WORK & LIVELIHOODS IN THE MAHJAR: today, I will share a few stories about the Syrian diaspora's labor economy, 1890s-1934.

We will talk about peddling, factory work, and the stories we (as historians) tell about them. I'll also touch on welfare/mutual aid.

au:@SDFahrenthold

We will talk about peddling, factory work, and the stories we (as historians) tell about them. I'll also touch on welfare/mutual aid.

au:@SDFahrenthold

First, some background reading, because the mahjar's labor economy was itself an extension of that of late 19th century Syria, Mt Lebanon, and Palestine.

The first migrants abroad were building on an economy focused on silk production in the Middle East: jstor.org

The first migrants abroad were building on an economy focused on silk production in the Middle East: jstor.org

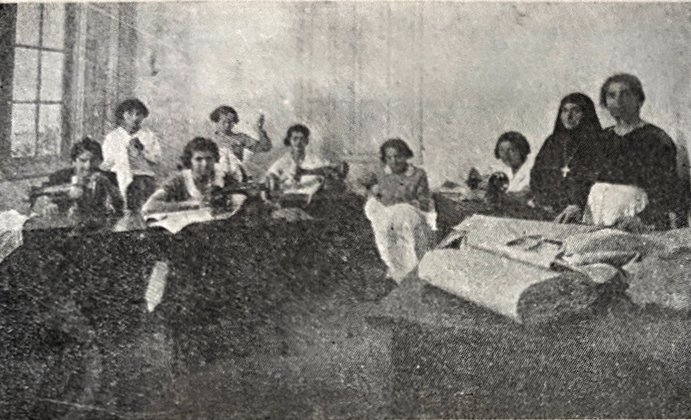

Second, Syrian women played primary roles in this migrant labor economy:

1. by working in silk factories to subsidize the emigration of male relatives,

2. by going abroad themselves to work as peddlers or in factories,

See: muse.jhu.edu

1. by working in silk factories to subsidize the emigration of male relatives,

2. by going abroad themselves to work as peddlers or in factories,

See: muse.jhu.edu

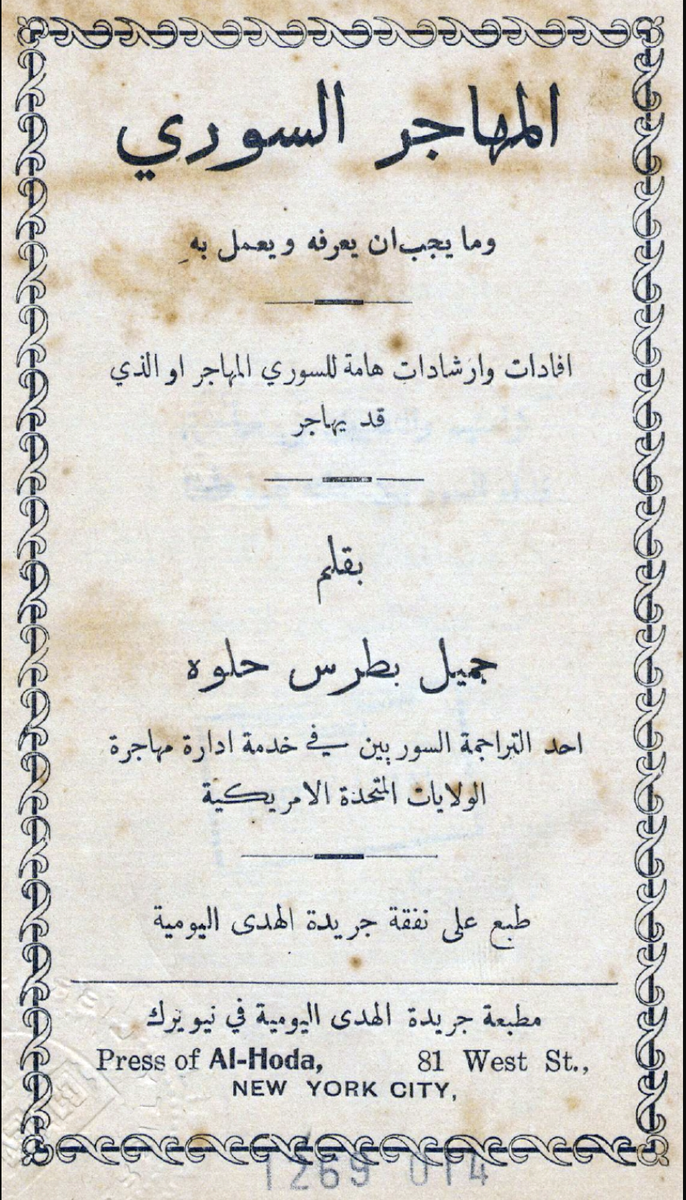

The booklet describes the immigration process, and what questions Syrians could expect. It's also a constitutional primer, arming these immigrants with the knowledge to protect themselves.

Read it here: iiif.lib.harvard.edu

Read about it here: migrantknowledge.org

Read it here: iiif.lib.harvard.edu

Read about it here: migrantknowledge.org

Anyway, in the very beginning of the Syrian migration to the Americas, most of those who went abroad were men. (Women later formed 35% of this diaspora, around 1900).

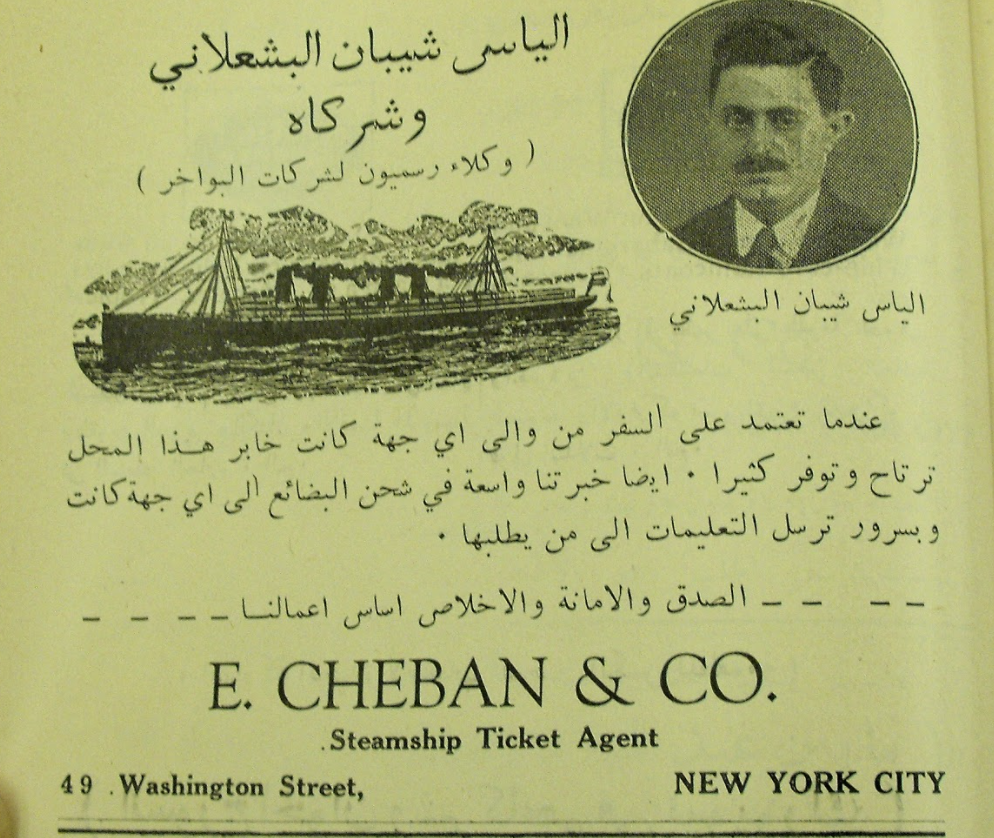

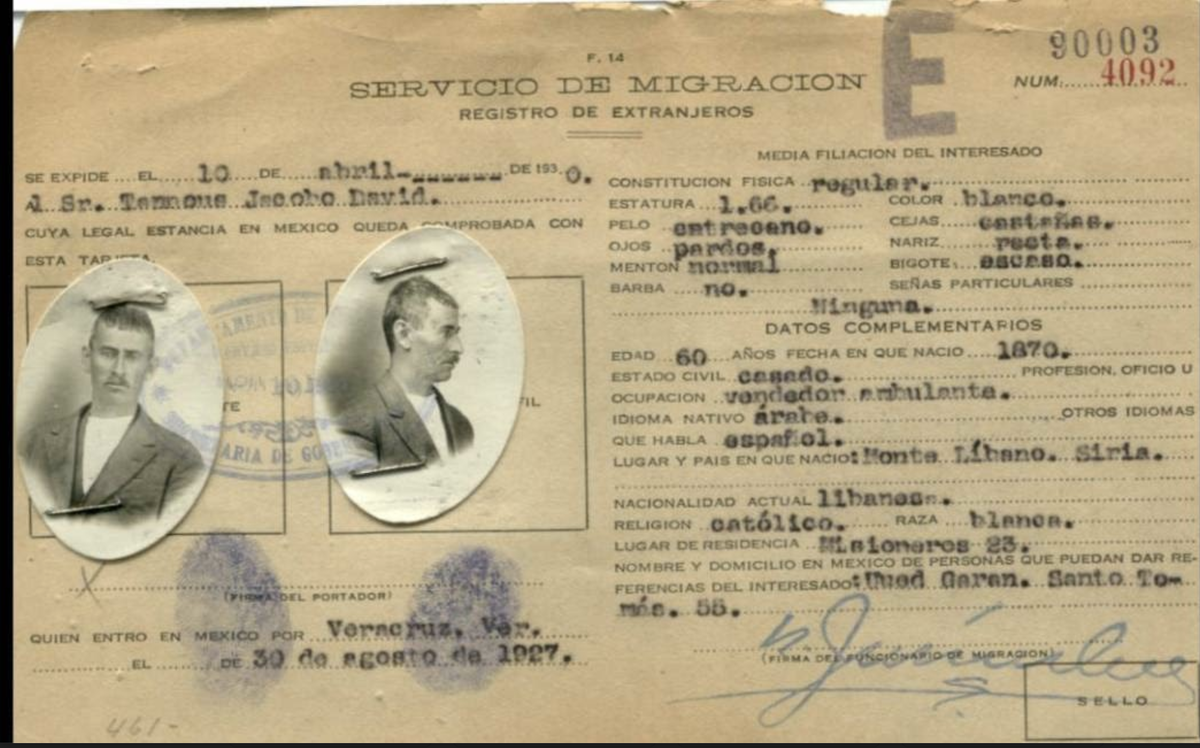

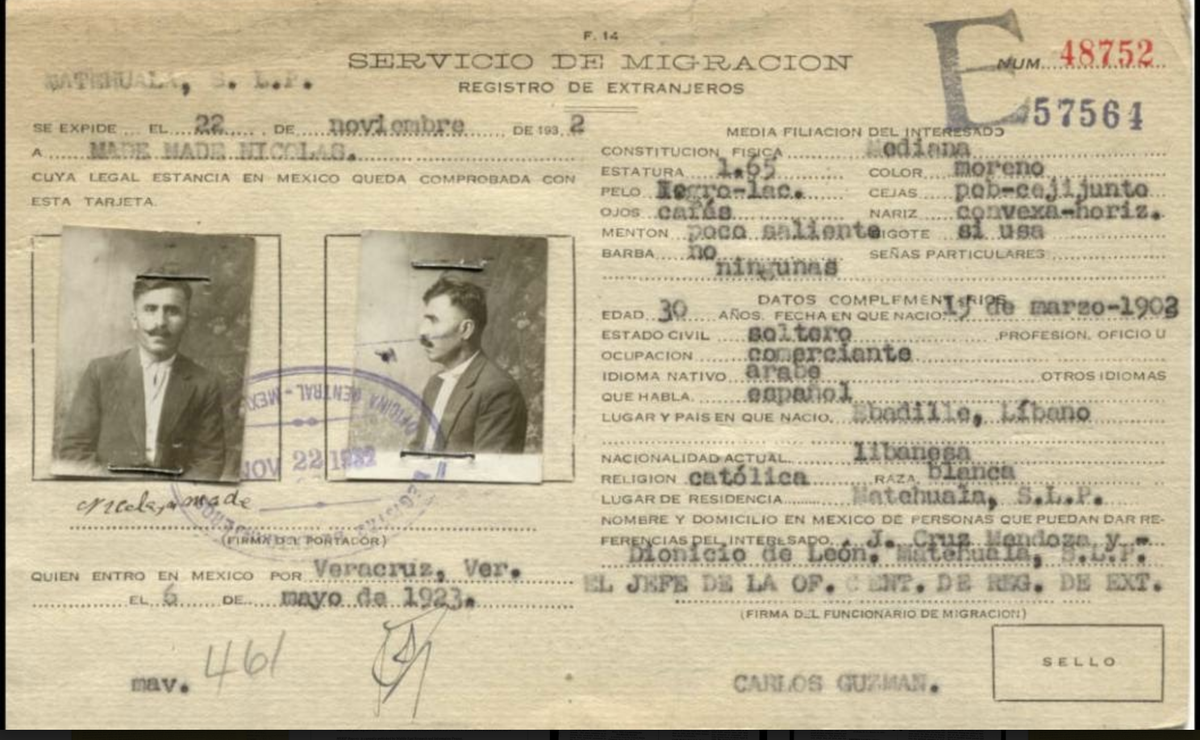

Arriving in the port, most connected directly to Syrian employment agents who helped set them up with work.

Arriving in the port, most connected directly to Syrian employment agents who helped set them up with work.

Itinerant commerce was well-suited for newly arriving Syrians, especially the "family firsts" who lacked start-up capital, local languages/cultures.

By 1900, Syrian importers in larger colonies like New York, Bueno Aires, Sao Paulo granted peddlers loans/items on consignment.

By 1900, Syrian importers in larger colonies like New York, Bueno Aires, Sao Paulo granted peddlers loans/items on consignment.

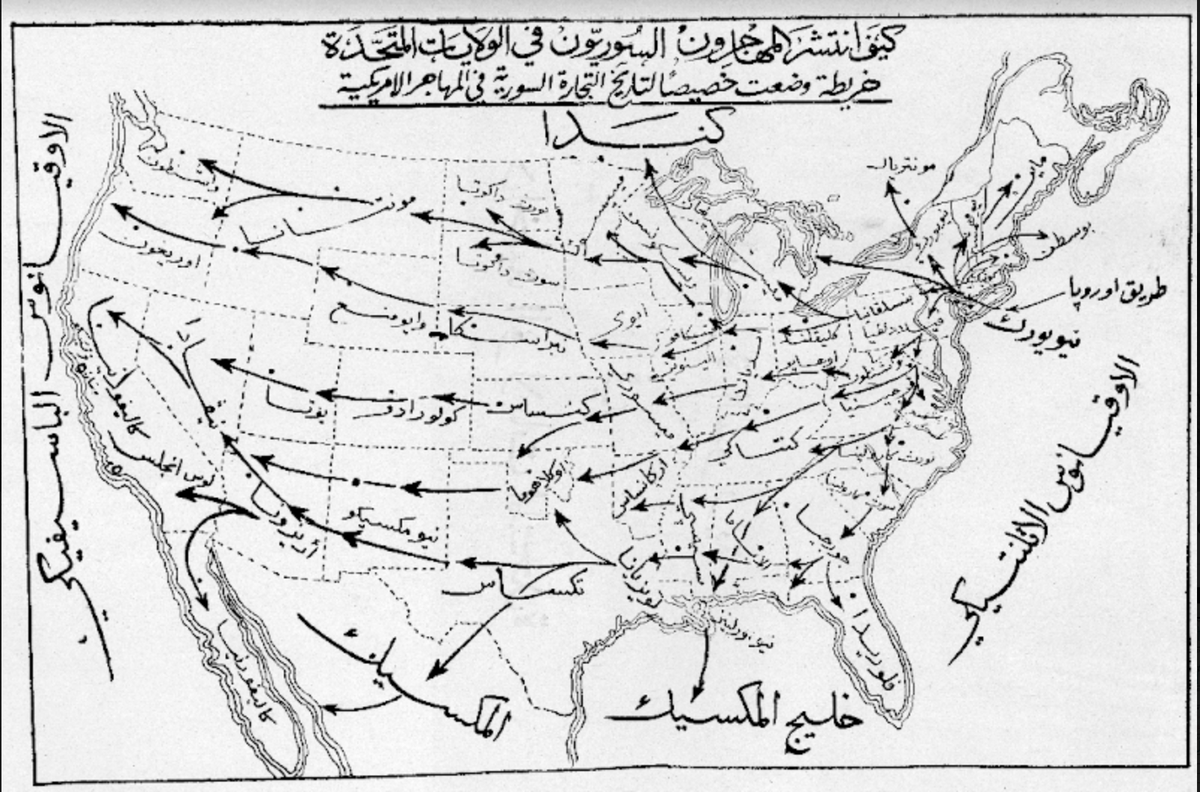

...or by carrying goods or managing small-time commerce in small towns/rural spaces beyond the cities, as illustrates by this map of "peddling routes" printed in Syrian New York:

and in the case of Argentina, in @DrPearlBallo's new book: sup.org

and in the case of Argentina, in @DrPearlBallo's new book: sup.org

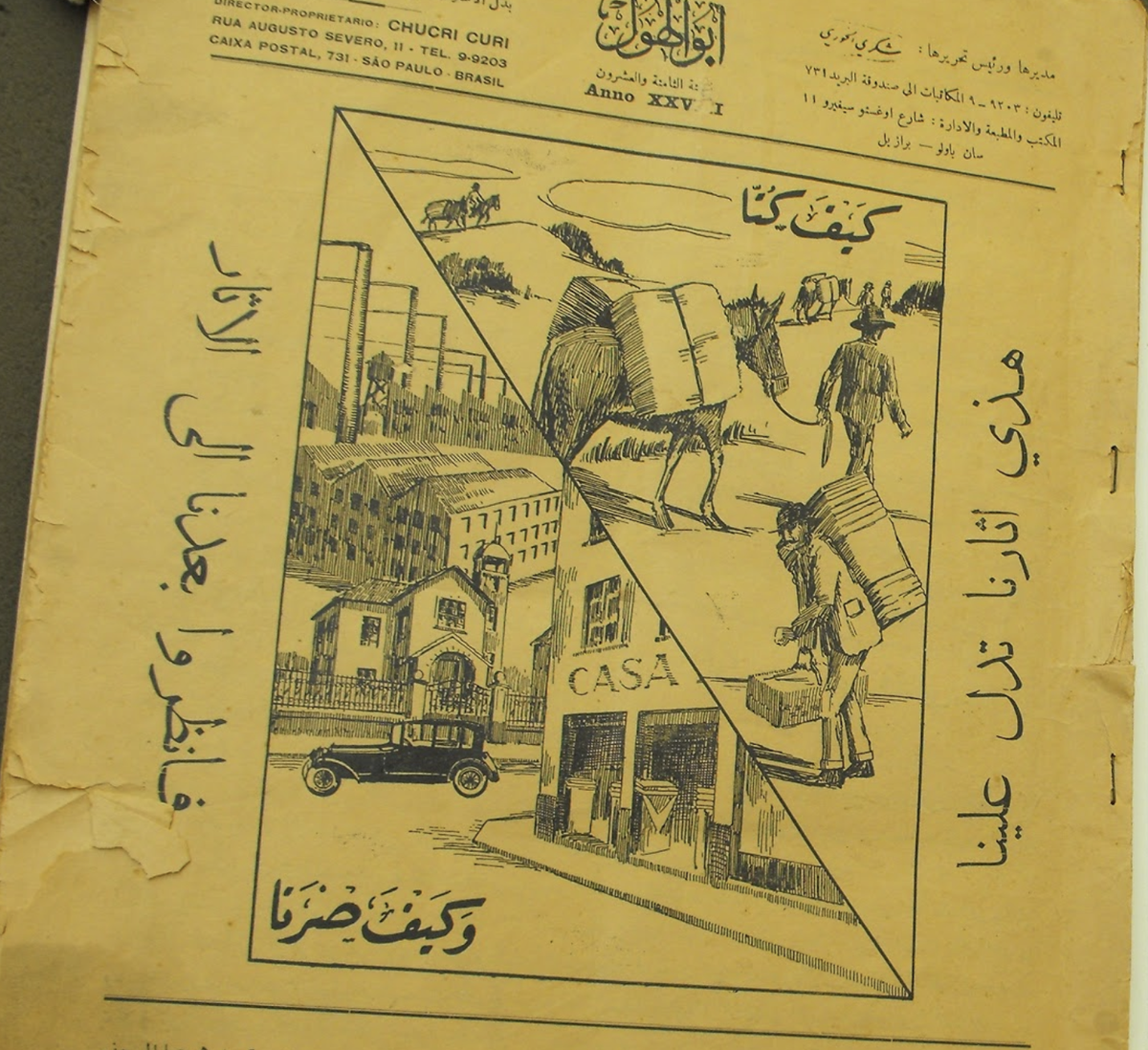

Now, one thing I think is interesting about mahjari archives is this fixation on the pack peddler.

Peddling comprised one important economic activity in this diaspora. But:

1. peddling was one facet of a larger labor economy.

2. other industries are unremarked in the sources.

Peddling comprised one important economic activity in this diaspora. But:

1. peddling was one facet of a larger labor economy.

2. other industries are unremarked in the sources.

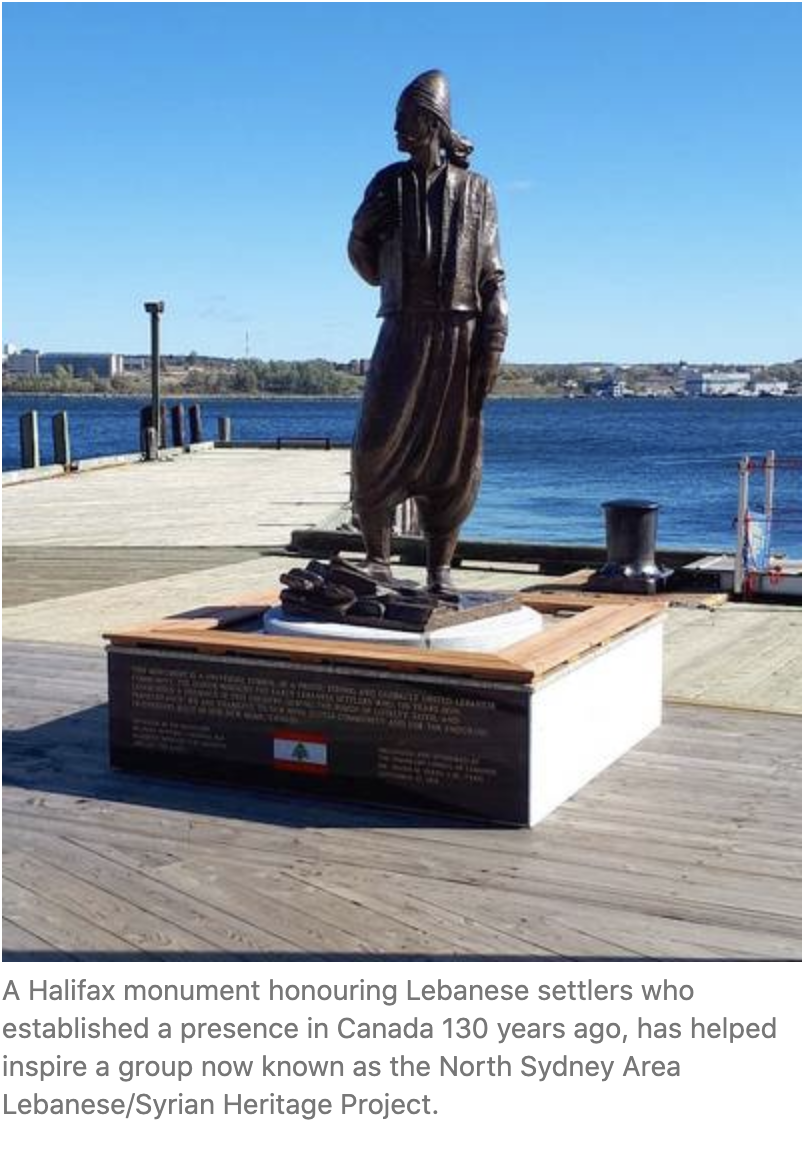

Peddlers have been literally monumentalized around the diaspora, where they are triumphalist totems of economic success.

These statues in Halifax, Canada and Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

John Tofik Karam wrote about this memorialism here: lebanesestudies.news.chass.ncsu.edu

These statues in Halifax, Canada and Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

John Tofik Karam wrote about this memorialism here: lebanesestudies.news.chass.ncsu.edu

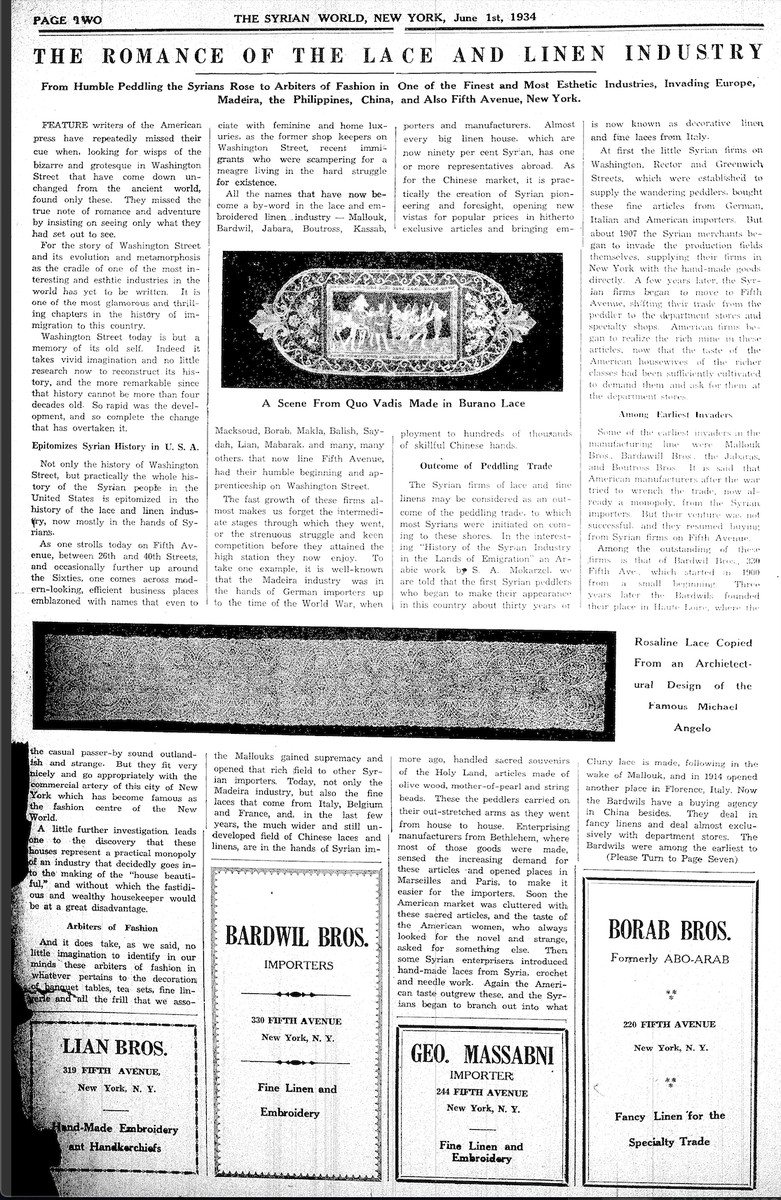

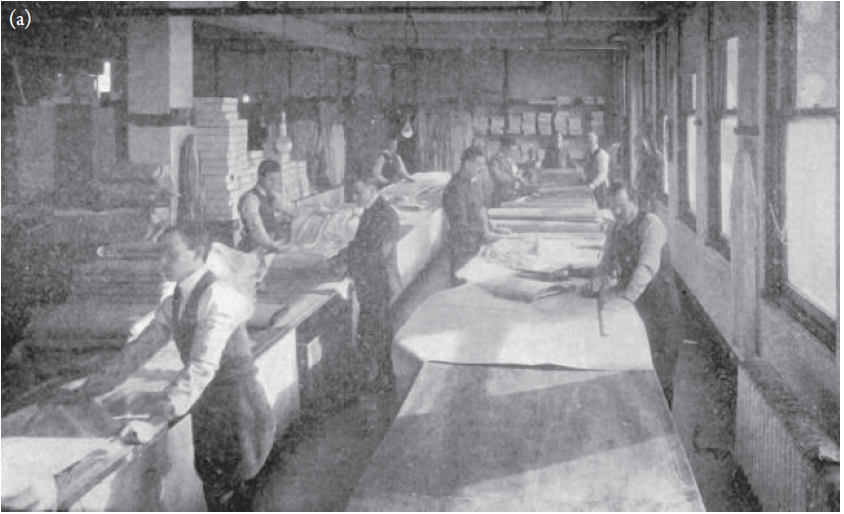

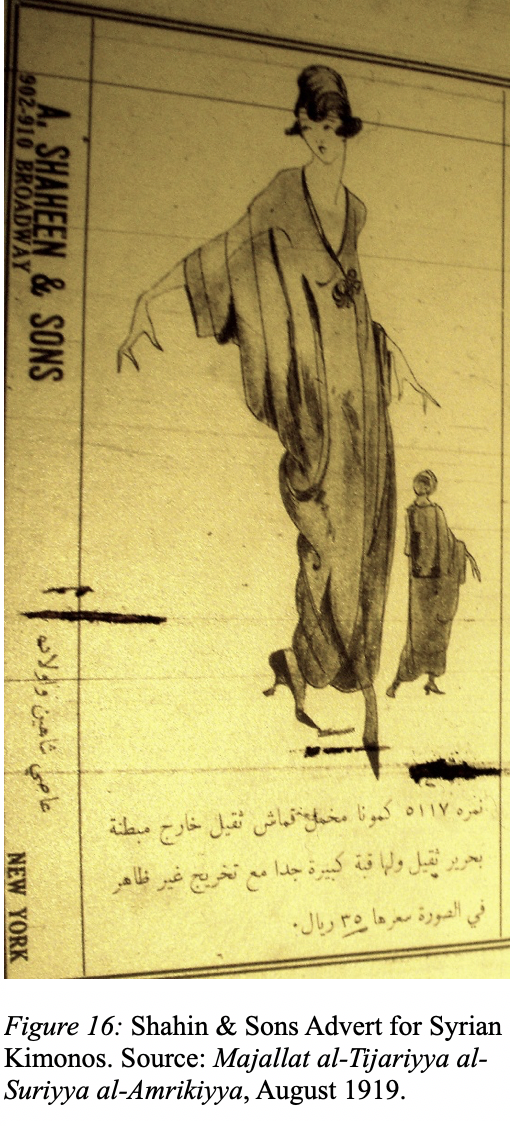

Both Syrian men & women engaged in all facets of textile work. However, this industry also trended in strictly gendered ways, too.

Syrian women were more likely doing in-home garment work (as seamstresses and laces).

Men were more likely to go into importing/wholesaling.

Syrian women were more likely doing in-home garment work (as seamstresses and laces).

Men were more likely to go into importing/wholesaling.

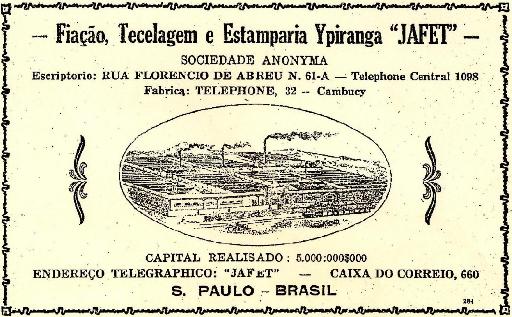

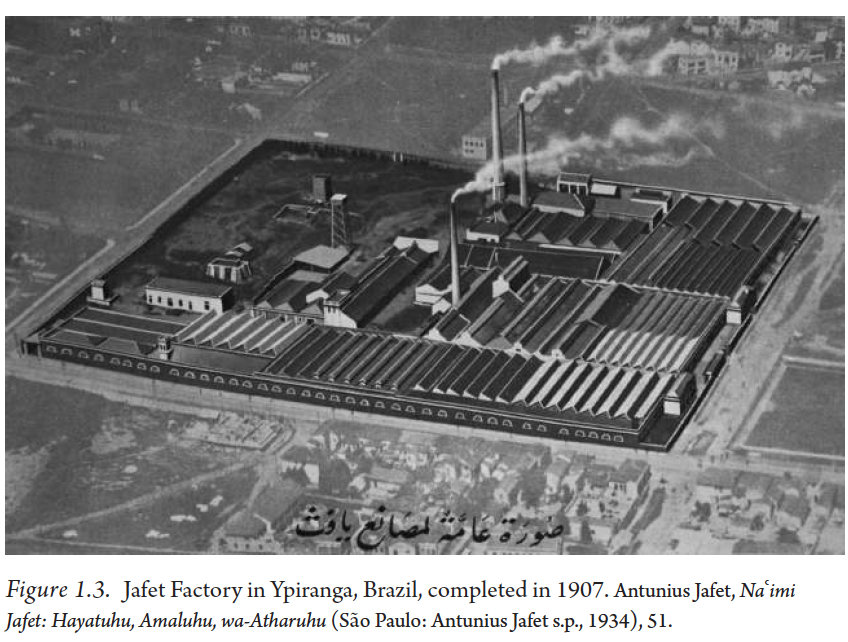

In New York City's "little Syria" neighborhood, dozens of Syrian-owned factories competed for a share of the silk, shirtwaist, and apron markets by 1910.

Syrian workers also labored in factories owned by Americans, but tended to favor jobs under Syrian immigrant proprietorship.

Syrian workers also labored in factories owned by Americans, but tended to favor jobs under Syrian immigrant proprietorship.

The family economy of Syrian households was also shaped by this system of complementarity in production.

Often, Syrian women were the wage-earners of their families. Their wages in textile work paid bills, and subsidized the riskier commercial ventures of male relatives.

Often, Syrian women were the wage-earners of their families. Their wages in textile work paid bills, and subsidized the riskier commercial ventures of male relatives.

In New York/New England, Syrian women also engaged in worker welfare organizations and mutual aid organizations centered on the provision of unemployment insurance, emergency relief, and even boarding houses for Arab workers unable to work/injured by the looms.

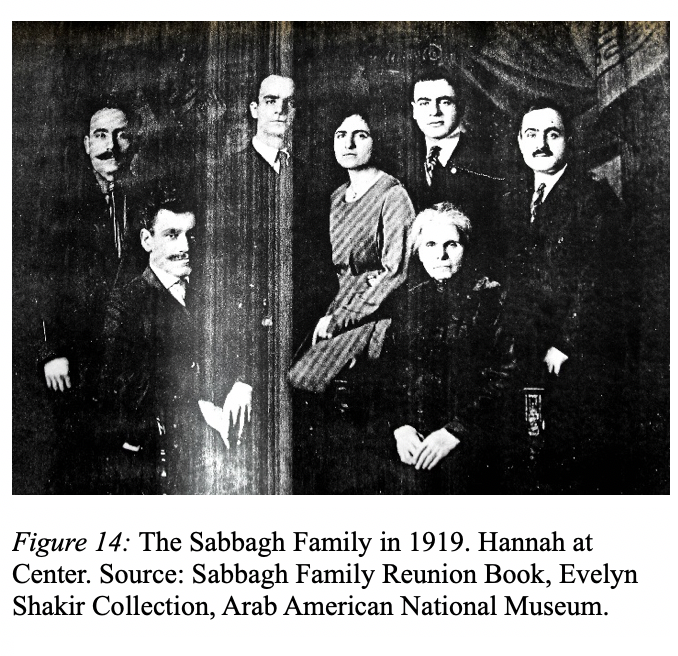

In 1917, Boston got its own Syrian Ladies Aid Society, under the leadership of (above mentioned) Hannah Sabbagh. The SLAS of Boston offered assistance and relief to Syrians across the New England region, connecting women with job training, etc.

These charitable networks helped the mahjar weather the Great Depression and propelled many into prosperity after World War II.

Hannah Sabbagh Shakir (married in 1931) came out of the 1940s with a small skirt factory. The @ArabAmericanMus has a couple!

arabamerican.pastperfectonline.com

Hannah Sabbagh Shakir (married in 1931) came out of the 1940s with a small skirt factory. The @ArabAmericanMus has a couple!

arabamerican.pastperfectonline.com

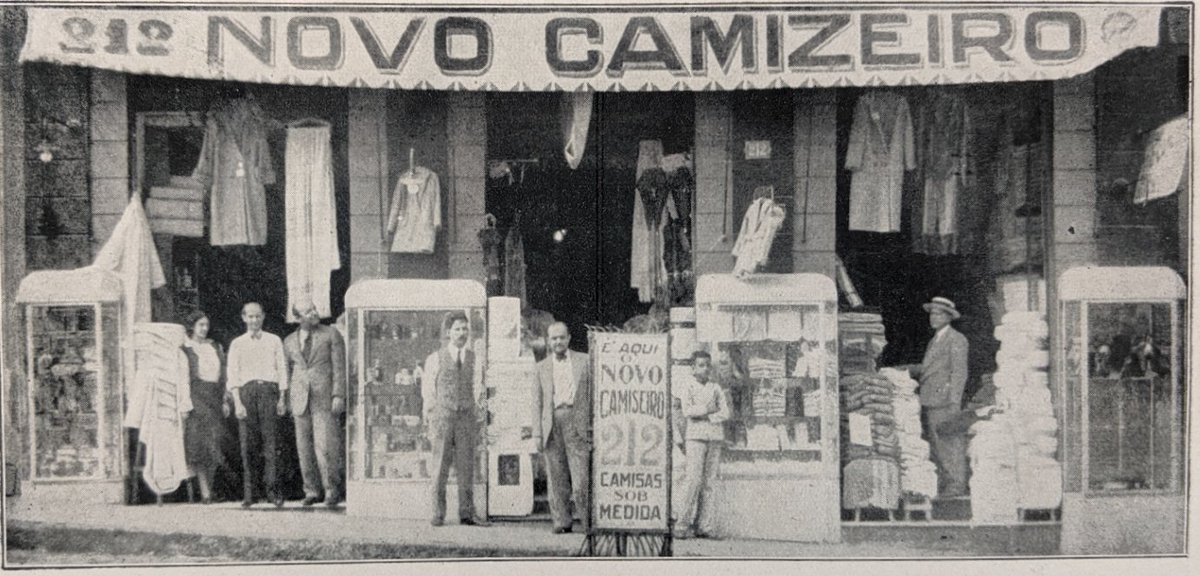

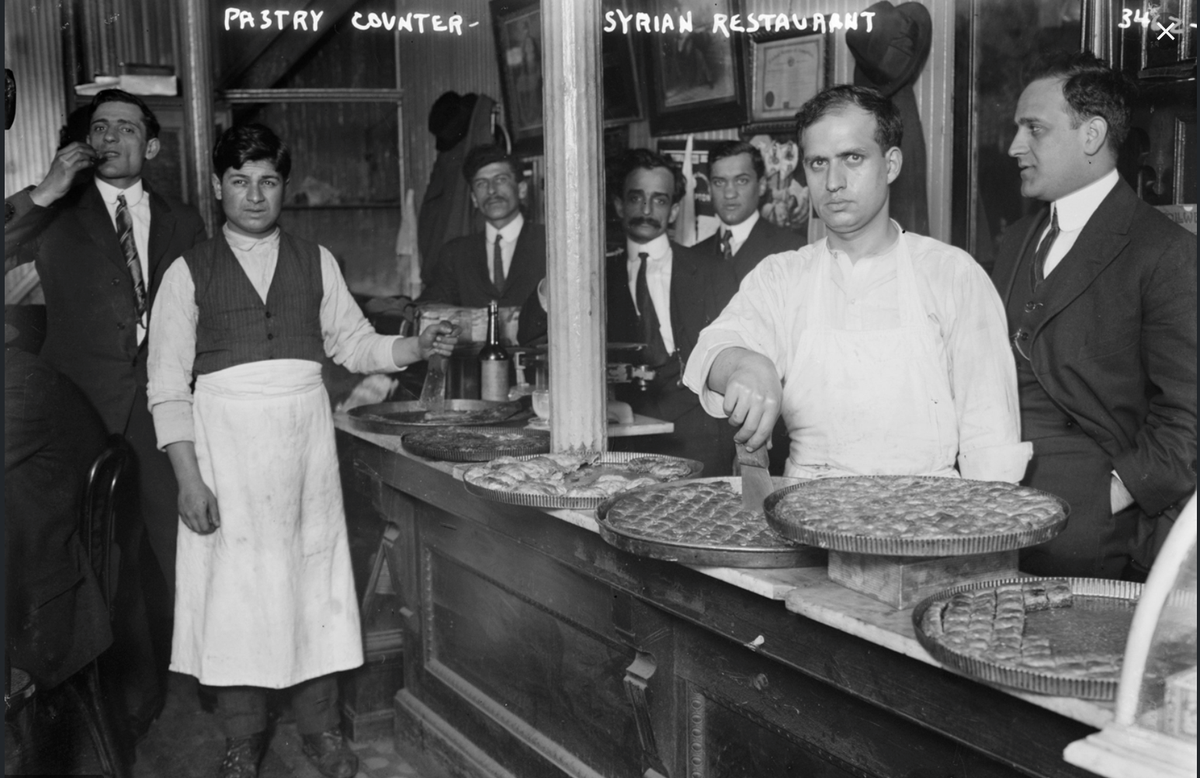

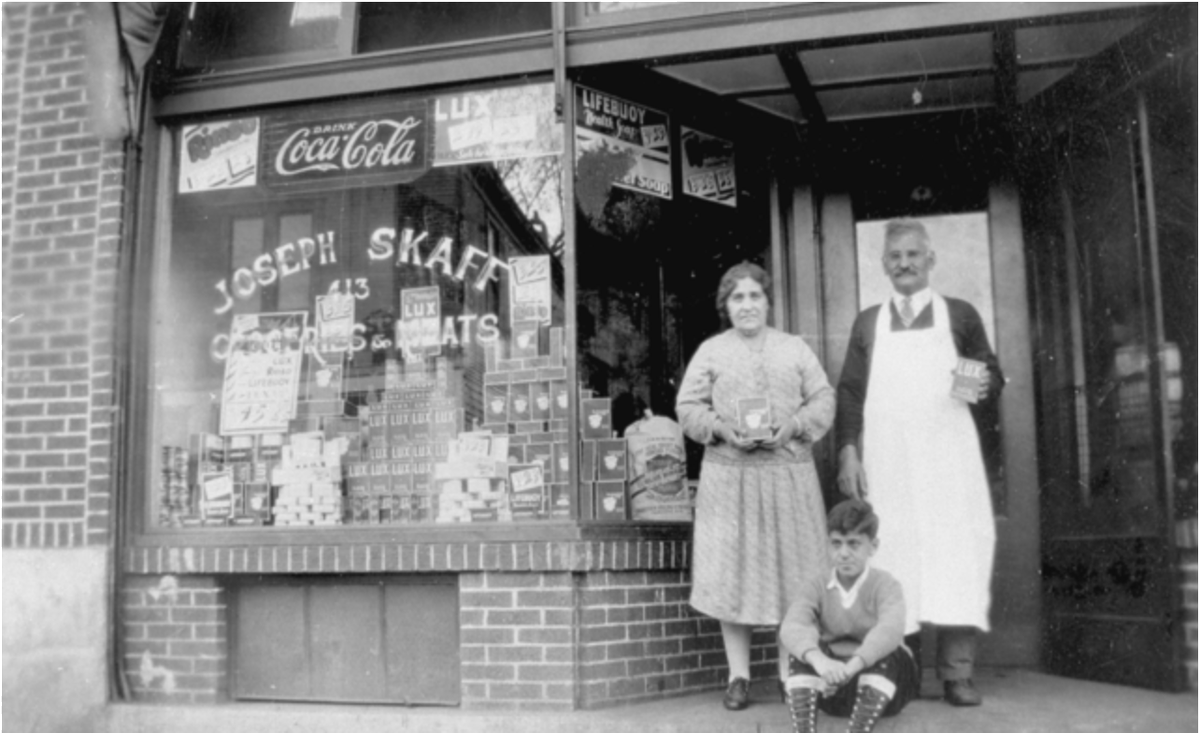

Beyond peddling and textile production, Syrians in the mahjar worked in many sectors. They were haberdashers, winemakers, owners of cafes/restaurants.

Some of the most famous images of NYC's little Syria are from @librarycongress and show a cafe:

Some of the most famous images of NYC's little Syria are from @librarycongress and show a cafe:

Agricultural labor was rarer among Syrians in the USA, but this work was still available.

Here are Syrian children working in a cranberry bog in Massachusetts, 1911.

Source: @librarycongress loc.gov

Here are Syrian children working in a cranberry bog in Massachusetts, 1911.

Source: @librarycongress loc.gov

This thread comes to a less firm conclusion, bc I'm writing about Syrian workers right now. But the point: the same sources we've used to tell mahjar stories "beyond the state" are also class-specific. Workers claim less space in them owing to the politics of their production.

In my final thread on @Tweetistorian, I will explore where we go from here in THE MAHJAR ONLINE.

How will #twitterstorians of the Syrian mahjar do research in this time of #Covid_19? Thankfully, though a series of digital collections that make new research possible.

Join me!

How will #twitterstorians of the Syrian mahjar do research in this time of #Covid_19? Thankfully, though a series of digital collections that make new research possible.

Join me!

جاري تحميل الاقتراحات...