Wall Street loves leveraged buyouts. So much so, that a mountain of 'hung' LBO debt now threatens to blow up right in their face.

But what is an LBO and how are they hung?

Time for a debt 🧵👇

But what is an LBO and how are they hung?

Time for a debt 🧵👇

You may remember the term leveraged buyout or LBO from the good ol' Gordon Gecko days of 1980’s Wall Street

If not, or if you’re wondering how those go-go days matter today, let’s take a few minutes to walk through it all nice and easy.

If not, or if you’re wondering how those go-go days matter today, let’s take a few minutes to walk through it all nice and easy.

🎯 What’s an LBO?

Remember in the movie Wall Street, when Michael Douglas playing Gordon Gekko stands up at the annual meeting of Teldar Paper, and gives his 'Greed is Good' speech?

Here's a short video clip as a reminder: youtube.com

Remember in the movie Wall Street, when Michael Douglas playing Gordon Gekko stands up at the annual meeting of Teldar Paper, and gives his 'Greed is Good' speech?

Here's a short video clip as a reminder: youtube.com

If you don’t recall the fictional Teldar Paper circumstances or somehow haven’t yet seen this classic finance movie (highly, highly recommended BTW), I’ll give you the TL;DR

What Gekko is saying, or rather doing, here is simple.

What Gekko is saying, or rather doing, here is simple.

Gekko is making his case for a hostile takeover of the company, and to do so, he needs two things: the money and the votes

The money comes from the bankers

The votes come from the shareholders

The money comes from the bankers

The votes come from the shareholders

Here, Gekko warns them, saying that the value of their stock will continue to bleed at the hands of Teldar's 'bureaucrat' executives

and instead, they should vote in favor of his buyout offer and make a little money off the takeover premium

After all, 'greed is good'.

and instead, they should vote in favor of his buyout offer and make a little money off the takeover premium

After all, 'greed is good'.

The second group of people that Gekko must convince is the bankers

This is because in order to buy all of Teldar paper’s stock, Gekko has to borrow a massive amount of money to do it

This is called a Leveraged Buy Out. or LBO.

This is because in order to buy all of Teldar paper’s stock, Gekko has to borrow a massive amount of money to do it

This is called a Leveraged Buy Out. or LBO.

While not explicitly shown, the scene implies Gekko will fire the 33 vice presidents who do little more than 'shuffle paper between themselves’, thereby cutting costs, and 'return the company profitability again'

The shareholders will be 'helping America' if they vote yes.

The shareholders will be 'helping America' if they vote yes.

To do this, Gekko will borrow a load of money from bankers, cut costs, make the company profitable again, and in turn, make those bankers a nice sum of money in both transaction fees and high-interest debt.

Boo-ya.

Boo-ya.

Sound familiar?

Gekko rhymes with Musk, and Teldar rhymes with…Twitter?

We’ll get to that, but first a brief history of the LBO and where we stand today.

Gekko rhymes with Musk, and Teldar rhymes with…Twitter?

We’ll get to that, but first a brief history of the LBO and where we stand today.

🔍 History of LBOs

The movie Wall Street was loosely modeled after a few hedge funds and LBO barons of the 80’s, like Carl Icahn and Ronald Perelman

This wave of LBOs was started by Michael Milken, a young aggressive banker at Drexel Burnham.

The movie Wall Street was loosely modeled after a few hedge funds and LBO barons of the 80’s, like Carl Icahn and Ronald Perelman

This wave of LBOs was started by Michael Milken, a young aggressive banker at Drexel Burnham.

Milken created the market for high interest / high risk bonds which are now commonly referred to as junk bonds

Massive buyouts of TWA, Revlon, and RJR Nabisco are a few examples of gargantuan (at the time) takeovers using enormous amounts of leverage.

Massive buyouts of TWA, Revlon, and RJR Nabisco are a few examples of gargantuan (at the time) takeovers using enormous amounts of leverage.

The idea is to borrow tons of money, take over a company, then cut costs through layoffs or selling divisions or assets of the company

This helps pay off the massive debt quickly

So, why would a banker do this deal? Why they lend all that money for something so risky?

This helps pay off the massive debt quickly

So, why would a banker do this deal? Why they lend all that money for something so risky?

It’s pretty simple really: Fees

To demonstrate, we will go back to Wall Street and Gekko, this time entering the boardroom where Gekko’s investment officer is negotiating with bankers and attorneys to get them to agree to lend him enough money to take over Bluestar Airlines.

To demonstrate, we will go back to Wall Street and Gekko, this time entering the boardroom where Gekko’s investment officer is negotiating with bankers and attorneys to get them to agree to lend him enough money to take over Bluestar Airlines.

The play here is Gekko wants to buy Bluestar and raid it’s corporate treasury.

How:

• Gekko gets the bankers to loan him enough money to buy the whole company

• The bankers convince other bankers and investors to then buy the debt from them (the main bankers act as agents)

How:

• Gekko gets the bankers to loan him enough money to buy the whole company

• The bankers convince other bankers and investors to then buy the debt from them (the main bankers act as agents)

• The main bankers then get paid a transaction fee (typically 2 to 3%) on the whole pile of debt

• Gekko buys the company and immediately liquidates the hangers and the planes

• Gekko buys the company and immediately liquidates the hangers and the planes

• Gekko pays off the money that the banks loaned to him (the debt)

• He keeps Bluestar’s overfunded pension (the treasury)

• Gekko makes a $60-70 million profit on the deal

• He keeps Bluestar’s overfunded pension (the treasury)

• Gekko makes a $60-70 million profit on the deal

Not bad for a month’s work, as they said in the movie

Though Bud Fox scuttles this plan, those are the basics of how it would go if Gekko succeeded in the LBO

Ok, but where’s the risk, then, you may ask?

Though Bud Fox scuttles this plan, those are the basics of how it would go if Gekko succeeded in the LBO

Ok, but where’s the risk, then, you may ask?

Good question, and it has to do with volatility of interest rates and investor appetite for risk

Aha! Now you may see the connection to today

Let’s dig into that next...

Aha! Now you may see the connection to today

Let’s dig into that next...

✍️ Today’s LBO Market

Today, we're obviously experiencing interest rate volatility

Rates are moving around all over the map as the Fed fumbles with both their policy and their messaging to the public about said policy

Today, we're obviously experiencing interest rate volatility

Rates are moving around all over the map as the Fed fumbles with both their policy and their messaging to the public about said policy

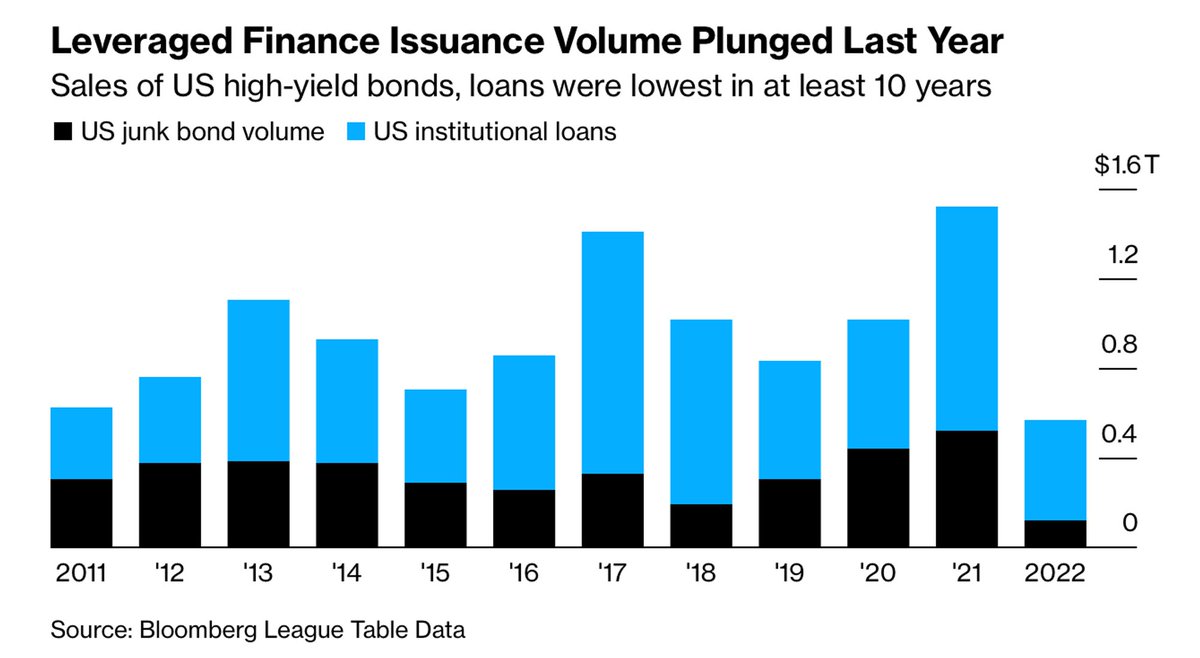

That said, up until last spring, bankers still had an appetite for high yield and junk bonds

After all, they enjoyed the fees for doing transactions and had little problem laying off the risky debt to other banks and investors

After all, they enjoyed the fees for doing transactions and had little problem laying off the risky debt to other banks and investors

And so now, after providing all that debt to unprofitable companies and LBOs, big banks are struggling to sell that debt to investors or other banks

It’s stuck on their books

Hung debt.

It’s stuck on their books

Hung debt.

See, bankers buy the debt in the LBO or from the struggling company with hopes of re-selling that debt to other banks or institutional investors

But sometimes the market dries up, and the facilitating banks are left with it on their own books

They're 'hung with the debt'.

But sometimes the market dries up, and the facilitating banks are left with it on their own books

They're 'hung with the debt'.

Question is, do the banks pull through here unscathed,

or do we have what we call a credit event looming on the horizon?

or do we have what we call a credit event looming on the horizon?

🧠 Does it all blow up?

The main problem:

As rates rise, debt that is on these banks’ books becomes worth *less*

This is both because of simple math (rates go up, bond prices go down) and because of the implications of higher rates

The main problem:

As rates rise, debt that is on these banks’ books becomes worth *less*

This is both because of simple math (rates go up, bond prices go down) and because of the implications of higher rates

Higher rates means higher borrowing costs for consumers and companies

Higher borrowing costs means less activity from consumers and lower profits for companies

Higher borrowing costs means less activity from consumers and lower profits for companies

Lower profits or losses means higher risk

Higher risk means investors demand higher ROIs (returns on investments) or interest on loans and debt

A self-perpetuating problem.

Higher risk means investors demand higher ROIs (returns on investments) or interest on loans and debt

A self-perpetuating problem.

In other words, the days of easy and free money are pretty much over right now

Look at Japan: the last bastion of free money is free no more, rates are rising there, along with the cost of capital globally.

Look at Japan: the last bastion of free money is free no more, rates are rising there, along with the cost of capital globally.

In a game of musical chairs, Morgan Stanley has been left standing without a seat, hung with ~$1B of losses themselves, nobody to dump it on

While funds are reportedly willing to pay 60c on the dollar for the debt, bankers have refused to sell below 70c.

While funds are reportedly willing to pay 60c on the dollar for the debt, bankers have refused to sell below 70c.

A stalemate of sorts

And the bankers are playing a game of chicken, betting that either interest rates stop going up or Elon succeeds at turning a profit at Twitter soon

Either way, the appetite for risk from institutional investors must increase, or the entire market dries up

And the bankers are playing a game of chicken, betting that either interest rates stop going up or Elon succeeds at turning a profit at Twitter soon

Either way, the appetite for risk from institutional investors must increase, or the entire market dries up

And so, with every basis point the Fed tightens as the US heads into a recession, the probability of a credit event rises exponentially

At some point, a large company or bank runs into a liquidity issue and will need to borrow money to keep it going

At some point, a large company or bank runs into a liquidity issue and will need to borrow money to keep it going

But with investor and bank appetite for risk evaporating, the money…the help…may not be there

And the risk of a company blowing up raises the risk of a bank blowing up, thereby raising the risk of multiple banks blowing up, thereby 'requiring' another government-led bailout.

And the risk of a company blowing up raises the risk of a bank blowing up, thereby raising the risk of multiple banks blowing up, thereby 'requiring' another government-led bailout.

Credit + Leverage + Illiquidity → Contagion

These are all closely related words. Ones that should put the fear of God into any banker who is currently hung with billions of dollars of leveraged debt

Especially if it is unsecured and Twitters’.

These are all closely related words. Ones that should put the fear of God into any banker who is currently hung with billions of dollars of leveraged debt

Especially if it is unsecured and Twitters’.

This thread is a summary of a recent Informationist Newsletter. If you enjoyed it, make sure to:

1. Follow @jameslavish to see more investment related content

2. Subscribe to The Informationist to learn one simplified concept weekly: jameslavish.substack.com

1. Follow @jameslavish to see more investment related content

2. Subscribe to The Informationist to learn one simplified concept weekly: jameslavish.substack.com

Loading suggestions...