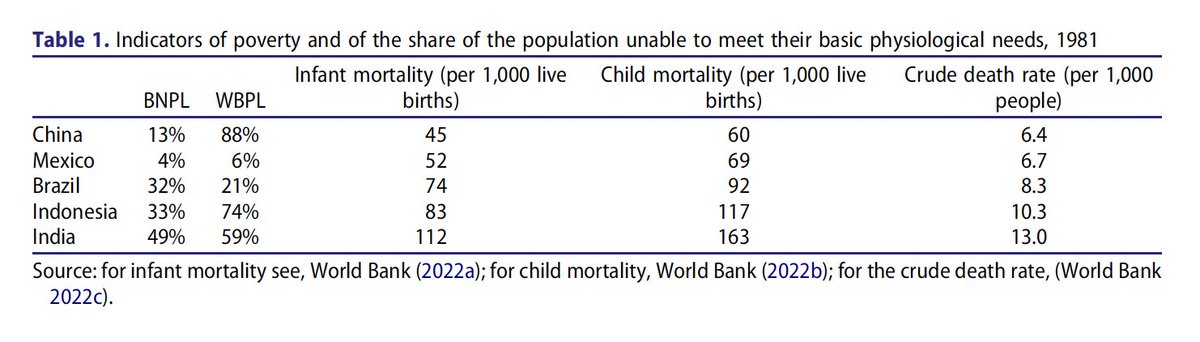

But there's a problem. For more than a decade the World Bank's method has been criticised for ignoring variations in the cost of basic needs (food, clothing, fuel, shelter). Basically, the WB poverty data does not tell us whether people can actually access necessary goods.

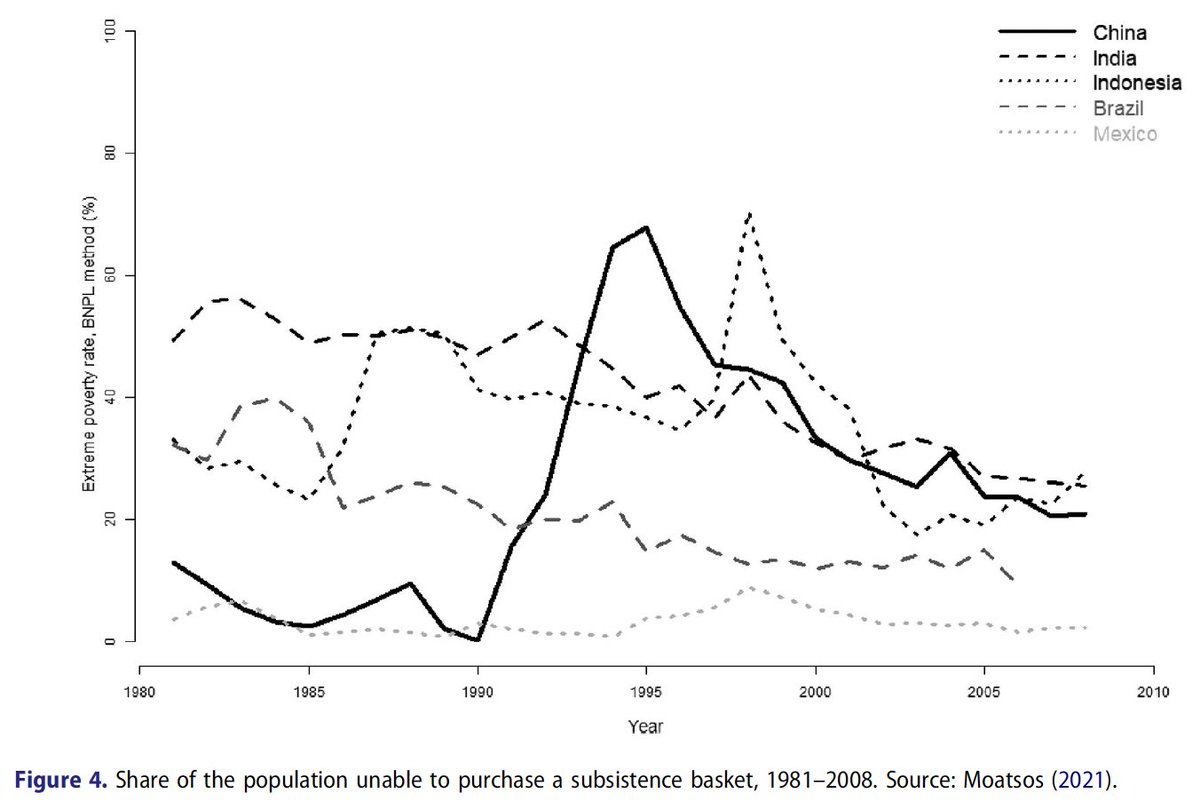

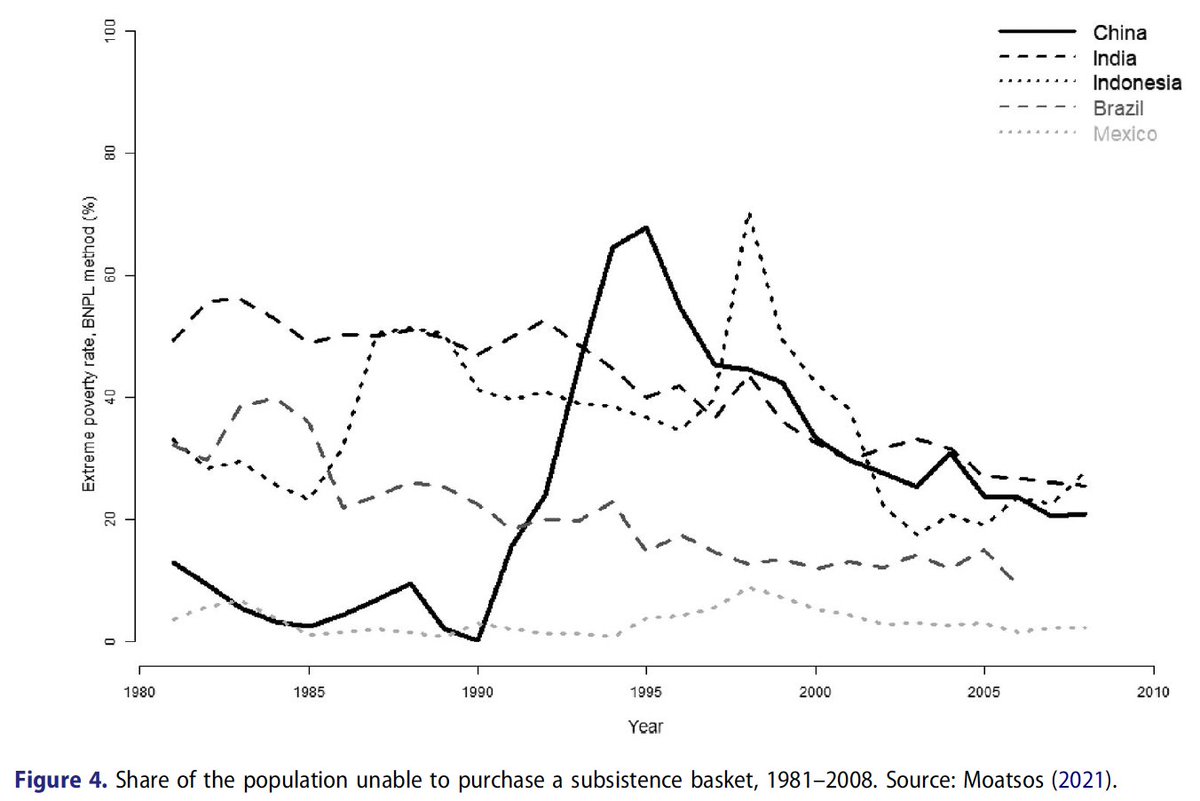

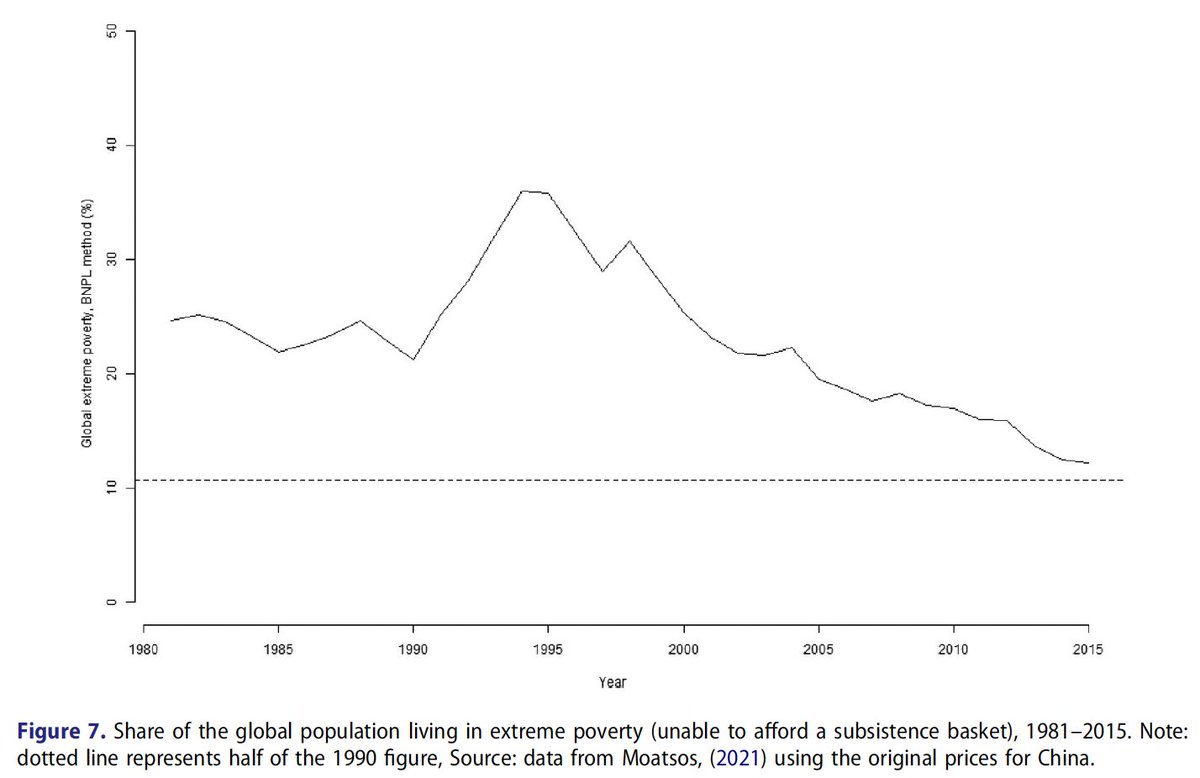

In recent years, scholars have developed a more empirically robust approach, which measures people's income against the cost of basic needs. The OECD published data from 1981-2008 (they have other years too, but not based on direct data; see footnote 2).

What does it show?

What does it show?

Not only China. Market liberalization (quite often imposed through WB/IMF structural adjustment programmes) caused extreme poverty to worsen in many other countries during this period too.

Thankfully, China has gradually recovered from this crisis. Real data only goes to 2008, but Moatsos credibly indicates the poverty rate was down to 5% by 2018, as the labour movement gains strength and as Xi's anti-poverty programmes deliver progress.

What can we learn from all this? Well, public provisioning systems (and price controls) can be *very* effective at preventing poverty and improving social outcomes. Especially in developing countries. This enabled China to outperform much richer nations.

But note that the poverty line here is focused on basic needs. Clearly China of the 1980s needed to increase industrial production to deliver higher-order living standards! We argue this could have been done without the capitalist reforms, thus preventing quite a lot of misery.

There's much more to this paper and I hope it will answer all the questions that may arise. See also our discussion of limitations. It's open-access and available here: tandfonline.com

Loading suggestions...