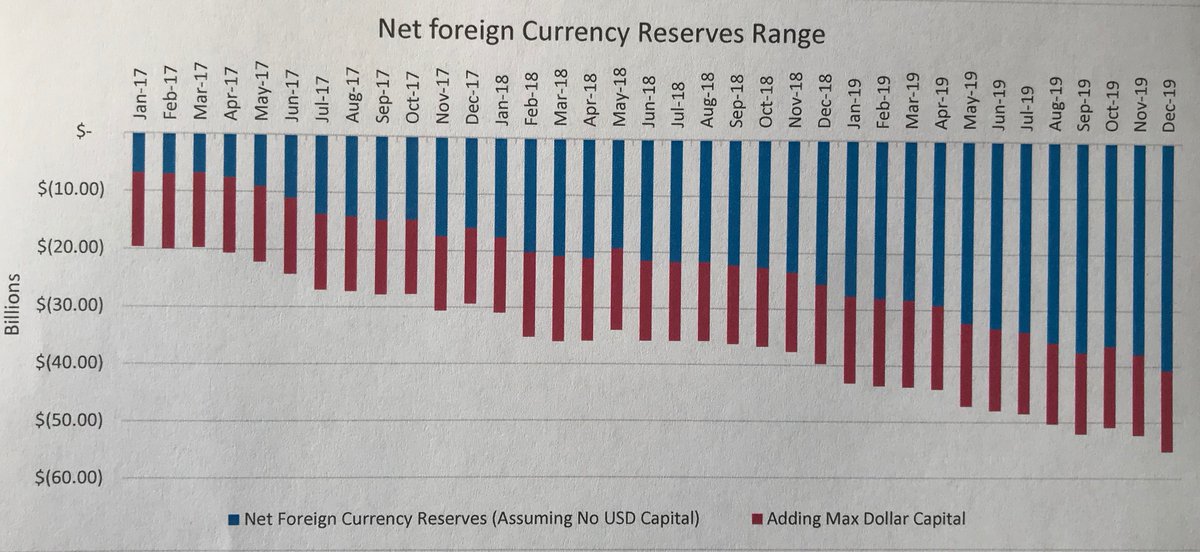

3. Under the first method, Net FX Reserves were around -$40bn (banks' $ deposits = $70bn) in Dec-19, the famous number circulating the media.

While second reflects Net FX Reserves of ~ -$57bn, as banks' $ deposits are estimated at $87bn.

So which number is it?

While second reflects Net FX Reserves of ~ -$57bn, as banks' $ deposits are estimated at $87bn.

So which number is it?

5. Why do net reserves have any meaning?

Because one way a CB accumulates gross reserves (the supposed $30bn) is by borrowing from banks. If Bank A deposits $100 at the CB, the CB now has $100 as a foreign asset, it deposits the borrowed fresh $ in a current account abroad.

Because one way a CB accumulates gross reserves (the supposed $30bn) is by borrowing from banks. If Bank A deposits $100 at the CB, the CB now has $100 as a foreign asset, it deposits the borrowed fresh $ in a current account abroad.

6. On the other side, it now also owes $100 to Bank A. So Net FX Reserves are zero while the Gross are $100.

Now imagine a $50 bottle of whiskey, crafted by Baal's French mistress, catches Mr Phoenicia's eye. He rushes to buy it, grasping onto his last LBP75,000.

Now imagine a $50 bottle of whiskey, crafted by Baal's French mistress, catches Mr Phoenicia's eye. He rushes to buy it, grasping onto his last LBP75,000.

7. He arrives at Bank A, out of breath, hands his liras to his favorite teller begging him to transfer them to Baal's mistress in Bank B. Unfortunately, the mistress and Bank B won't accept the liras.

The teller tells him about Bank A's kindest service: exchanging his liras for $

The teller tells him about Bank A's kindest service: exchanging his liras for $

8. Mr Phoenicia quickly accepts the offer, thanking Bank A and the stability of the lira, and asks to transfer $50 to France (cause **** the euro).

What the hell does Bank A with LBP and how does it get the $50 back that actually belong to Mr Phoenicia's responsible sister?

What the hell does Bank A with LBP and how does it get the $50 back that actually belong to Mr Phoenicia's responsible sister?

9. They run to their favorite CB that promised Bank A it would always buy its liras in exchange for $ at a fixed rate. The CB dips into its gross reserves, credits Bank As account $50 & reduces the Lira account by LBP75,000

Bank A then transfers the $50 to France, through the CB

Bank A then transfers the $50 to France, through the CB

10. What happens now? The Central Bank Currently has $50 in its current account abroad, while it still owes $100 to Bank A.

Now imagine Mr Phoenicia's responsible sister decides to transfer $50 from her account to her son studying in Sorbonne.

Now imagine Mr Phoenicia's responsible sister decides to transfer $50 from her account to her son studying in Sorbonne.

11. Bank A asks the CB to transfer $50 from its account to France (the kid likes dollars too). The CB dips into its gross fx reserves again and transfer $50 to the kid's bank account.

No problem, it's not like there's nothing left as long as Bank A keeps its other $50.

No problem, it's not like there's nothing left as long as Bank A keeps its other $50.

12. Then Mr Badde Mosriyyete asks to transfer $50 from his account at Bank A to his account in Cyprus, where he likes to spend his lira salary, after exchanging them for dollars, every two weeks.

Bank A rushes back to the CB asking for the transfer, the CB flips it off.

Bank A rushes back to the CB asking for the transfer, the CB flips it off.

13. Mr Badde Mosriyyete rages at Bank A demanding to transfer his money, Bank A flips him off. Then Mr Bade Mosriyyete and his cousins rush the streets asking for their money, Bank A and its colleagues flip them off.

14. All they have is hope they'd accept those useless liras instead, at the same rate they could buy the dollar in the good old yesterday.

That's negative net reserves. The only way for them to turn positive again is if its FX debt disappears or if it's exchanged for liras.

That's negative net reserves. The only way for them to turn positive again is if its FX debt disappears or if it's exchanged for liras.

15. The above are only simple ways of how it depletes.

It also happens when bank A decides to lend people with lira income in USD, feeding the cycle of USD fractional reserve banking and expansion of private dollar debt.

It also happens when bank A decides to lend people with lira income in USD, feeding the cycle of USD fractional reserve banking and expansion of private dollar debt.

16. It also happens when most of those borrowed dollars are not invested in a project with positive fresh dollar cash flows, driving debtors to settle their $ debt using lira income.

17. It also happens when the government borrows in USD, disillusioned with its past cheap cost, and asks the central bank to make payments on its behalf in exchange for the liras it initially borrowed from the central bank itself.

18. It also happens when people exchange their lira savings for USD savings, in a country with no dollar returns, for lower (but high) interest rates thinking the risk of the lira is worth the price of the their new dollars' safety .

19. It also happens when the $ gets scarce and the thirst for it increases, driving its price (interest rate), Mr Bade Mosriyyete's dollar account, and banks' and the central bank's cost to borrow it up.

20. It also happens when the central bank now has to pay higher interest for banks to keep feeding it dollars.

The problem in that case is that there is no balancing liability that's decreasing alongside gross reserves, so the central bank loses its net worth.

The problem in that case is that there is no balancing liability that's decreasing alongside gross reserves, so the central bank loses its net worth.

21. What the hell, we'll stash the difference in "Other Assets" alongside an overdraft of the government's USD/LBP exchange operations, cause they'll surely buy those liras (for dollars) back.

22. This is why Net Foreign Currency reserves of BdL have evolved the way the graph portrays.

This is a structural problem that can only be fixed if the above measures are avoided, hindering unproductive depletion.

This is a structural problem that can only be fixed if the above measures are avoided, hindering unproductive depletion.

23. Stop (unfresh) deposit dollarization, limit dollarized loans, control the premium on dollar deposits with monetary policy (don't adopt a strict peg), regulate currency substitution...

24. To accumulate positive net reserves; people must demand liras

Measures: try not to interfere with currency market equilibrium, create an incentive for lira use; target domestic productivity, make sure earn our more dollars than we need in liras. The CB will sell liras for $'s

Measures: try not to interfere with currency market equilibrium, create an incentive for lira use; target domestic productivity, make sure earn our more dollars than we need in liras. The CB will sell liras for $'s

25. The above is important to understand for policymakers to implement a rational policy in the future

The above estimates don't even reflect the full dollar gap, it only shows the one at the central bank. There are different creative methods one can use to estimate those.

The above estimates don't even reflect the full dollar gap, it only shows the one at the central bank. There are different creative methods one can use to estimate those.

26. This is not even the beginning of the issue. The problem is that the game above went on for so long, accelerating the same gap on every level of the economy. It got to a point where banks' $ liabilities are so large that there's little hope of paying them back

27. It reached a point where the government is paying them and foreigners with their own money, eventually forcing a default, destroying banks' capital, and in turn the possibility of honoring a depositor.

28. It made paying deposits in liras a worse option that leads to a Venezuela scenario.

It led to the insolvency of the public and private sector.

@nafezouk @lebfinance @AzarsTweets @EHSANI22 @Mohdfaour89 @dgheim @HuseinNourdin @AdibChristian @wael_atallah @LCausality

It led to the insolvency of the public and private sector.

@nafezouk @lebfinance @AzarsTweets @EHSANI22 @Mohdfaour89 @dgheim @HuseinNourdin @AdibChristian @wael_atallah @LCausality

@dan_azzi ❤️

Loading suggestions...