1) Between inflation and recession:

Post-Modern Monetary Theory

Post-Modern Monetary Theory

2) AKA, "number go up".

3) I should disclaim this by saying that I have very little training in macroeconomics, and am mostly piecing this together based on a bunch of different thoughts from people much smarter than I.

Much of this is probably wrong.

Not financial advice.

Much of this is probably wrong.

Not financial advice.

5) Why?

Well, let's start with a case where printing money doesn't do _anything_, and then find the differences.

Let's say that the gov't prints $0.50 for each $1 that exists, and airdrops those dollars pro-rata on everyone; so if you had $6 before, you have $9 now.

Well, let's start with a case where printing money doesn't do _anything_, and then find the differences.

Let's say that the gov't prints $0.50 for each $1 that exists, and airdrops those dollars pro-rata on everyone; so if you had $6 before, you have $9 now.

6) This doesn't accomplish anything, really: it's just a 1.5-for-1 stock split in the US Dollar. If a loaf of bread cost $4 before, it costs $6 now; everyone has 1.5x as many USD, and all prices go up 1.5x.

7) So what does printing money do?

Well, let's say that, instead of giving out the 0.5x new money pro-rata, you give it out to some public goods project, or you give each person an equal amount (rather than pro-rata to their old wealth).

Now, there's _real_ inflation.

Well, let's say that, instead of giving out the 0.5x new money pro-rata, you give it out to some public goods project, or you give each person an equal amount (rather than pro-rata to their old wealth).

Now, there's _real_ inflation.

8) Why might you want that?

Well, it's basically a tax on USD holdings; it disincentives keeping your wealth in dollars.

And so it incentivizes investing, or doing commerce.

Maybe you just think people are scared or risk-averse, especially during a recession.

Well, it's basically a tax on USD holdings; it disincentives keeping your wealth in dollars.

And so it incentivizes investing, or doing commerce.

Maybe you just think people are scared or risk-averse, especially during a recession.

9) So you can use inflation to counter-balance fear in markets.

But for that to work, *someone* has to end up holding the dollars, after the commerce is done. Who is that holding the bag?

Maybe it's foreign governments, and this is the tax on them getting your stability.

But for that to work, *someone* has to end up holding the dollars, after the commerce is done. Who is that holding the bag?

Maybe it's foreign governments, and this is the tax on them getting your stability.

10) Maybe it's people cashing out.

Alice founds a company, XYZ. She runs XYZ for a while, all her wealth is in XYZ, and she wins to inflation.

After she's made a lot of money, she sells it to investors, and holds USD. It decays a bit, but she secures a comfortable life.

Alice founds a company, XYZ. She runs XYZ for a while, all her wealth is in XYZ, and she wins to inflation.

After she's made a lot of money, she sells it to investors, and holds USD. It decays a bit, but she secures a comfortable life.

11) Finally: let's say that Bob wants to buy a widget from Alice.

It costs Alice $5 to make, and it's worth $7 to Bob. In theory, Alice should sell it to Bob. But Alice wants to make profit! So she might charge $8, and then the economy isn't efficient.

It costs Alice $5 to make, and it's worth $7 to Bob. In theory, Alice should sell it to Bob. But Alice wants to make profit! So she might charge $8, and then the economy isn't efficient.

12) By incentivizing transactions and investing over holding USD, maybe inflation can cause some positive sum transactions to "cross the bid ask spread", so to speak.

13) Ok, so there are some reasons that moderate inflation can be good.

By essentially disincentivizing holding fiat, it can compensate for the risk and spreads involved in commerce, causing positive sum trades to happen.

By essentially disincentivizing holding fiat, it can compensate for the risk and spreads involved in commerce, causing positive sum trades to happen.

14) It makes sense, then, that monetary supply started increasing more quickly in 2008 and 2020: the recession and COVID, respectively, increased fear in the markets, and so maybe some quantitative easing was useful to compensate.

How much, though?

How much, though?

15) Well, I don't know for sure! But I think a reasonable heuristic is:

You want it to make sense for companies to invest in their operations. If the typical company has a P/E of ~20, then it's taking on risk to grow capital at 5%/year.

So inflation had better be < 5%/year!

You want it to make sense for companies to invest in their operations. If the typical company has a P/E of ~20, then it's taking on risk to grow capital at 5%/year.

So inflation had better be < 5%/year!

16) And, in fact, since 2000, inflation has averaged ~2.3%/year.

So far, everything looks reasonable: the gov't keeps printing $, it causes ~2.5% inflation, it offsets the risk of investing, and scales up during recessions when risk is the highest.

So what's the worry?

So far, everything looks reasonable: the gov't keeps printing $, it causes ~2.5% inflation, it offsets the risk of investing, and scales up during recessions when risk is the highest.

So what's the worry?

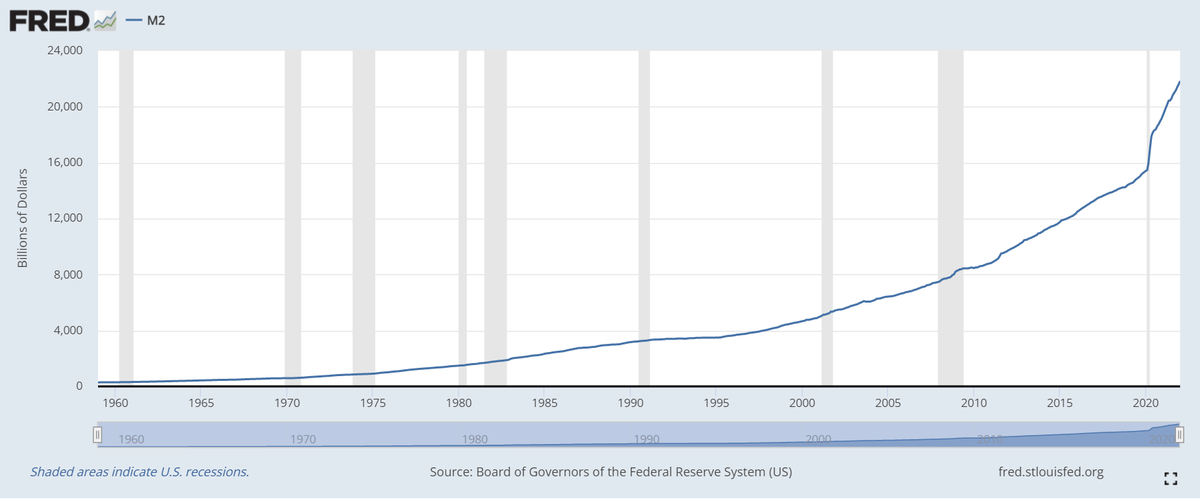

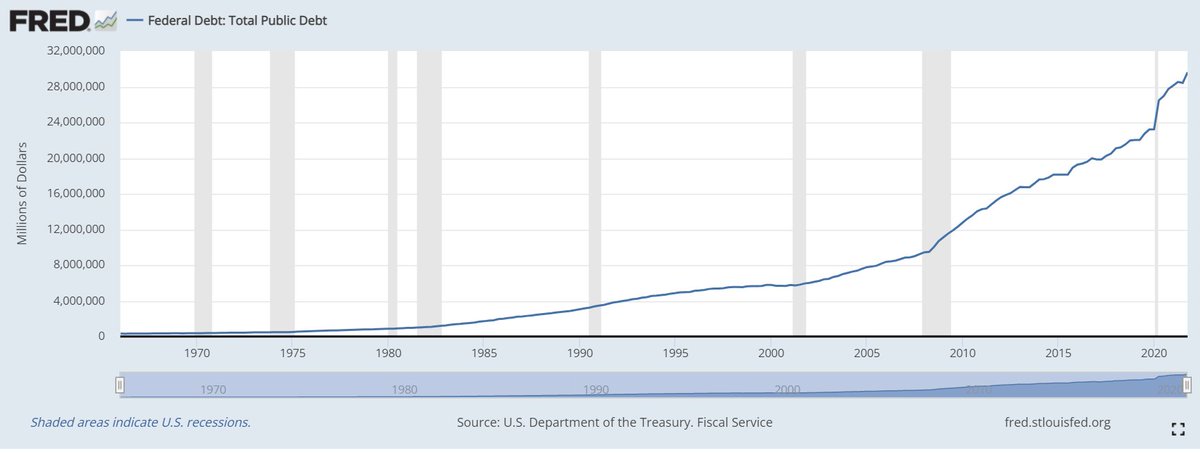

17) Well, let's return to the rate of monetary supply increase.

M2 has been about $20T. Also, recently monetary supply/debt/etc. have been increasing at about $3.5b/year--so roughly 17%/year.

That's up from 10% over the past decade, and 3% over the 2000's.

Uh oh?

M2 has been about $20T. Also, recently monetary supply/debt/etc. have been increasing at about $3.5b/year--so roughly 17%/year.

That's up from 10% over the past decade, and 3% over the 2000's.

Uh oh?

18) And so we reach the first deeply weird fact about the modern economy: that monetary supply has been increasing at about 5x the rate of inflation.

Why? Which metric is correct?

Has QE been roughly correctly targeted, or massively over-done?

Why? Which metric is correct?

Has QE been roughly correctly targeted, or massively over-done?

19) Well, inflation is measured via CPI.

CPI is bread, and gym memberships, and clothing, and tuition.

CPI has only increased a few % per year recently.

But not everything is part of CPI. Is there a bias here? Is CPI measuring the right thing?

CPI is bread, and gym memberships, and clothing, and tuition.

CPI has only increased a few % per year recently.

But not everything is part of CPI. Is there a bias here? Is CPI measuring the right thing?

20) I don't know what "right" means here.

Let's try again: is it correctly measuring the impact of monetary policy?

Well, over the past decade, there's been a huge increase in the amount of money in circulation.

Where did that money go?

Let's try again: is it correctly measuring the impact of monetary policy?

Well, over the past decade, there's been a huge increase in the amount of money in circulation.

Where did that money go?

21) A few secular trends:

a) the world becomes digital

b) the world becomes financial

c) borrowing becomes way easier

(a) means that the titans of web2 made a lot of money (e.g. @elonmusk).

(b) means that the titans of finance made a lot of money (e.g. Buffet).

a) the world becomes digital

b) the world becomes financial

c) borrowing becomes way easier

(a) means that the titans of web2 made a lot of money (e.g. @elonmusk).

(b) means that the titans of finance made a lot of money (e.g. Buffet).

22) (c) means that (a) and (b) can borrow against their equity (that they either created or invested in), increasing the liquid capital they have.

All three of these point in the same direction:

the richest people from 2022 are worth a lot more than the richest from 2007.

All three of these point in the same direction:

the richest people from 2022 are worth a lot more than the richest from 2007.

23) Some of this is the rich getting richer; some is _new_ people climbing higher than anyone from 2007.

But, one way or another, it's happening:

forbes.com

The richest people are worth 3x as much as 2007's richest.

But _median_ income has only grown ~33%.

But, one way or another, it's happening:

forbes.com

The richest people are worth 3x as much as 2007's richest.

But _median_ income has only grown ~33%.

24) And, the thing is--what drives CPI?

Well, CPI is, basically, bread.

Elon Musk is worth roughly one million times as much as the median American.

@elonmusk does not eat one million loaves of bread per day.

So CPI tracks the median American more so than the average one.

Well, CPI is, basically, bread.

Elon Musk is worth roughly one million times as much as the median American.

@elonmusk does not eat one million loaves of bread per day.

So CPI tracks the median American more so than the average one.

25) And, in fact, CPI inflation has been roughly in line with median wage growth!

So, ok, if @elonmusk doesn't buy $1m of bread, what *does* he buy $1m of?

So, ok, if @elonmusk doesn't buy $1m of bread, what *does* he buy $1m of?

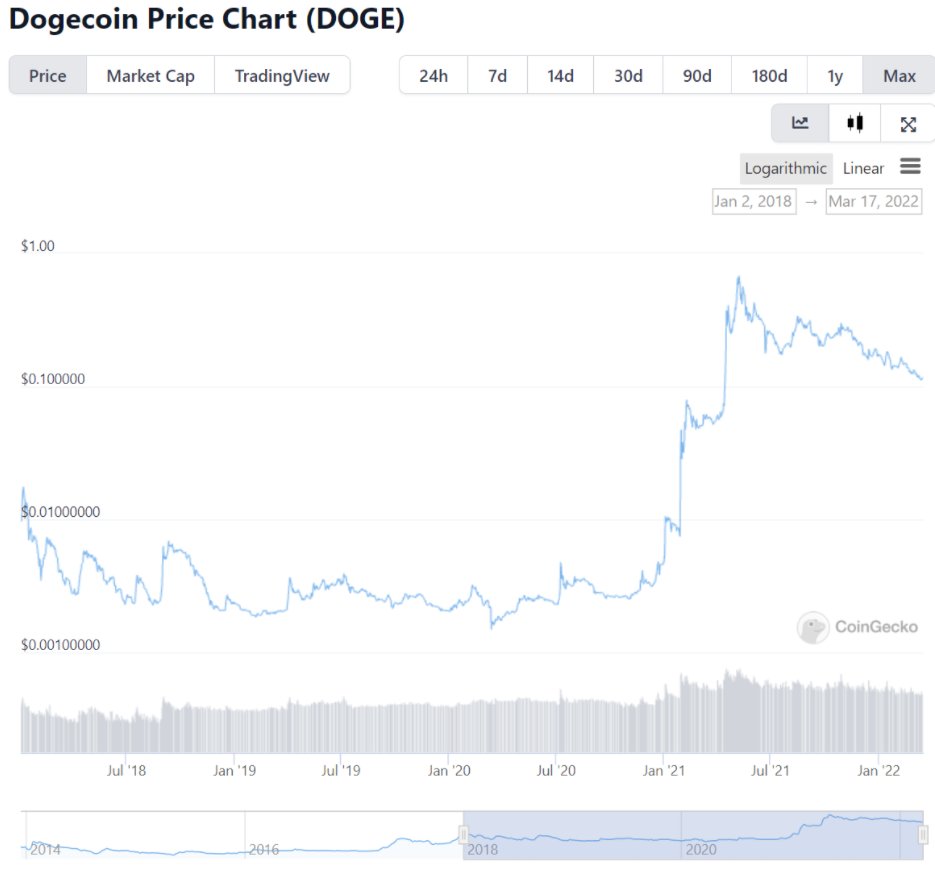

27) In particular, given the amount of wealth that has gone towards creating the richest in history, the assets whose prices have appreciated–the place that the 17% annual monetary supply increases have gone–are assets that a single person could spend millions of dollars on.

28) So yes, cryptocurrencies. But also stocks, and high end housing, and private planes, and art, and NFTs, and sports teams (which, really, are themselves NFTs).

In general, things you can invest in have gone up a lot. And things with limited supply. As have Giffen Goods.

In general, things you can invest in have gone up a lot. And things with limited supply. As have Giffen Goods.

29) (An interesting aside: when a ton of capital flows into those assets, and prices appreciate, then the investors make money. Also capital is cheap, so they can borrow or raise, and then buy more, and then prices go up more, and then...)

30) So, ok, CPI inflation has been somewhat stable, but other measures of price inflation have been huge, because CPI is in line with median wage growth and markets are in line with invested capital growth.

31) And if you average those out, you get something closer to what the monetary growth implies: that real, true inflation has probably been closer to 17% than 2.5%.

32) And 17% is a lot.

So, in the end, I think that in some senses the straightforward answer is the correct one. The inflation has been here the whole time, hiding in plain sight.

The worry, then, is hyperinflation, devaluation of the US dollar, and serious economic impact.

So, in the end, I think that in some senses the straightforward answer is the correct one. The inflation has been here the whole time, hiding in plain sight.

The worry, then, is hyperinflation, devaluation of the US dollar, and serious economic impact.

33) Does that mean that monetary policy has been bad and reckless?

I don’t know–it’s complicated.

Because we’ve only been talking about the inflation side of monetary policy.

And, again, it’s not a coincidence that this has been the decade of QE.

I don’t know–it’s complicated.

Because we’ve only been talking about the inflation side of monetary policy.

And, again, it’s not a coincidence that this has been the decade of QE.

34) In 2008, every bank almost failed. And then in 2020, the world economy half shut down for two years.

And somehow, not only did we make it out with the financial system intact, but we made it through COVID without a recession–in fact, markets hit all-time highs!

Oh, wait.

And somehow, not only did we make it out with the financial system intact, but we made it through COVID without a recession–in fact, markets hit all-time highs!

Oh, wait.

35) I mean, partially what happened, probably, was that commerce and investment were incentivized by loose monetary policy.

And partially, the government effectively provided desperately needed bridge loans to companies that were going to have a bad few years because of COVID.

And partially, the government effectively provided desperately needed bridge loans to companies that were going to have a bad few years because of COVID.

36) And so to some extent we made a trade, as a world. We accepted higher inflation that generally makes sense, in return for weathering a huge financial storm remarkably well.

Yeah, price increases hurt, but honestly it’s way better than if you tacked 2008 on to COVID.

Yeah, price increases hurt, but honestly it’s way better than if you tacked 2008 on to COVID.

37) There’s another side to this, too, though.

“Number go up.”

See, if all you do is ‘stock split’ the US Dollar, handing everyone an extra 50%, it has no real economic impact…

…as long as everyone mentally multiplies all price charts by ⅔ after the split.

“Number go up.”

See, if all you do is ‘stock split’ the US Dollar, handing everyone an extra 50%, it has no real economic impact…

…as long as everyone mentally multiplies all price charts by ⅔ after the split.

38) But if you don’t adjust how you look at the charts, then it seems, I guess, like everything just went up 50%.

Which is bad for inflation, but great for markets?

Which is bad for inflation, but great for markets?

39) And so some of what’s happened over the last decade–and especially over the last few years–is that bad things happened (e.g. COVID) but markets went up instead of down, because we increased monetary supply.

40) And, I guess, it ‘tricked’ some of us into thinking that things were going great, because “number go up”, when really that $440 SPY buys about as much stuff today as $330 SPY bought a few years ago.

41) So what does all of this imply for the future?

Well, on the one hand, inflation–true inflation–is high. Really high. High enough that it would generally be worrying.

Does that mean markets will keep going up? Especially given that even CPI inflation is now high?

Well, on the one hand, inflation–true inflation–is high. Really high. High enough that it would generally be worrying.

Does that mean markets will keep going up? Especially given that even CPI inflation is now high?

42) Maybe. But maybe not. Because to some extent, that should already be priced in to “efficient” markets.

As soon as the world realized what was going to happen to policy because of COVID, prices should have adjusted to the full increase that all future QE would bring.

As soon as the world realized what was going to happen to policy because of COVID, prices should have adjusted to the full increase that all future QE would bring.

43) CPI increasing this year doesn’t make markets go up more: markets already knew that the monetary supply had increased, and didn’t have to wait for CPI to move.

44) Instead, CPI increasing this year had the effect of increasing political pressure to reduce inflation by tightening monetary policy. So increased inflation indicators sometimes lead to decreased inflation, because of policy reactions.

45) So I don’t know what this means going forward.

On the one hand, there are real signs of tightening policy for the first time in a while.

On the other hand, even the proposed rate hikes are a lot less than true inflation probably is, barely making a dent in real rates.

On the one hand, there are real signs of tightening policy for the first time in a while.

On the other hand, even the proposed rate hikes are a lot less than true inflation probably is, barely making a dent in real rates.

46) And also, there’s a war going on now, on top of COVID; there will be pressure to prevent markets from crashing, which means, well, you know…

47) So in the end–I don’t know what will happen going forward.

I wish I were smart enough to see the future, rather than just the past.

But I guess my main takeaways from MMT are:

a) It probably lead to significant, serious inflation

b) Also it probably prevented a recession

I wish I were smart enough to see the future, rather than just the past.

But I guess my main takeaways from MMT are:

a) It probably lead to significant, serious inflation

b) Also it probably prevented a recession

48) Those are, sometimes, two sides of the same coin.

And, also:

c) QE → number go up → easy to get financing → number go up → easy to get financing → …

And, also:

c) QE → number go up → easy to get financing → number go up → easy to get financing → …

49) We have, accidentally, been exploring Post-Modern Monetary Theory as a society.

A system designed so that numbers mostly just go up and up and up, as they mean less and less and less.

A system designed so that numbers mostly just go up and up and up, as they mean less and less and less.

50) Thus, BTC. And oil, and nickel, and SPY, and houses, and art, and bonds, and VC fund sizes, and private markets, and pretty much everything marked to market.

Loading suggestions...