Many Liverpool fans cannot understand why their club seems unwilling to buy players. Surely they should be awash with cash after winning the Champions League and then the Premier League? This thread looks at where the money has gone and suggests why they are not buying #LFC

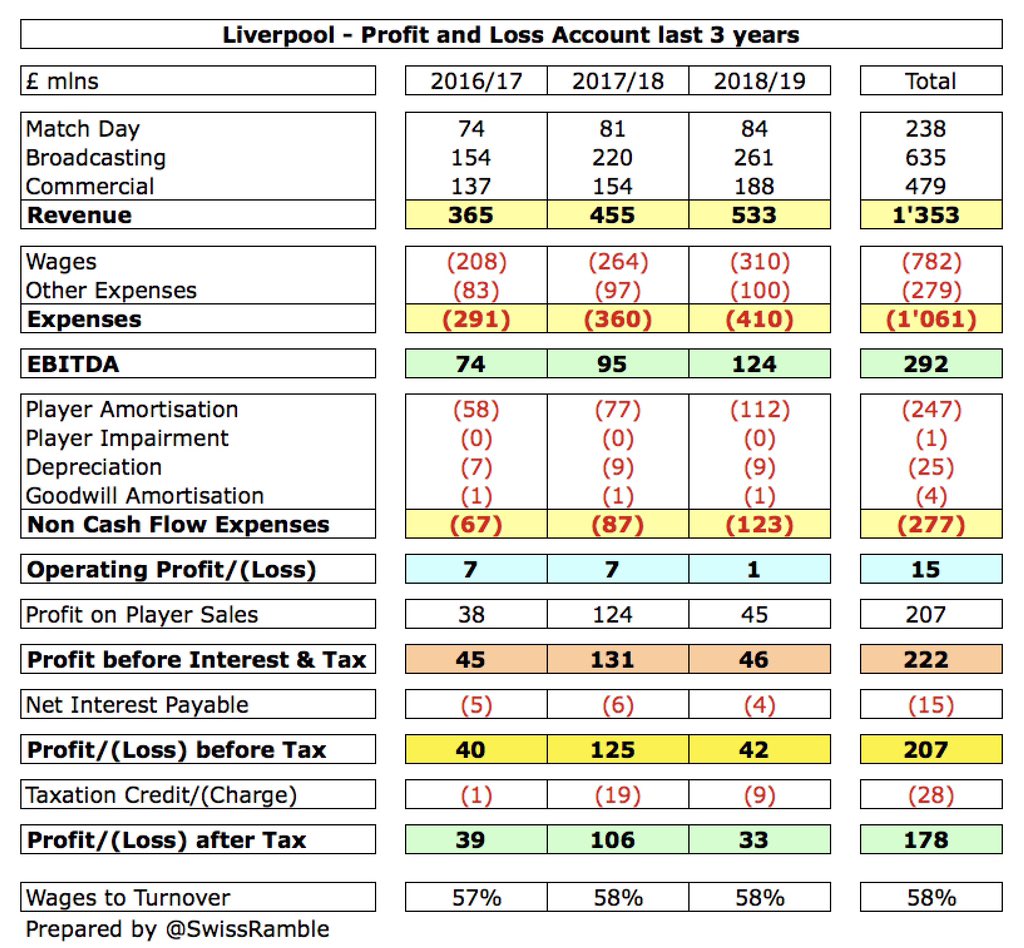

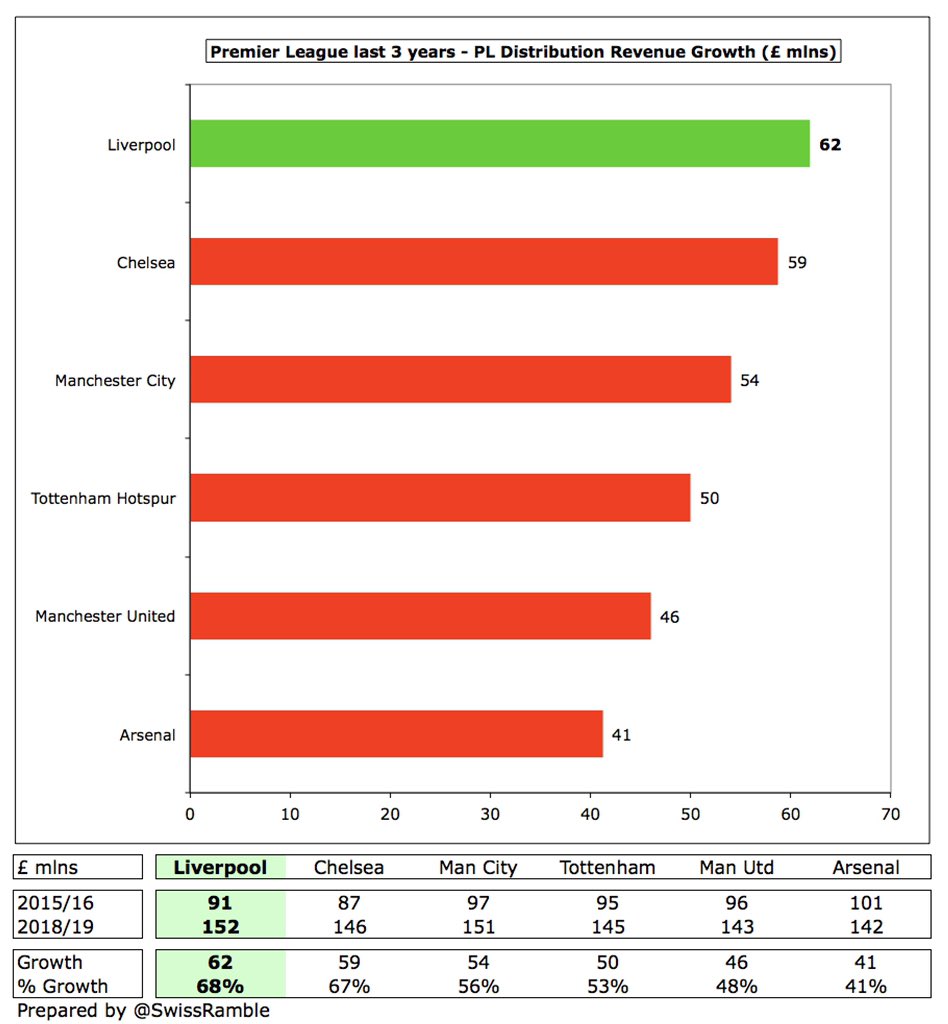

This is somewhat puzzling, given that #LFC have been highly profitable in recent years, so let’s look at what is behind their revenue growth and the impact on the bottom line. As well as the last published accounts (2018/19), we will take a broader view of the last 3 years.

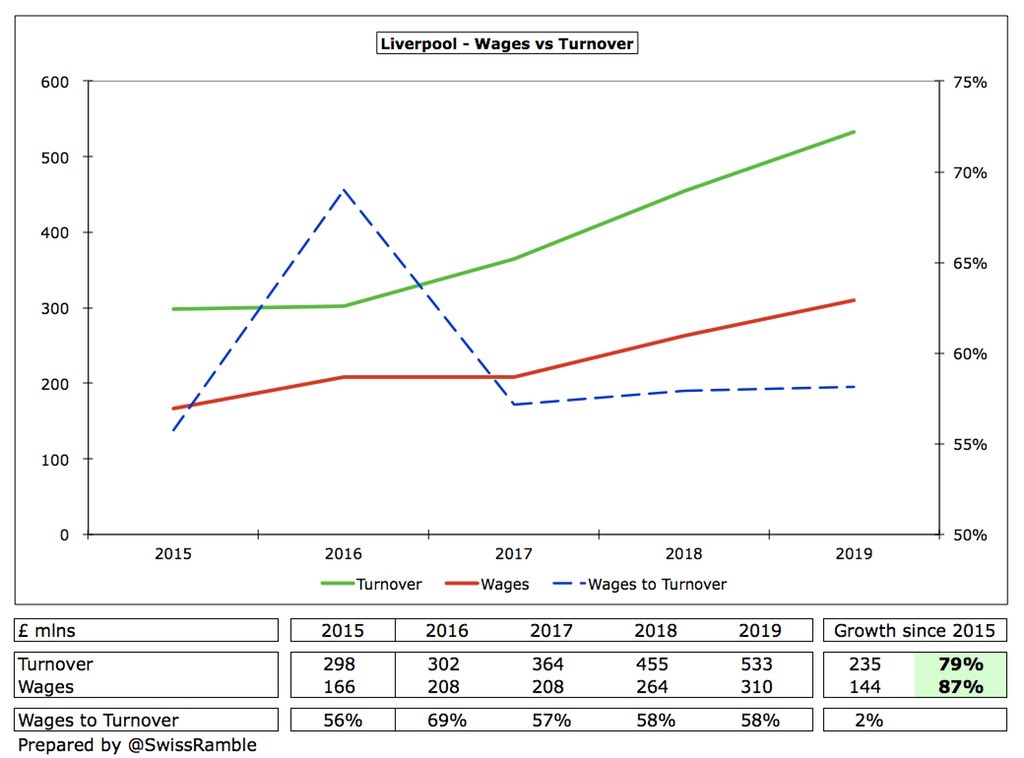

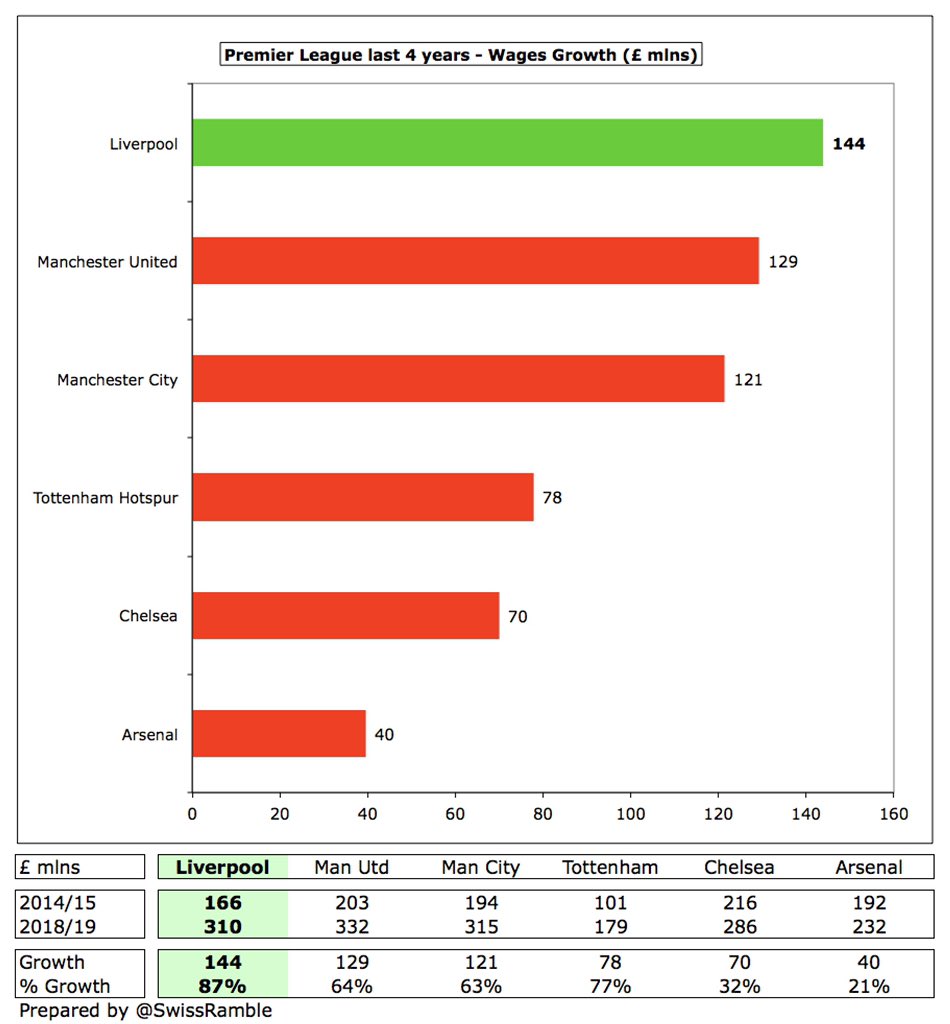

However, here’s the thing. Much of the revenue growth has been eaten up by higher costs. In fact. Since 2015 #LFC wages have grown 87% (£144m), i.e. at a faster rate than revenue 79% (£235m), the highest in the Big 6, due to recruiting better players and higher bonus payments.

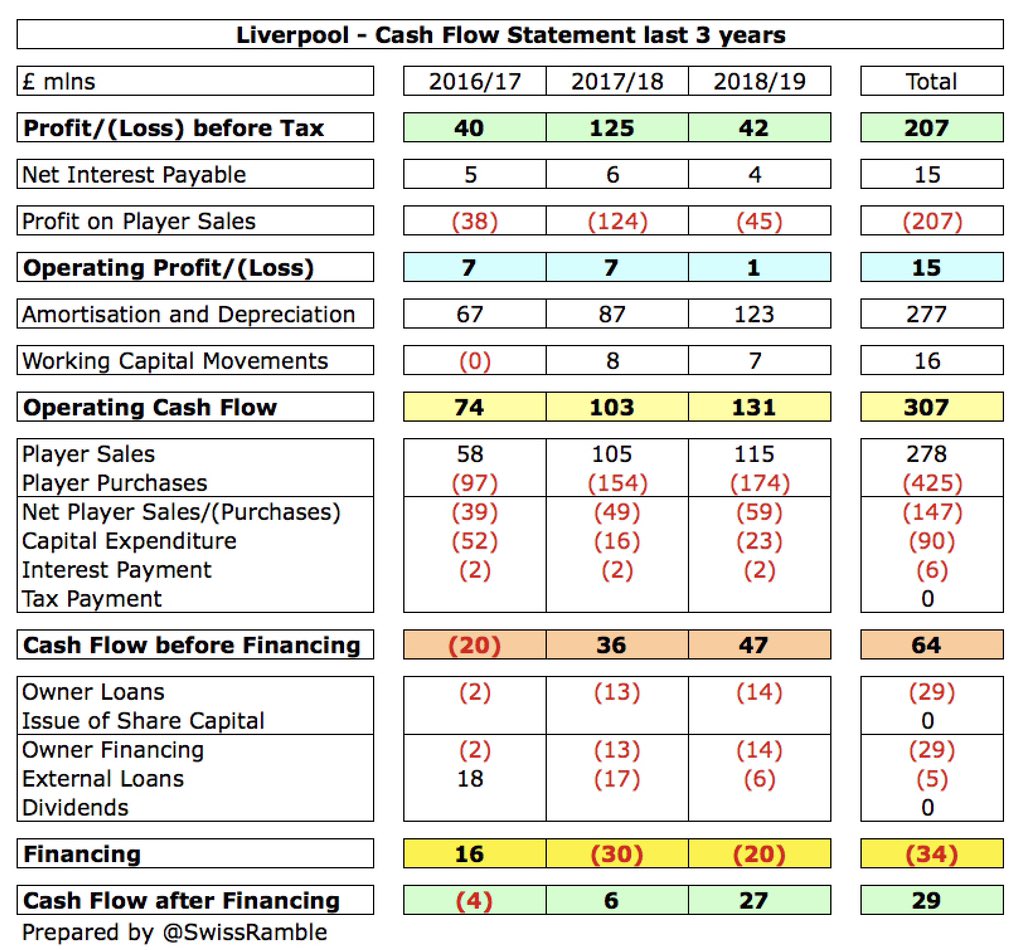

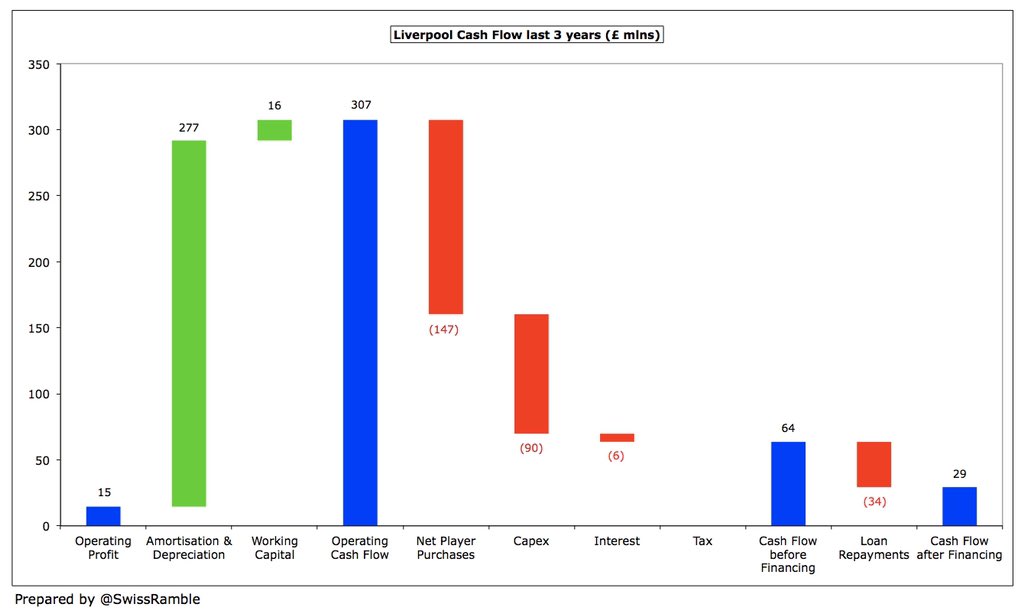

The profit and loss account does not tell the whole story, as it only shows an accounting profit, which is very different from actual cash movements. Over last 3 years #LFC had £207m profit, but only £29m net cash inflow. We shall now look at where the rest of the money has gone.

For the cash flow statement, we need to strip out the non-cash accounting entries, both for player trading, namely profit on player sales and player amortisation, and other depreciation, impairment, etc; then adjust for working capital movements.

At this stage we need to understand how football clubs account for player trading, both for purchases and sales, as the accounting treatment in the profit and loss account is quite different to the actual cash movements.

Football clubs do not fully expense transfer fees in the year a player is purchased, but instead write-off the cost evenly over the length of the player’s contract via player amortisation, while any profit made from selling players is immediately booked to the accounts.

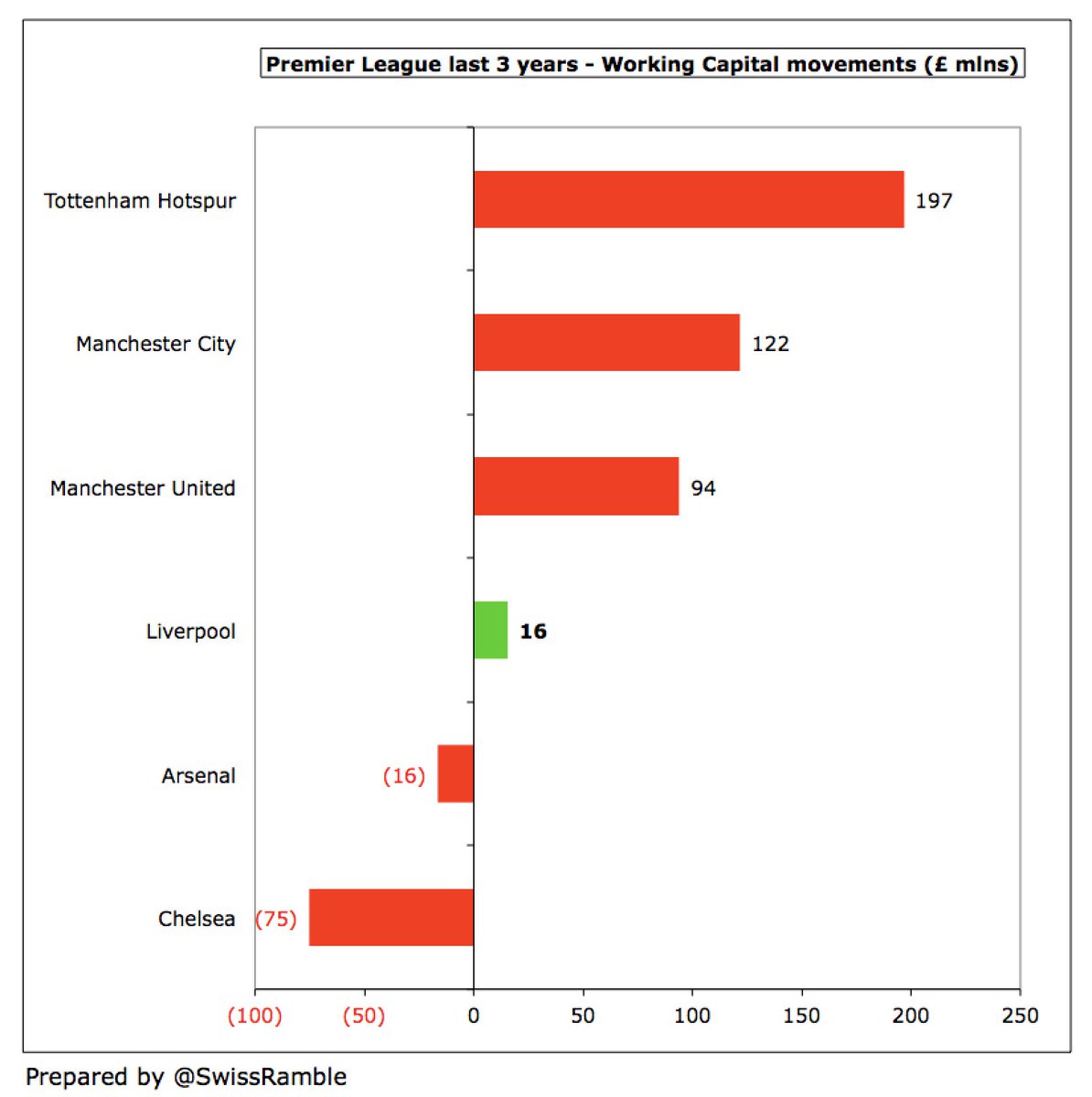

Working capital measures short-term liquidity, defined as current assets less current liabilities. Changes in working capital can cause operating cash flow to differ from net profit, as clubs book revenue and expenses when they occur instead of when cash actually changes hands.

If current liabilities increase, a club is paying its suppliers more slowly, so is holding on to cash (positive for cash flow). On the other hand, if a club’s debtors increase, this means it collected less money from customers than it recorded as revenue (negative for cash flow).

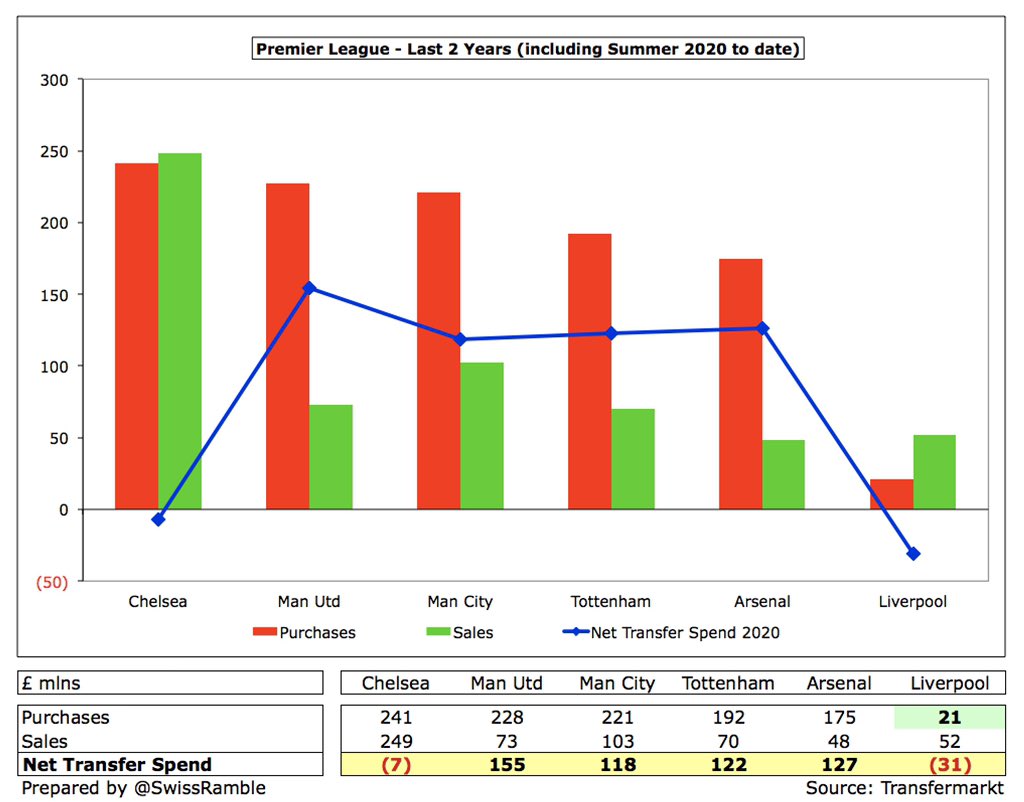

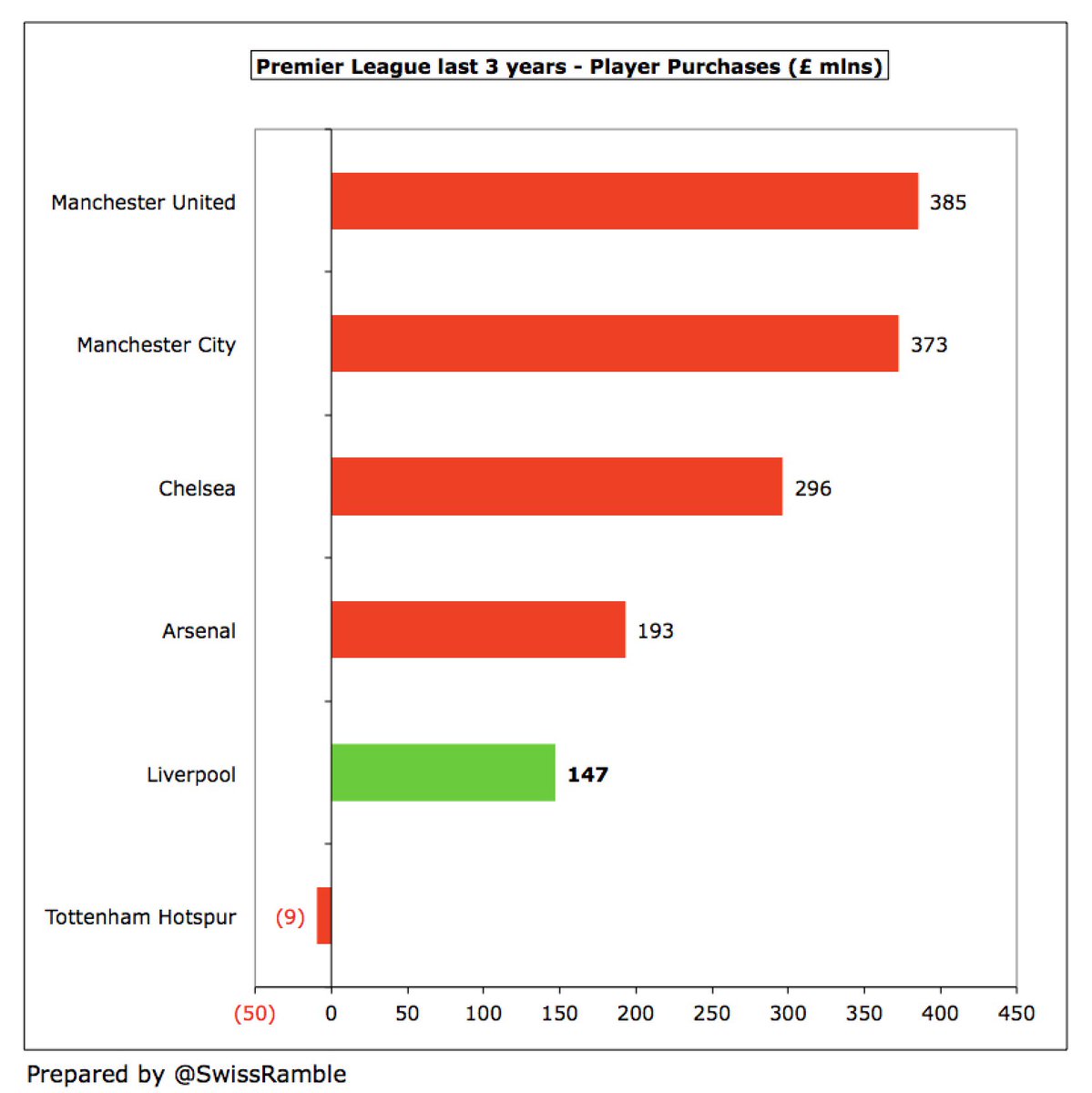

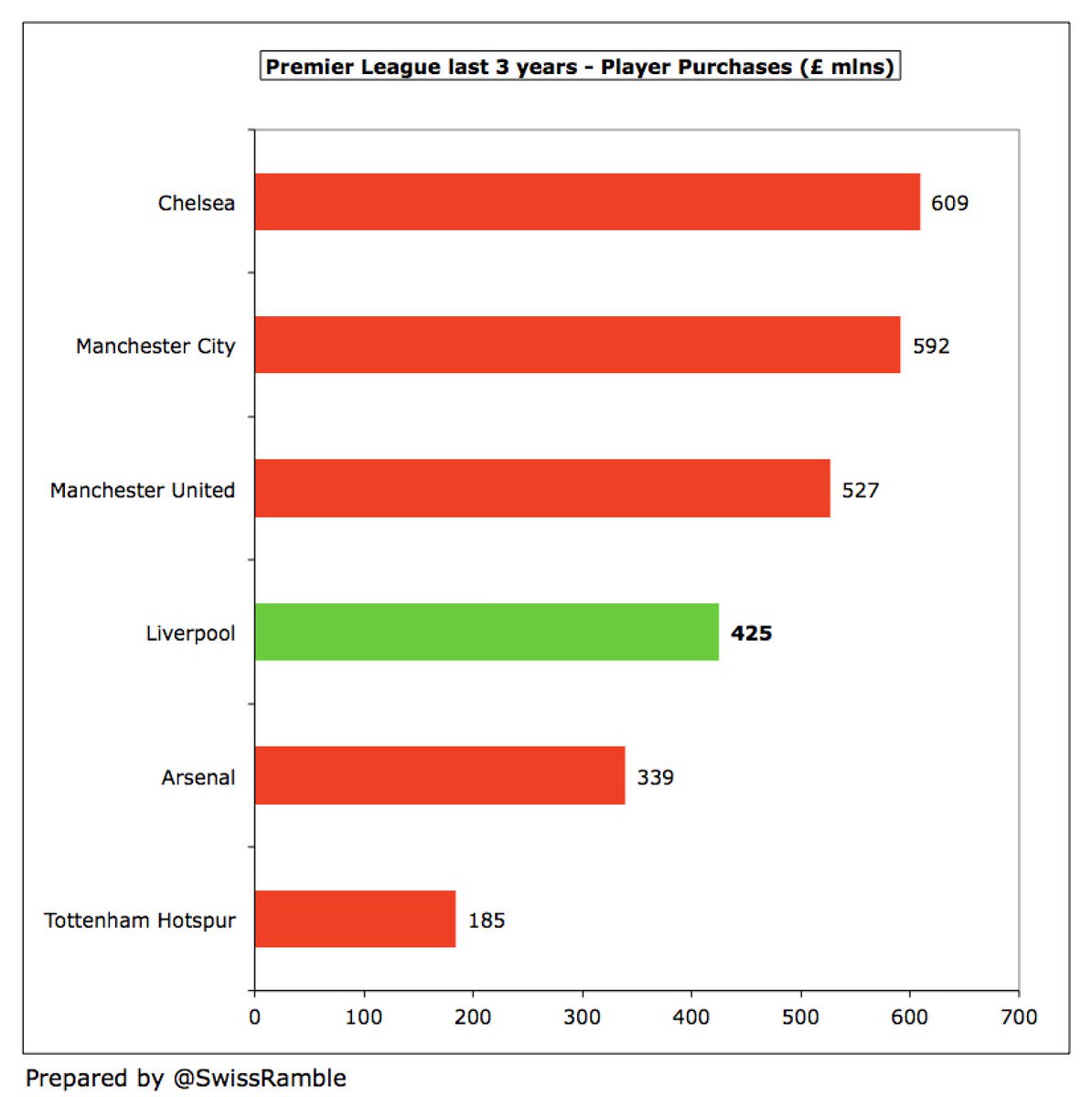

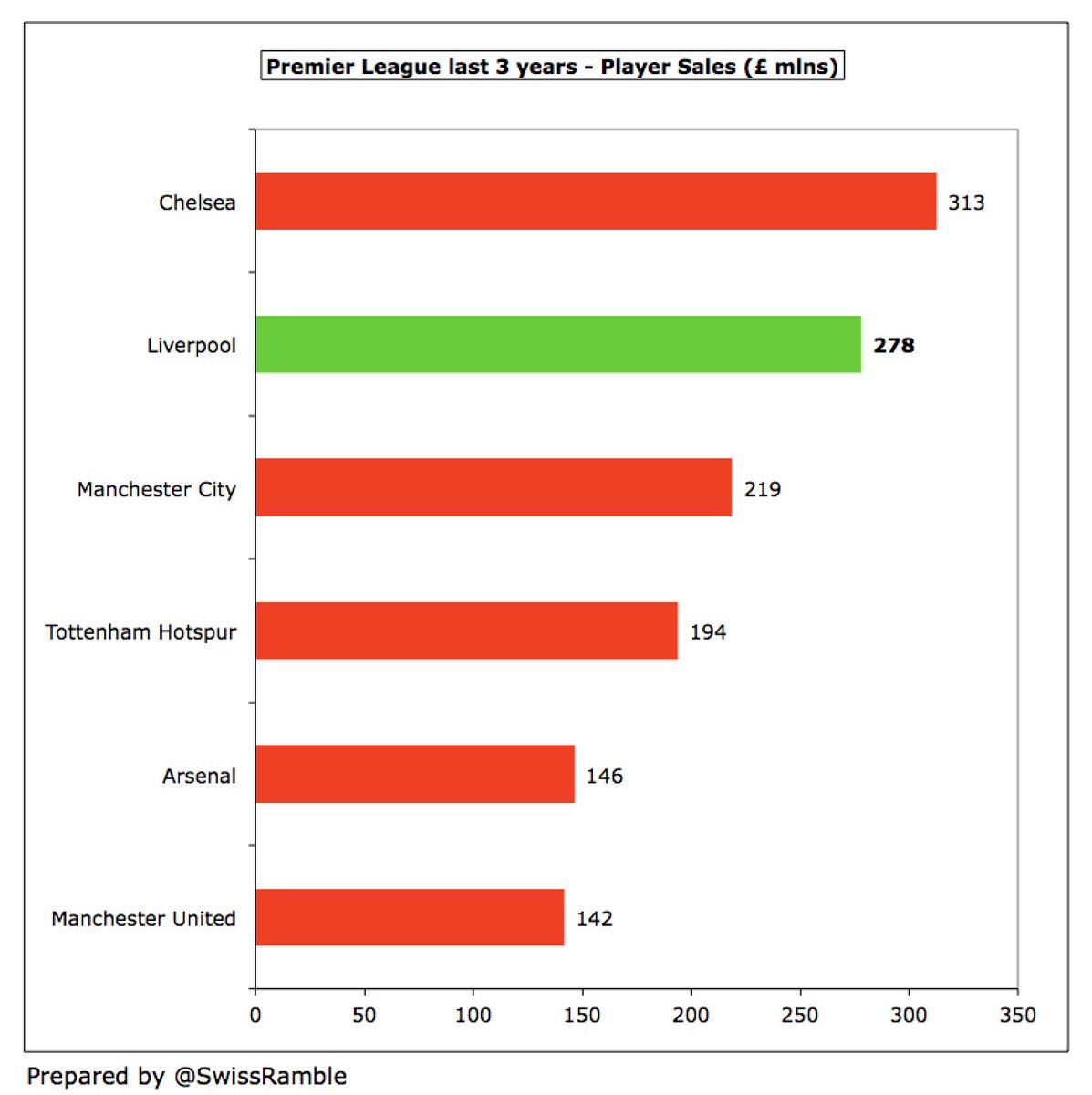

This helps explain why #LFC had much less money available to spend on players than their rivals, despite their reported high profits. As a consequence, they only spent £147m cash (net) in the last 3 years, the 2nd lowest in the Big 6, comprising £425m purchases less £278m sales.

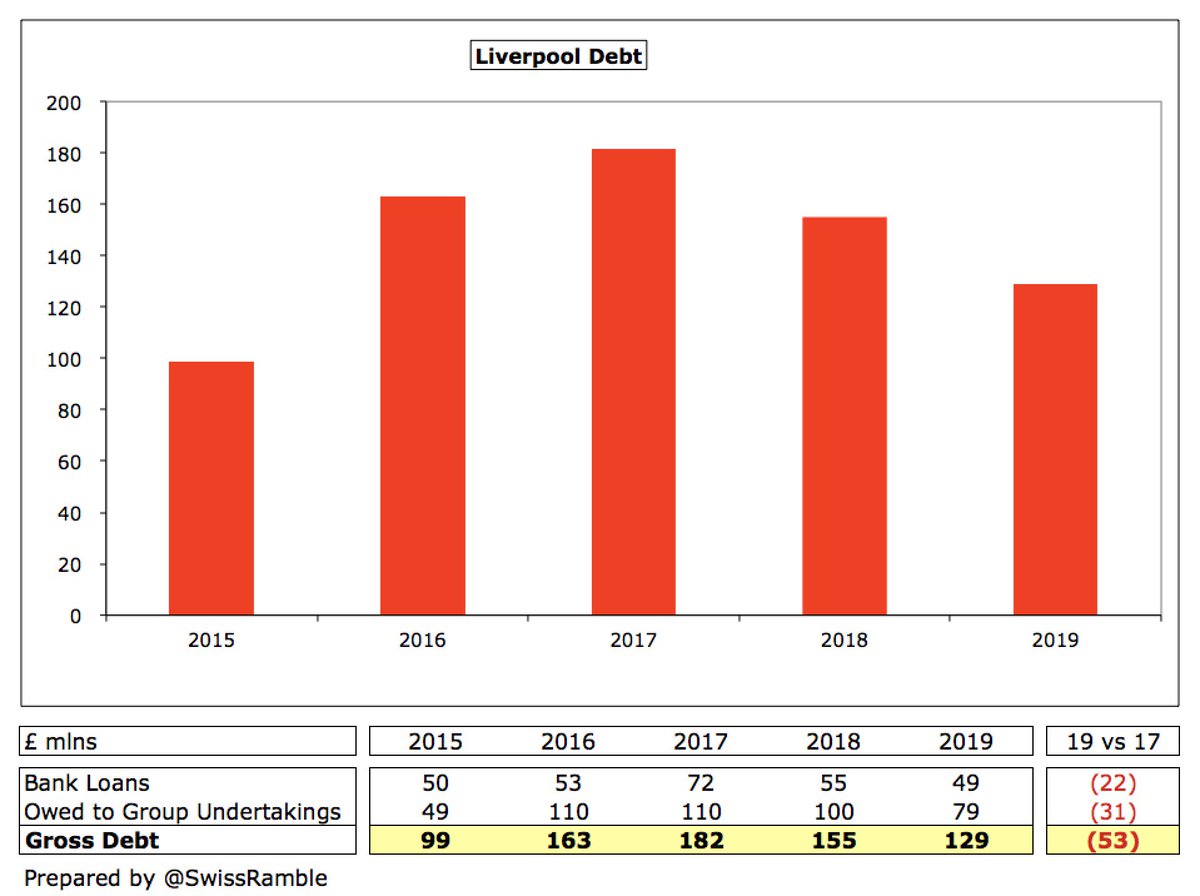

After the hideous Hicks and Gillett years, #LFC are now in a much better debt position. Indeed, they have actually managed to reduce debt by £53m in the last 3 years from £182m to £129m.

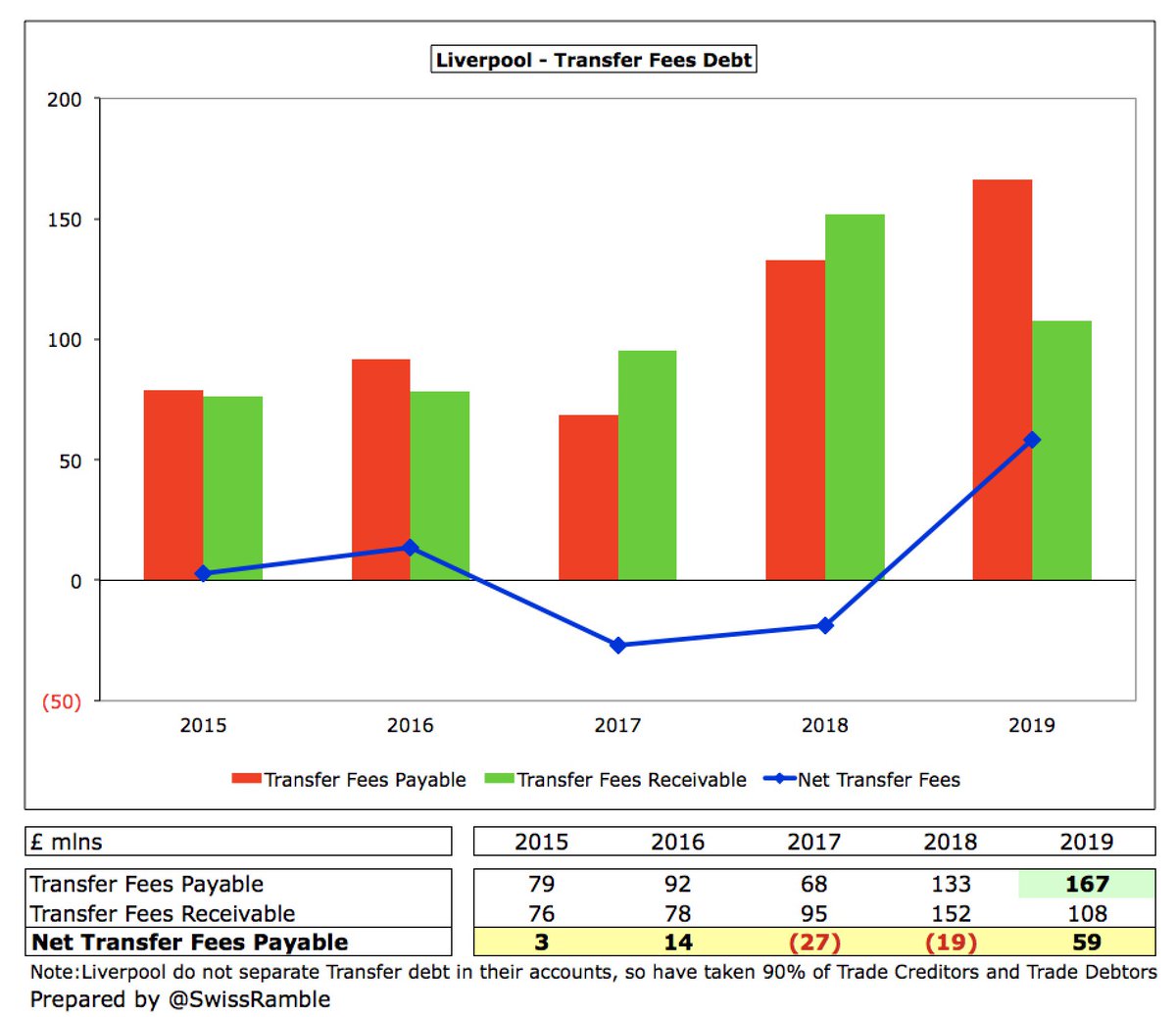

Furthermore, #LFC transfer debt, i.e. stage payments still owed for previous transfers, has been steadily increasing. This is not divulged in the accounts, but if we assume 90% of Trade Creditors, this was up to £167m in 2019 (£59m net of amounts owed by other clubs).

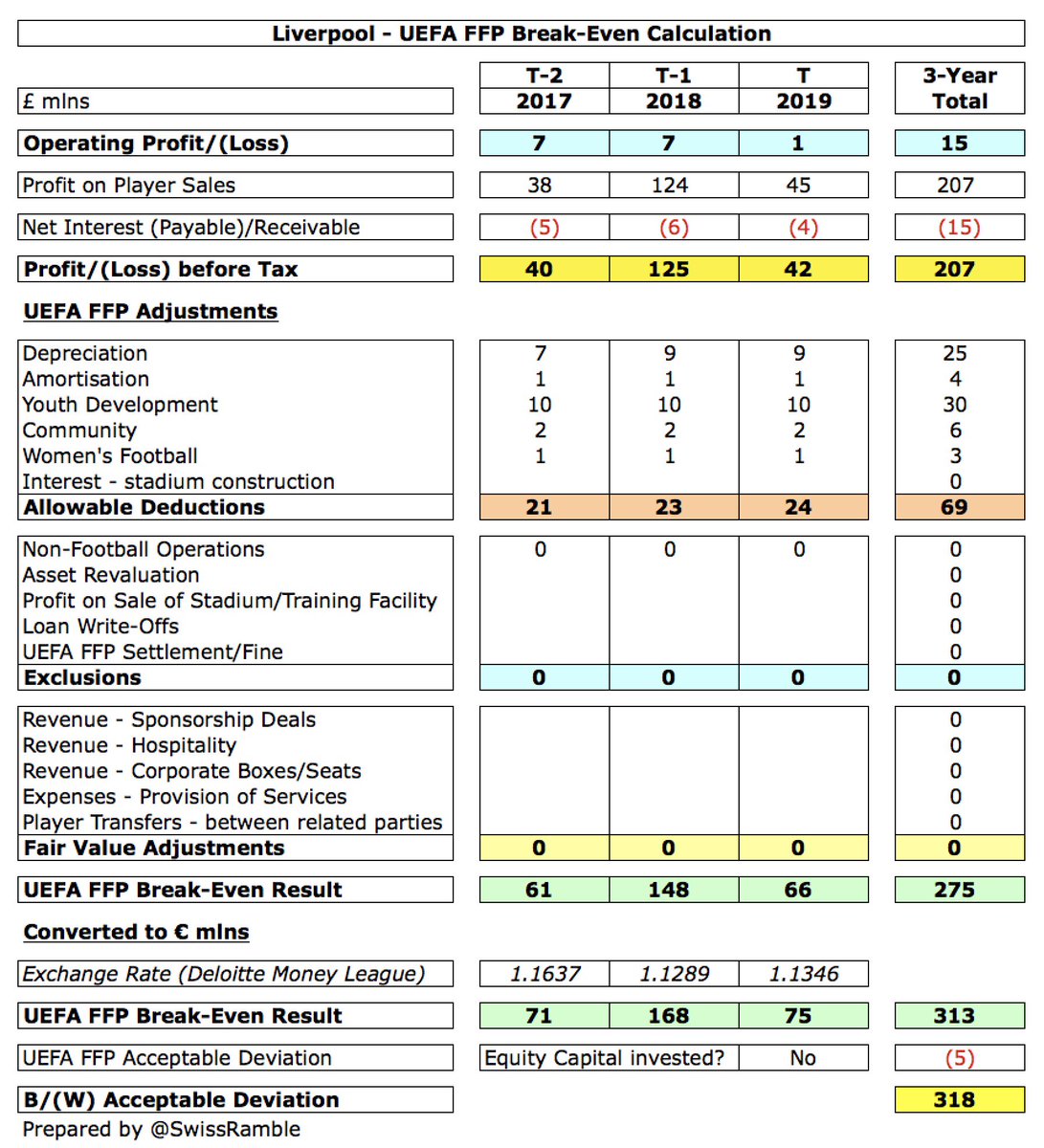

The good news is #LFC have absolutely no issues with Financial Fair Play. Their £207m profit over the three-year monitoring period is further boosted by £69m allowable expense deductions (youth, community, women, depreciation, etc), which gives them a £275m break-even surplus.

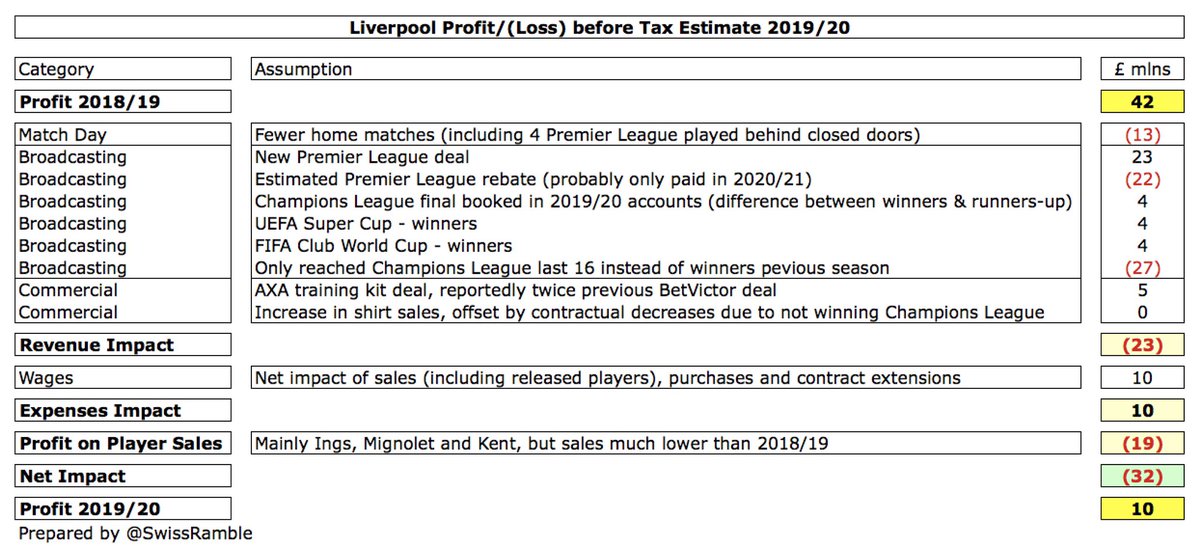

Looking ahead, I estimate that #LFC will report a worse financial result in 2019/20, albeit probably still a small pre-tax profit of £10m, compared to £42m in 2018/19. The assumptions include £23m lower revenue, £19m smaller profit on player sales, offset by £10m wages cut.

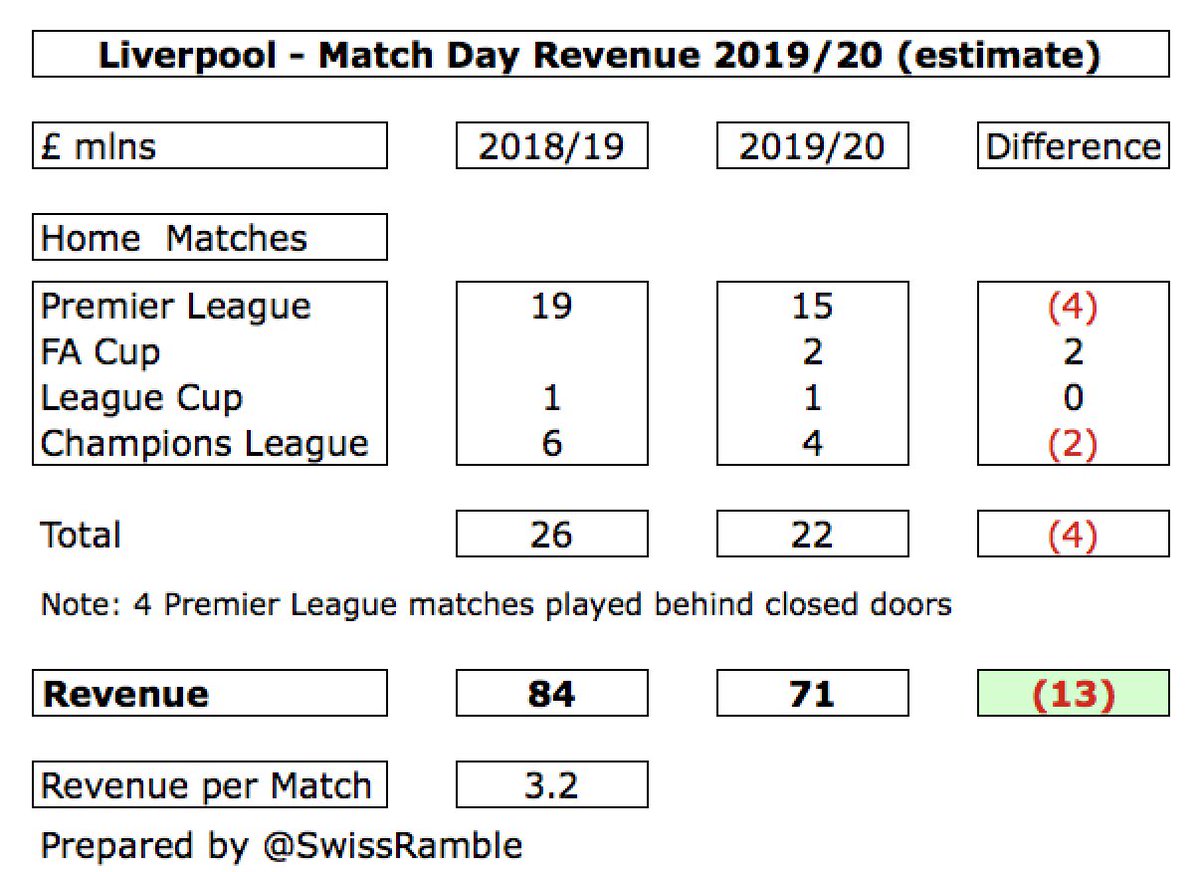

Based on average revenue of £3.2m a match, #LFC match day income will be around £13m lower in 2019/20, as there were 4 fewer matches, including 4 Premier League games played behind closed doors. The reduction in Champions League games was offset by more FA Cup games.

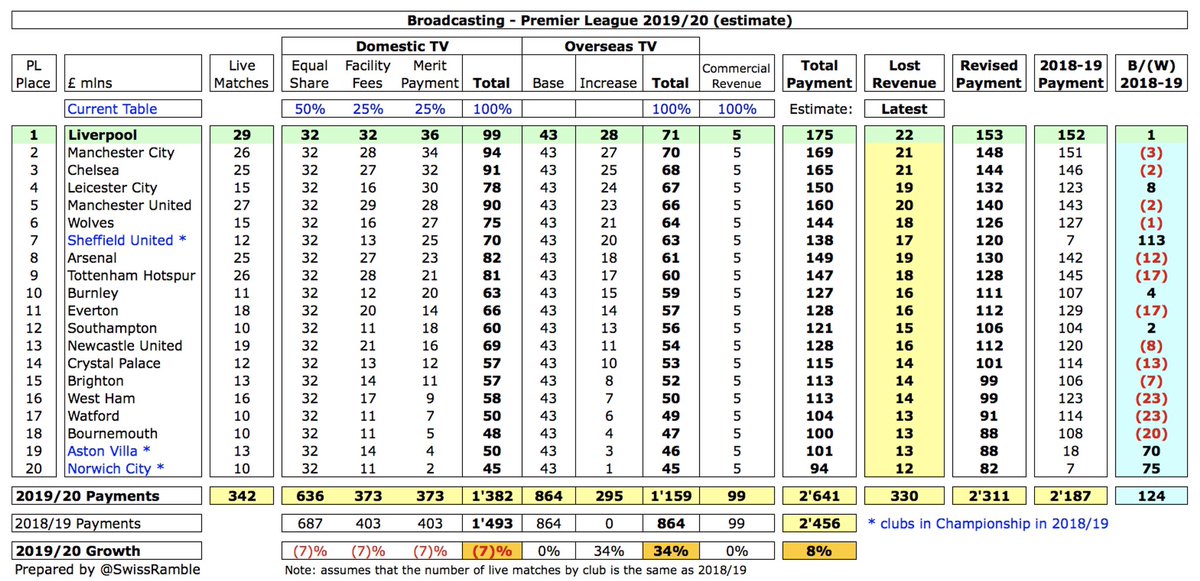

The new Premier League TV deal means #LFC distribution will increase by £23m from £152m to £175m, though this is almost entirely offset by their £22m share of the £330m rebate to TV companies. The Sky element will only be paid in 2020/21, but the overseas piece is this season.

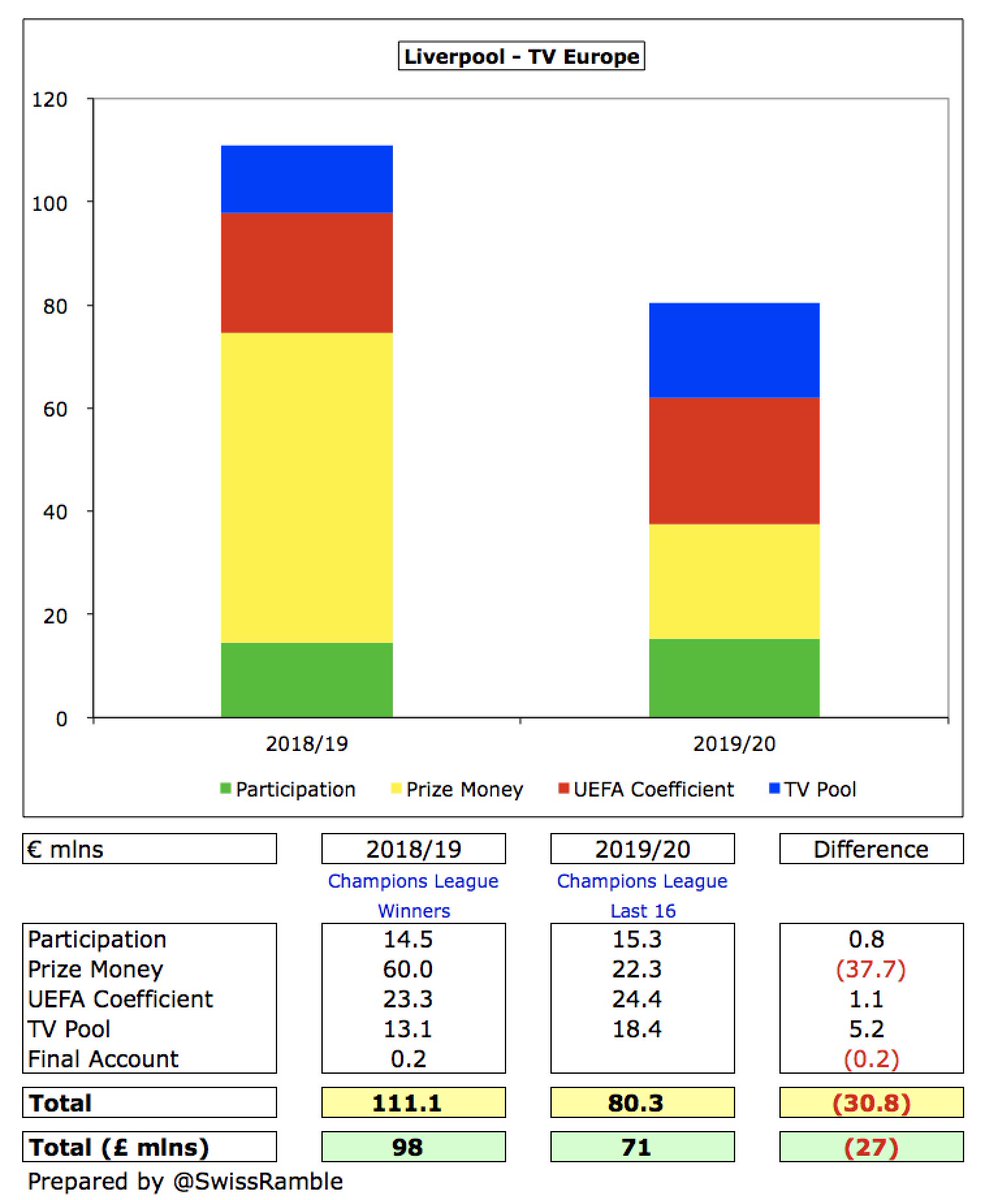

The impact of #LFC being eliminated in the Champions League last 16 by Atletico Madrid, compared to winning the trophy (for the 6th time) in 2018/19, is £27m (£71m vs. £98m). The decrease in prize money is slightly offset by a higher TV pool (better league position prior season).

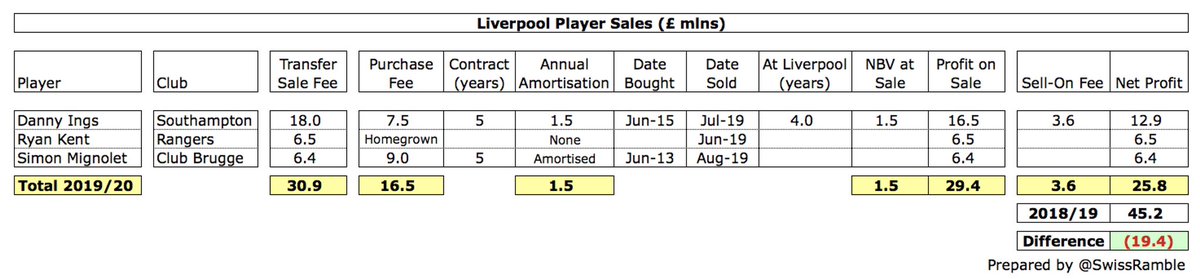

In addition, #LFC will report profit on player sales in 2019/20 of £26m (per my model), which is £19m lower than the £45m booked in 2018/19. This is mainly driven by sales of Danny Ings to Southampton, Ryan Kent to Rangers and Simon Mignolet to Club Brugge.

Like every other club, #LFC will be very concerned about the impact of COVID-19 on their finances. This is almost impossible to quantify, especially how this will affect sponsorships, including the lucrative new Nike kit deal, and when fans will be allowed back to the stadium.

To date, #LFC have not yet done this, though they have announced a delay to the Anfield Road Stand expansion, which could free up funds. They could also improve their cash position if they did not make £34m loan repayments (as they did in 2018/19)

Could #LFC invest more money in the transfer market? Yes, but they would probably have to “sell to buy”, unless they changed their business model, which would require increasing debt (either via an external loan or an injection from the owners).

جاري تحميل الاقتراحات...